cmv infection rates post renal transplant

advertisement

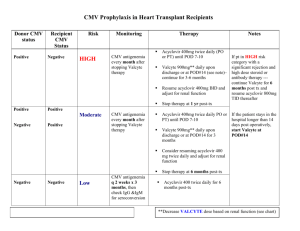

P242 CMV prophylaxis in renal transplant patients within the Northern region during 2011 and 2012. R. Davison1,3, F. Dowen1, J. Palfrey2,, E. Montgomery4, F. Dallas 4, D. Reaich2, M. Valappil1 & K. Jones1. 1 Freeman Hospital, Newcastle upon Tyne, 2 James Cook University Hospital, Middlesbrough, 3 Sunderland Royal Hospital, Sunderland, 4 Cumberland Infirmary, Carlisle. BACKGROUND: Cytomegalovirus (CMV) related disease is a significant cause of morbidity and mortality following renal transplantation. Our CMV protocol recommends prophylaxis with Valganciclovir for all donor positive / recipient negative (D+/R-) patients or any donor positive or recipient positive combination if T-cell depleting agents are used. This should be commenced within 10 days of transplantation and continued for 100 days except in high-risk patients (e.g. D+/R- receiving Campath ®) who continue prophylaxis for 200 days. AIM: To document the incidence of CMV viraemia and disease, along with protocol adherence in renal transplant recipients from 01/01/11 to 31/12/12. To compare protocol adherence to previous data collected between 2005-2010. METHODS: All patients who received a kidney or simultaneous pancreas kidney transplant (SPK) between 01/01/11–31/12/12 were included in our study. Data was collected from all patients who had transplant follow up in the 4 renal units, in the North East and Cumbria. Retrospective data was collected from patient notes and pathology systems. We assessed donor/recipient status, prophylaxis prescription (drug, dose and duration) and evidence of CMV viraemia or disease, treatment and complications. RESULTS: Between 01/01/2011 – 31/12/2012 a total of 214 patients received a kidney or SPK transplant. Based on our protocol 59 (27.6%) met the criteria for CMV prophylaxis of whom 52 (88%) received Valganciclovir. The dose was correct in 96.6% of these patients and the duration correct in 78%. Of those who were prescribed an incorrect duration, 60% had the prophylaxis continued on longer than the protocol recommendations. There were 22 (10.3%) cases of CMV (15 with CMV disease and 7 with viraemia), 11 of whom were high risk according to our protocol. All 22 of these patients received prophylaxis however one patient had too low a dose and in two patients the prophylaxis was discontinued too early. In patients with CMV infection there was a low incidence (1 person (4.5%)) of new onset diabetes after transplant (NODAT). There were no cases of acute rejection (AR). Of the 32 patients who received T-cell depleting agents (Campath®), one had low level viraemia detected. Of the 15 cases of CMV disease, 14 were successfully treated and one patient died as a result of CMV pneumonitis. When compared to our previous data collected between 2005-2010, there was a lower incidence of CMV infection (10.3% compared to 12.5%), a decrease in acute rejection in those with CMV infection (18.8% down to 0%) and a fall in NODAT following CMV infection from 11.4% to 4.5%. CONCLUSION: Adherence to our CMV prophylaxis protocol since 2010 has improved and we have noted a small reduction in CMV infection. However we are still only correctly prescribing prophylaxis appropriately in 78% of patients. Documenting reasons for deviation from the protocol is incomplete and it is not uncommon for us to continue prophylaxis longer then protocol recommendations.