View/Open

Classification of Orofacial Pain

Alain Woda a and Antoon De Laat b,c a Clinical Odontology Research Center, Faculty of Dental Surgery, University of Auvergne, Clermont-

Ferrand, France; b Department of Oral Health Sciences, University of Leuven, Leuven, Belgium; c Department of Dentistry, University Hospitals, Leuven, Belgium

This chapter outlines the main elements to consider in a taxonomic approach to orofacial chronic pain.

The general principles for classification of chronic pain are presented in the introduction to the classification of chronic pain by the International Association for the Study of Pain (IASP) [28]; readers interested in classification are referred to this pragmatic and seminal text. This chapter expresses its main lines of thought, especially in relation to orofacial pain states, and describes some recent developments.

The Goal and Nature of Classification

Terminology

Standardization of terms used for classifying disease and pain entities is the first goal of terminology.

Giving a specific name to a disease is important for patients, clinicians, and researchers. The final step in the diagnostic process is reached when the practitioner formulates the word corresponding to the patient’s disease, illness, or pain condition. The patient finds comfort in belonging to an identified group rather than being left alone as a misunderstood sufferer. Diagnostic naming allows patients to gain insight into their disease, illness, or pain prognosis, helping them feel they have more control over their lives. In many instances, clinicians and researchers come across different terms applied to the same entities. This problem results from the fact that a given entity has been defined differently by non-communicating disciplines. Different wordings may also come from different points of view or from a change in understanding over time as a result of advancing knowledge. Researchers need to know they are referring to the same entity when assimilating information from articles in scientific journals and books or comparing results from clinical research protocols. Thus, it appears that the first requirement for an

adequate term for a given type of pain is to gain acceptance by a majority of professionals in both the clinical and research fields; this majority must be as large as possible.

Defining Diseases and Pain Conditions

The first problem encountered in trying to classify diseases or pain conditions is deciding which entities are to be specified. This question can arise at different levels: for example, how many entities can be identified among all dysfunctional pain conditions in the body, or how many within the head and neck, or how many that are related to temporomandibular disorders (TMDs)? Therefore, one of the first questions is to ask which disease or pain entity should be considered separately from the others and on what basis.

Ideally, any clinical entity should be characterized by its etiology, pathophysiology, clinical presentation, and therapy. In reality, most entities are defined through only three, two, or one of these four elements.

From a pragmatic and clinical point of view, one may state that differences or potential differences in therapeutic response are the most important indicators of separate entities. There are, however, many other possible criteria by which one might construct a classification. Any one of the three other markers— etiology, pathophysiology, and clinical presentation—can be used to build a classification system, and further criteria could be considered such as morphology (organ or tissue) or responses to modern laboratory or imaging techniques.

Basic Properties of a Classification System

Ideally, a classification system should be practical for both clinicians and researchers. Entities should be mutually exclusive, which means that no overlap should be allowed that could lead to a double diagnosis.

The list of entities should be exhaustive, which means that any individual case should find a place in the classification. A single criterion should be used to give a hierarchical order within the classification. Each entity should be described briefly. Any classification system should be considered to be a temporary snapshot that will evolve in line with new scientific knowledge. Clearly, most of these requirements cannot be fulfilled, and any classification system is the result of a large number of compromises.

The enamel, dentin, pulpal, and periapical conditions described within the context of carious diseases provide a good example of a meaningful hierarchical classification based on pathophysiology, identifying entities based on clinical presentation and allowing for adapted therapeutic responses. However, in the area of orofacial pain, and chronic orofacial pain in particular, there is no consensus about the criteria to be used for building a hierarchical classification.

Methods Used for Classification

Although medical taxonomy is a pragmatic affair [28], classification must be based as far as possible on scientific evidence. The scientific methods used to classify pain conditions are outlined below.

