cmv infection rates post renal transplant

advertisement

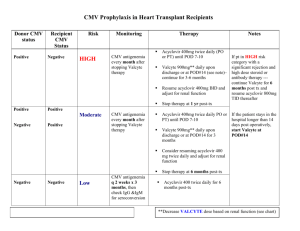

O13 CMV INFECTION RATES POST RENAL TRANSPLANT - SINGLE CENTRE EXPERIENCE Bavakunji, R, Rathod, J, Knight, A, Evans, L, Byrne, C Renal Transplant Unit, Nottingham University Hospitals NHS Trust, City Hospital BACKGROUND: Post transplant cytomegalovirus (CMV) disease is a major cause of morbidity and mortality. Studies have shown that 200 days of prophylactic Valganciclovir is more effective than 100 days in high risk group CMV Donor positive and recipient negative (D+/R–) recipients (1). Our unit protocol is to give CMV prophylaxis with oral Valganciclovir for 3 months for all CMV D+/R– recipients or if Anti-lymphocyte antibody therapy (ATG) has been given for treatment of biopsy proven acute rejection (BPAR) unless both donor and recipient are CMV IgG negative. AIM: To study overall incidence, severity and outcome of CMV infection after 100 days of prophylactic Valganciclovir. We also evaluated if extending prophylaxis to 200 days in our recipients was cost effective or likely to be clinically beneficial. METHODS: All alone kidney transplant recipients were included in the analysis. Retrospective data were collected from the renal database PROTON, Nottingham information system lab reporting programme (Notis), and case notes review. Seven recipients were excluded due to non-availability of case notes and two had kidney pancreas transplants performed elsewhere. Incident recipients with infections between 1.1.2006 to 30.6.2011 who had late onset disease (>100 days) were analysed. RESULTS: There were 290 lone-kidney transplants performed in 285 recipients during the study period. Fifty six (19%) recipients were high risk CMV D+/R–, of these 5 transplants had primary non function. All appropriate recipients received prophylaxis. Forty six recipients (16%) were identified with CMV infection, regardless of sero-status. The mean age was 46 years (SD±14). Nineteen of the 46 (41.3%) had late onset CMV infection. Of these 11 (23.17%) recipients in this group were high risk (CMV D+/R–). In the late onset high risk group (11 recipients) there were two episodes of BPAR, both preceding CMV infection by several months. All except two, patients were treated with Valganciclovir, three required additional intravenous Ganciclovir and one was treated with foscarnet due to CMV induced leucopenia. The median duration of treatment was 51 days (range 122 -13 days). Two recipients had CMV reactivation requiring further extended treatment courses for a median period of 84 days. The average cost of the out-patient treatment with Valganciclovir was £2200.00. One patient was hospitalised due to gastrointestinal haemorrhage. In our high risk late onset cohort, the main symptom in recipients with CMV infection was diarrhoea (33.3%), followed by fever and flu like (43%) symptoms. Four recipients had abnormal liver function tests. Although one patient had presumed tissue invasive disease this was not biopsy proven. There was one graft failure unrelated to CMV infection or immunosuppression changes and there were no deaths directly related to CMV infection. Renal function remained unchanged after treatment of CMV for up to 3 yrs. None of the recipients had CMV infection related rejection. If we were to extend our prophylaxis by a further 100 days for the 56 high risk recipients our estimated additional costs would be £ 121,072, which is considerably more than the costs of treating CMV infection as it arises. CONCLUSION: In our unit late onset CMV does not seem to cause any significant mortality or rejection episodes. Pre-emptive therapy along with prompt immunosuppression reduction, as opposed to longer prophylaxis, is cost effective with lower risk of medication induced side effects in our population. We suggest all transplant units should analyse their own incidence and severity to justify 200 days prophylaxis. References 1. Humar A et al. the efficacy and safety of 200 days cytomegalovirus prophylaxis in high-risk kidney transplant recipients. Am J Transplant 2010; 10:1228-1237