Cluster Analysis

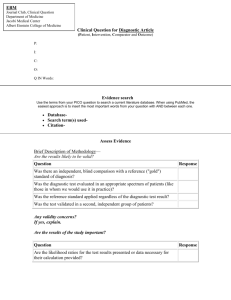

Far removed from “ideal” or “typical” clinical presentations, the clinical reality of orofacial pain is characterized by a broad continuum of sign and symptom combinations with largely overlapping clinical pictures. How many entities or sub-entities must be individualized within the continuum can be determined by cluster analysis. The method as applied to orofacial pain has been described in detail

[48,50]. It has been used in pain studies to define the clustering pattern of patients in several subdivisions for different ill-defined pain entities. [5,6,10–12,22–24,33] and to determine prognosis and treatment recommendations [10–13,16,40,41,45–47], largely on the basis of psychopathological measurements (see references in [7]). Use of cluster analysis in orofacial pain has been mostly limited to the impact of psychological and social/behavioral factors [7,8,14,29,41,44,45]. However, it was applied to the entire group of chronic orofacial pain states in a prospective multicenter study [50] that used signs and symptoms as variables to identify diagnostic groups. The analysis showed three main branches, representing neuralgic, vascular, and dysfunctional groups of orofacial pains. Cluster analysis has recently been used for TMD patients [27]. This study used combined primary and secondary diagnostic subgroups as variables. It identified six groups of diseases with homogeneous clinical profiles: one group of patients presented with myofascial pain; one group of patients had tendonitis, osteoarthritis, or a disk disorder with reduction; a third group had capsulitis or synovitis, and about half of them also had a disk disorder without

reduction as a secondary diagnosis; a fourth group comprised patients with disk disorder without reduction, either as a first diagnosis for about one third, or, for another third, as a secondary diagnosis associated with localized cervical muscle pain. The final two groups comprised patients with poorly identified muscle pain, one with pain in the masticatory muscles, and the other with pain in both the masticatory and cervical muscles. The association of these two studies led to the diagram shown in Fig. 1 in which the two groups with poorly identified local muscle pain are not included because they corresponded to a “wastebasket” taxonomic group [31]. The association of patients with tendonitis or osteoarthritis or disk disorder with reduction in the same cluster and the association of capsulitis/synovitis with disk disorder without reduction exemplify the usefulness of the approach. If these results are confirmed, they may lead to the establishment, on a scientific basis, of sub-entities within the TMD group that would be quite different from what is generally described. The usual descriptions of TMD subgroups are made by associating symptoms involving a single tissue or organ disorder, affecting muscle or disk, for example. The results of cluster analysis shown in Fig. 1 describe a grouping on the basis of the presence of a similar set of symptoms, even if they apparently originate from different organs or tissues.

The cluster analysis approach has two main strengths. First, it obviates any a priori decision. It can therefore be regarded as favoring an evidence-based classification of chronic orofacial pain. Second, it offers a way to classify the different entities hierarchically. It uses signs and symptoms, but it is possible to exclude those related to anatomical locations. Hence, it can be considered to be more closely related to actual pain mechanisms [50] than to classification systems based on tissues or organs.

Some limits of this method must be noted, however. Although the groups identified by cluster analysis are best characterised by the signs and symptoms displayed by the patients in each cluster, these signs and symptoms cannot be considered as diagnostic criteria because their sensitivity and specificity have not been tested. However, diagnostic criteria could be determined for each cluster in a complementary investigation. Another limit of cluster analyses is that large groups of subjects are needed to individualize a disease. Only highly prevalent entities are therefore readily identified. Ideally, several thousand patients

need to be assessed, requiring a complex multicenter, multilingual study. Even then, this method might not identify diseases with very low prevalence. In addition, the representation of certain pain entities may be skewed by patient recruitment, which is conducted in secondary or tertiary care settings. Thus, patients not commonly seen in primary care settings may be selected. Finally, there is some degree of tautology in the approach. Although cluster analysis can identify clusters of patients with similar signs and symptoms, it does not name the identified clusters. To label the clusters, some reference to a pre-existing classification is therefore unavoidable.

Diagnostic Criteria

A given taxonomic entity may represent a group of patients characterized by a large array of signs and symptoms that overlap considerably with neighboring entities. This overlap facilitates the occurrence of multiple and largely redundant entities with slightly different clinical descriptions and totally different terminologies. This lack of a common language and framework means that researchers cannot compare results from different studies and hampers the processes of diagnosis and management in the clinic.

This observation led to the concept of diagnostic criteria, which are necessary for both clinicians and researchers. Diagnostic criteria comprise a small number of signs and symptoms characterizing, as precisely as possible, a definite group of patients. Diagnostic criteria must be “unambiguous, precise and with as little room for interpretation as possible” [19]. Usually, the diagnostic criteria are chosen by a group of experts. Ideally, the chosen set of signs and symptoms constituting the diagnostic criteria, as well as each individual sign or symptom, should be validated against a gold standard [9]. The reliability, sensitivity, and specificity of the diagnostic criteria should be analyzed. Several groups of experts belonging to different scientific societies have proposed diagnostic criteria in the orofacial field

[15,19,28,31]. Examples of thorough efforts to improve the content and validation of these diagnostic criteria have recently been published [1,26,32,35–38,43].

The scientific methodology used to determine these diagnostic criteria makes it possible to draw up consensual definitions that can be adopted worldwide by different groups of researchers. To assure the

reliability of both single tests and the whole set of signs and symptoms characterizing an entity, it is important to gather a large consensus from potential users. This approach has proven to be of great value in forming homogeneous groups of patients for research purposes. These classifications have also proven over time to be invaluable in providing a common worldwide language and framework for clinicians.

Another advantage is that relatively small numbers of subjects can be used to characterize a new entity, which is particularly helpful for infrequent diseases.

There are some limitations, however. Usually, the different groups of patients are defined on the basis of an a priori set of inclusion criteria used to select a group of patients representing a given pain entity. It is from this group that validation of diagnostic criteria can be carried out. The tautological nature of this approach prevents it from being used to identify disease entities. In other words, the diagnostic criteria method does not indicate whether a group of cases belongs to a single disease or lies on a continuum of overlapping cases. In addition, it is difficult to simultaneously satisfy the requirements for research and clinical diagnosis. To create homogeneous groups, the researcher often chooses to reject atypical cases. In contrast, the clinician must manage all cases, even if they are not perfectly typical. These opposing goals have also appeared in the field of TMD. Recently, Steenks and de Wijer [39] contested the utility of the

Research Diagnostic Criteria for TMD (RDC/TMD) [15] in a clinical context because they comprise too limited a set of signs and symptoms. Steenks and de Wijer criticized the lack of cross-correlation between a large set of signs and symptoms as seen in TMD. The problem may lie in the polymorphism of the clinical presentation of TMD with the lack of any objective gold standard. TMD contrasts with entities such as acute irreversible pulpitis, which is easily defined by its clinical presentation and its mandatory therapeutic response. The following diagnostic criteria for acute irreversible pulpitis have been proposed: spontaneous pain located in or around a tooth, pain triggered by a test stimulation applied to the involved tooth, and presence of a route for bacterial contamination of the pulp tissue [49]. As a result, these diagnostic criteria for acute irreversible pulpitis are likely to give few false-positive and false-negative responses. To overcome this difficulty in TMD patients, some experts proposed the concept of multiple

diagnoses [44]. Although offering certain advantages for research, this concept has debatable value for clinical management because the management of an individual patient is not made any easier by the diagnosis of an average of 3.6 sub-entities per patient, as was recently reported [38].

The shortcomings of cluster analysis and diagnostic criteria can be summarized as follows: the cluster analysis method needs very large-scale studies and cannot identify low prevalence entities, while the diagnostic criteria method can characterize some nonexistent diseases. Other considerations are listed in

Table I.

Authority-Based Consensus

An ideal classification should rely on the association of the two methods described above. Existing entities should first be identified through cluster analyses; then, their diagnostic criteria should be defined.

However, the combination of the two methods would still leave many entities with a low prevalence without a description. There is, therefore, an unavoidable need for a more subjective approach in which expert opinion will play the primary role. Over the past two decades, four scientific societies or institutions have sponsored groups of experts and proposed a classification for orofacial pain. As mentioned above, IASP [28] published a classification, organized hierarchically and giving concise descriptions of all types of chronic pain conditions. It includes a description of the main dental, oral, and head pain entities. The International Headache Society (IHS) [19] proposed a classification with diagnostic criteria for all forms of head pain including orofacial pain. The recent third edition of this classification (ICHD-III) devotes two chapters at least in part to orofacial pain conditions [20]. They were written by a committee of experts with either a dental or neurological academic background (the IHS

Classification Committee). In 1996, the American Academy of Orofacial Pain (AAOP) [31] proposed a classification and description of orofacial pain with a chapter devoted to TMD (including diagnostic criteria). It was presented as an addendum to the first edition of the IHS classification. In 1992, a group formed by the U.S. National Institutes of Health [15] proposed a classification with the RDC/TMD.

Shortly thereafter, clinical diagnostic criteria based on the RDC were suggested [44]. A validation and

reliability assessment of the RDC procedures has recently been performed [1,26,32,35–38,43], and new diagnostic criteria for TMD have emerged.

Ontological Approach

Recently, a new approach was proposed on the basis of ontological principles [30]. It started from the observation that confusion is rampant in the terminology. The same term may be used for several meanings or to express different diseases. For example, the word “pain” can be used as a sensation, a symptom, or a disorder, and the term “trigeminal neuralgia” can be used to name a specific entity or to describe pain of neurogenic origin within the trigeminal nerve distribution. This approach relies on the idea that representations, including diagnostic criteria, must be compatible with future scientific advances.

Particular attention was paid to distinguishing various levels of a condition: the reality for the patient, the experience or interpretation by the clinician, and the indirect, administrative documentation of the disease or symptoms. A distinction was also made between the concerns of a single individual and those of all patients in general. These principles were applied to one entity, “atypical odontalgia,” which has been given many different terms. By respecting the above principles, the authors proposed the term “persistent dentoalveolar pain disorder.”

The great interest of this approach relies on the fact that the term is not advocating any etiological or pathophysiological theories that may evolve in the future. There are, however, some difficulties. The extent of the disease may change with time; what was restricted to the dento-alveolar area may merge with similar diseases affecting other areas. In other words, the approach may be applied to a group of patients not forming a real entity if not preceded by a cluster analysis. Actually, “atypical odontalgia” has disappeared from several classification systems to comprise, together with the former term “atypical facial pain,” a new entity termed “persistent idiopathic facial pain” [20,52]. A related difficulty comes from the fact that new terminology cannot be used by a single group of health professionals but must be adopted by the whole dental-medical community.

Taxonomic History of a Newly Accepted Entity: Painful Post-traumatic

Trigeminal Neuropathy

Although it was not planned this way, the history of the recognition of “painful post-traumatic trigeminal neuropathy (PPTTN)” can be considered as an example of the taxonomic approach described above. It has long been known that surgery and some other traumatic events may injure the trigeminal nerve and may provoke symptoms [3]. Many different specialties and procedures may be involved, such as ear-nosethroat surgery with the Caldwell-Luc intervention, orthodontics with orthognathic mandibular advancement surgery, oral and maxillofacial surgery with third molar removal, facial fractures and therapeutic radiation, endodontics with the removal of root canal filling materials, dental implant surgery, and neurology. Several nerves belonging to the mandibular or maxillary divisions of the trigeminal nerve could be involved, but most frequently it is the involvement of the lingual nerve or the inferior alveolar nerve that has a chronological relationship with the onset of the symptoms and the traumatic event, third molar surgery being probably the most common cause [34]. The symptoms are of a neuropathic type, with negative symptoms such as anesthesia or hypoalgesia and/or positive symptoms such as hyperalgesia, dysesthesia, allodynia, and constant burning sensations [4,25,34]. Many different names have been used, including chronic injury-induced orofacial pain, anesthesia dolorosa, post-traumatic neuralgia or neuropathy, secondary trigeminal neuralgia from facial trauma, neuropathic orofacial pain, numb chin syndrome, and peripheral painful traumatic trigeminal neuropathy. This varied terminology indicates that the condition is badly documented, as reflected in the poor description [25] given by the two main classification systems [19,28]. In fact, the condition was not recognized outside the different specialized domains, which seriously hampered successful management of the patient’s problems. Finally, the condition gained full recognition after the recent publication of a series of several well-documented papers

[4,17,21,34], together with the recent meeting of the classification committee of the IHS, which proposed gathering these cases under one diagnosis called “painful post-traumatic trigeminal neuropathy (PPTTN)”

[20].

The recognition of PPTTN can be described as the result of a three-phase approach: identification of the existence of PPTTN, description of PPTTN with diagnostic criteria, and inclusion of PPTTN in a classification system as a result of an authority-based consensus approach.

i) Identification of PPTTN as an entity was suggested by a multicenter study that indicated that the 20 cases of PPTTN found among 245 cases of chronic orofacial pain tended to cluster [50]. This finding is in line with a recent study performed on 328 patients with chronic orofacial pain that indicated that over 12% of the cases involved PPTTN [2]. These studies pointed to a much larger prevalence than had been previously suspected, even if these samples are far from being representative of the general population, being derived from tertiary care centers. Recent publications detail the contribution of the different specialties to the incidence of PPTTN [3,18,25]. ii) The description of diagnostic criteria for PPTTN has improved considerably owing to recently performed work. Quantitative sensory testing associated with electrophysiological exploration improved the delineation of disease characteristics [17,21,34]. In a recent paper, diagnostic criteria initially proposed by the authors were redefined as a returned experience of field-testing [4] (see also Chapter 21).

•

• iii) Inclusion of PPTTN in the IHS classification system was accomplished by a group of experts with either a dental or medical background. PPTTN was inserted under the main heading “chronic painful cranial neuropathies and other facial pains,” under which one subheading was devoted to “painful trigeminal neuropathies.” Under this subheading, PPTTN was listed along with the following conditions: painful trigeminal neuropathy attributed to acute herpes zoster, postherpetic trigeminal neuropathy, painful trigeminal neuropathy attributed to multiple sclerosis plaques, and painful trigeminal neuropathy attributed to space-occupying lesions or to other diseases. Finally, the IHS committee formulated the following diagnostic criteria:

Facial or oral pain fulfilling C and D

History of traumatic event to the trigeminal nerve

• Evidence of causation shown by the following nerve.

•

•

Pain develops within 3–6 months of an identifiable traumatic event to the trigeminal

•

Clinically evident positive (hyperalgesia, allodynia) and/or negative (hypoesthesia, hypoalgesia) signs of trigeminal nerve dysfunction.

Not better accounted for by another ICHD-III diagnosis.

The following comments were added to complete this concise description:

•

Pain duration ranges widely from paroxysmal to constant, and may be mixed. Specifically following radiation-induced postganglionic injury, neuropathy may appear after more than 3 months.

The term “painful” was included in PPTTN because most trigeminal nerve injuries do not result in pain.

Conclusions

Unless it is purely mechanism-based (and consequently might have direct implications on management), classification is secondary. In other words, much more energy and work should be devoted to finding new management techniques, rather than to classifying diseases that we fail to manage properly. Endless debates and struggles about classifications are meaningless in comparison to the patients’ suffering.

Nevertheless, classifications are useful, even for clinicians and patients, but taxonomists should never forget that their constructs are characterized by pragmatism, subjective choices, and temporary statements.

That our certitudes will be challenged is certain.

References

[1] Anderson GC, Gonzalez YM, Ohrbach R, Truelove EL, Sommers E, Look JO,Schiffman EL. The Research Diagnostic

Criteria for Temporomandibular Disorders. VI: Future directions. J Orofac Pain 2010;24:79–88.

[2] Benoliel R, Eliav E, Sharav Y. Classification of chronic orofacial pain: applicability of chronic headache criteria. Oral Surg

Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod 2010;110:729–37.

[3] Benoliel R, Kahn J, Eliav E. Peripheral painful traumatic trigeminal neuropathies. Oral Dis 2012;18:317–32.

[4] Benoliel R, Zadik Y, Eliav E, Sharav Y. Peripheral painful traumatic trigeminal neuropathy: clinical features in 91 cases and proposal of novel diagnostic criteria. J Orofac Pain 2012.26:49–58.

[5] Bierma-Zeinstra SMA, Bohnen AM, Bernsen RMD, Ridderikhoff J, Verhaar JAN, Prins A: Hip problems in older adults: classification by cluster analysis. J Clin Epidemiol 2001;54:1139–45.

[6] Bruehl S, Harden RN, Galer BS, Saltz S, Backonja M, Stanton-Hicks M. Complex regional pain syndrome: are there distinct subtypes and sequential stages of the syndrome? Pain 2002;95:119–24.

[7] Burns JW, Kubilus A, Bruehl S, Harden RN. A fourth empirically derived cluster of chronic pain patients based on the multidimensional pain inventory: evidence for repression within the dysfunctional group. J Consult Clin Psychol

2001;69:663–73.

[8] Butterworth JC, Deardorff WW. Psychometric profiles of craniomandibular pain patients: identifying specific subgroups.

Cranio 1987;5:225–32.

[9] Clark GT, Delcanho RE, Goulet JP. The utility and validity of current diagnostic procedures for defining temporomandibular disorder patients. Adv Dent Res 1993;7:97–112.

[10] Cook AJ, Chastain DC. The classification of patients with chronic pain: age and sex differences. Pain Res Manag

2001;6:142–51.

[11] Coste J, Paolaggi JB, Spira A. Classification of non-specific low back pain. I. Psychological involvement in low-back pain: a clinical, descriptive approach. Spine 1992;17:1028–37.

[12] Coste J, Paolaggi JB, Spira A. Classification of non-specific low back pain. II. Clinical diversity of organic forms. Spine

1992;17:1038–42.

[13] Crook J, Moldofsky H. The clinical course of musculoskeletal pain in empirically derived groupings of injured workers. Pain

1996;67:427–33.

[14] Cyders MA, Burris JL, Carlson CR. Disaggregating the relationship between posttraumatic stress disorder symptom clusters and chronic orofacial pain: implications for the prediction of health outcomes with PTSD symptom clusters. Ann Behav Med

2011;41:1–12.

[15] Dworkin SF, LeResche L. Research Diagnostic Criteria for Temporomandibular Disorders: review, criteria, examinations and specifications, critique. J Craniomandib Pract 1992;6:301–55.

[16] Fanciullo GJ, Hanscom B, Weinstein JN, Chawarski MC, Jamison RN, Baird JC. Cluster analysis classification of SF-36 profiles for patients with spinal pain. Spine 2003;28:2276–82.

[17] Forssell H, Tenovuo O, Silvoniemi P, Jääskeläinen SK. Differences and similarities between atypical facial pain and trigeminal neuropathic pain. Neurology 2007;69:1451–59.

[18] Fried K, Bongenhielm U, Boissonade FM, Robinson PP. Nerve injury-induced pain in the trigeminal system. Neuroscientist

2001;7:155–65.

[19] International Headache Society (Headache Classification Committee). The international classification of headache disorders.

Cephalgia 2004;24:1–136.

[20] International Headache Society. Working group on painful cranial neuropathies and other facial pains of the Headache

Classification Committee: Katsarava Z, et al. (pp. 774–86). In: Olesson et al. The International Classification of Headache

Disorders, 3rd edition (beta version). Cephalalgia 2013;33:629–808.

[21] Jääskeläinen SK, Teerijoki-Oksa T, Forssell H. Neurophysiologic and quantitative sensory testing in the diagnosis of trigeminal neuropathy and neuropathic pain. Pain 2005;117:349–57.

[22] Jason LA, Torres-Harding SR, Carrico AW, Taylor RR. Symptom occurrence in persons with chronic fatigue syndrome. Biol

Psychol 2002;59:15–27.

[23] Klapow JC, Slater MA, Patterson TL, Doctor JN, Atkinson JH, Garfin SR: An empirical evaluation of multidimensional clinical outcome in chronic low back pain patients. Pain 1993;55:107–18.

[24] Langworthy JM, Breen AC. Rationalizing back pain: the development of a classification system through cluster analysis. J

Manipulative Physiol Ther 1997;20:303–10.

[25] Lewis MA, Sankar V, De Laat A, Benoliel R. Management of neuropathic orofacial pain. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol

Oral Radiol Endod. 2007;103(Suppl):S32.e1–24.

[26] Look JO, John MT, Tai F, Huggins KH, Lenton PA, Truelove EL, Ohrbach R,Anderson GC, Shiffman EL. The Research

Diagnostic Criteria for Temporomandibular Disorders. II: Reliability of Axis I diagnoses and selected clinical measures. J

Orofac Pain 2010;24:25–34.

[27] Machado (E Silva) LP, de Macedo Nery MB, de Góis Nery C, Leles CR. Profiling the clinical presentation of diagnostic characteristics of a sample of symptomatic TMD patients. BMC Oral Health 2012;12:26.

[28] Merskey H, Bogduk N. Classification of chronic pain: description of chronic pain syndromes and definitions of pain terms,

2nd ed. Seattle: IASP Press; 1994.

[29] Mongini F, Rota E, Evangelista A, Ciccone G, Milani C, Ugolini A, Ferrero L,Mongini T, Rosato R. Personality profiles and subjective perception of pain in head pain patients. Pain 2009;144:125–9.

[30] Nixdorf DR, Drangsholt MT, Ettlin DA, Gaul C, De Leeuw R, Svensson P, Zakrzewska JM, De Laat A, Ceusters W;

International RDC-TMD Consortium. Classifying orofacial pains: a new proposal of taxonomy based on ontology. J Oral

Rehabil 2012;39:161–9.

[31] Okeson JP. Orofacial pain: guidelines for assessment, classification, and management. Chicago: Quintessence; 1996.

[32] Ohrbach R, Turner JA, Sherman JJ, Mancl LA, Truelove EL, Schiffman EL, Dworkin SF. The research diagnostic criteria for temporomandibular disorders. IV: Evaluation of psychometric properties of the Axis II measures. J Orofac Pain

2010;24:48–62.

[33] Ragnarsson G, Bodemar G: Division of the irritable bowel syndrome into subgroups on the basis of daily recorded symptoms in two outpatient samples. Scand J Gastroenterol 1999;34:993–1000.

[34] Renton T, Yilmaz Z. Profiling of patients presenting with posttraumatic neuropathy of the trigeminal nerve. J Orofac Pain

2011;25:333–44.

[35] Schiffman E, Ohrbach R, List T, Anderson G, Jensen R, John MT, Nixdorf D, Goulet JP, Kang W, Truelove E, Clavel A,

Fricton J, Look J. Diagnostic criteria for headache attributed to temporomandibular disorders. Cephalalgia 2012;32:683–92.

[36] Schiffman EL, Ohrbach R, Truelove EL, Tai F, Anderson GC, Pan W, Gonzalez YM, John MT, Sommers E, List T, Velly

AM, Kang W, Look JO. The Research Diagnostic Criteria for Temporomandibular Disorders. V: Methods used to establish and validate revised Axis I diagnostic algorithms. J Orofac Pain 2010;24:63–78.

[37] Schiffman E, Ohrbach R, Truelove E, Look J, Anderson G, Goulet JP et al., Diagnostic criteria for temporomandibular disorders (DC/TMD) for clinical and research applications: recommendations of the International RDC/TMD Consortium

Network and Orofacial Pain Special Interest Group. J Orofac Pain 2014; in press.

[38] Schiffman EL, Truelove EL, Ohrbach R, Anderson GC, John MT, List T, Look JO. The The Research Diagnostic Criteria for

Temporomandibular Disorders. I: Overview and methodology for assessment of validity. J Orofac Pain 2010;24:7–24.

[39] Steenks MH, de Wijer A. Validity of the Research Diagnostic Criteria for Temporomandibular Disorders Axis I in clinical and research settings. J Orofac Pain 2009;23:9–16.

[40] Stiefel FC, de Jonge P, Huyse FJ, Slaets JP, Guex P, Lyons JS et al. INTERMED: an assessment and classification system for case complexity. Results in patients with low back pain. Spine 1999;24:378–85.

[41] Strong J, Large RG, Ashton R, Stewart A. A New Zealand replication of the IPAM clustering model for low back patients.

Clin J Pain 1995;11:296–306.

[42] Suvinen TI, Reade PC, Hanes KR, Kononen M, Kemppainen P. Temporomandibular disorder subtypes according to selfreported physical and psychosocial variables in female patients: a re-evaluation. J Oral Rehabil 2005;32:166–73.

[43] Truelove E, Pan W, Look JO, Mancl LA, Ohrbach RK, Velly AM, Huggins KH, Lenton P, Shiffman EL. The Research

Diagnostic Criteria for Temporomandibular Disorders. III: Validity of Axis I diagnoses. J Orofac Pain 2010;24:35–47.

[44] Truelove EL, Sommers EE, LeResche L, Dworkin SF, Von Korff M. Clinical diagnostic criteria for TMD. New classification permits multiple diagnoses. J Am Dent Assoc 1992;123:47–54.

[45] Turk DC, Rudy TE. Towards an empirically derived taxonomy of chronic pain patients: integration of psychological assessment data. J Consult Clin Psychol 1988;56:233–8.

[46] Turk DC, Rudy TE. The robustness of an empirically derived taxonomy of chronic pain patients. Pain 1990;43:27–35.

[47] Weiner DK, Rudy TE, Gaur S. Are all older adults with persistent pain created equal? Preliminary evidence for a multiaxial taxonomy. Pain Res Manag 2001;6:133–41.

[48] Woda A. A rationale for the classification of orofacial pain. In: Türp JC, Sommer C, Hugger A, editors. The puzzle of orofacial pain. Pain and headache. Basel: Karger; 2007. p. 209–22.

[49] Woda A, Doméjean-Orliaguet S, Faulks D, Augusto F, Bourdeau L, Deluzarche S, Gentilucci L, Gondlach C, Renon C,

Ricard O, Santoni B, Sugnaux N, Roux D. Réflexions sur les critères diagnostiques des maladies pulpaires et parodontales d’origine pulpaire. Inf Dent 1999;43:3473–8.

[50] Woda A, Tubert-Jeannin S, Bouhassira D, Attal N, Fleiter B, Goulet JP, Gremeau-Richard C, Navez ML, Picard P, Pionchon

P, Albuisson E. Towards a new taxonomy of idiopathic orofacial pain. Pain 2005;116:396–406.

[51] Woolf CJ, Bennett GJ, Doherty M, Dubner R, Kidd B, Koltzenburg M, Lipton R, Loeser JD, Payne R, Torebjork E. Towards a mechanism-based classification of pain? Pain 1998;77:227–9.

[52] Zakrzewska JM, Woda A, Stohler CS, Vickers R. Classification, diagnosis and outcome measures in patients with orofacial pain. In: Flor H, Kalso E, Dostrovsky JO, editors. Proceedings of the 11th World Congress on Pain. Seattle: IASP Press;

2006. p. 745–54.

Correspondence to: Alain Woda, DDS, PhD, Centre Recherche Odontologie Clinique (CROC), Faculté chirurgie dentaire, Université d’Auvergne, 11 Bld. Charles de Gaulle, 63000, Clermont-Ferrand, France.

(Email:alain.wodadamail.fr)

Fig. 1.

Diagram based on the results of two studies that used cluster analysis [27,50].

TMD, temporomandibular disorder.