Aromatherapy Research Article September 2014 Echinacea

advertisement

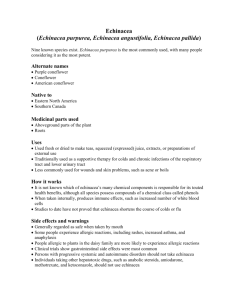

Aromatherapy Research Article September 2014 Echinacea Echinacea, also known as coneflower, is a genus of hardy, herbaceous perennial plants native to North America. The genus contains three species that are used for their medicinal properties, known as E. purpurea (purple coneflower) E. palladia (pale coneflower) and E. angustifolia (narrow-leaf purple coneflower) (Barnes et al., 2005). These species have been used in herbal medicine for centuries, mainly for the treatment of respiratory tract infections, but also for treating syphilis, snakebites and septicaemia (Percival, 2000; Barnes et al., 2005). However, the plant has remained popular, and is one of the most popular herbal preparations sold in Germany and the USA. It is sold commercially in variety of forms, such as in capsules and tinctures (Barnes et al., 2005). In aromatherapy, Echinacea comes in the form of an oil that is prepared by maceration in sunflower oil, which is used either alone due to its intrinsic benefits or as a carrier for essential oils. Therapeutic Properties Antiviral Various species and extracts of Echinacea have been studied for antiviral activity in vitro. In one in vitro study, it was concluded that an aqueous extract of E. purpurea had potent antiviral activity against influenza virus and herpes simplex virus, which was enhanced by exposure to light; however this extract was not effective against rhinovirus, a virus implicated in the common cold (Hudson et al., 2005). Another study that found incubating mouse fibroblasts cells with a juice of Echinacea or methanolic or aqueous extracts of Echinacea resulted in the fibroblasts resisting infection by influenza and herpes viruses for 24 hours (Barnes et al., 2005). These studies suggest that Echinacea could be useful in remedies against these infections. However, a human clinical trial found no significant effect of Echinacea extracts on the recurrence and severity of genital herpes recurrences (Vonau, 2001). In contrast, a mouse study has investigated the effect of Echinacea against the clinical outcome of influenza. It was found to decrease weight loss when infected compared to untreated mice, despite the counts of virus in the lungs not being statistically different. The levels of proinflammatory cytokines in the blood and lungs was significantly lower in the Echinaceatreated mice, suggesting that the improved outcome form influenza infection is due to an immunomodulating activity and not a direct antiviral activity (Fusco et al., 2010). In relation to clinical trials investigating the effect of Echinacea against common colds, a meta-analysis of 3 articles that the likelihood of experiencing symptoms of a common cold were 55% higher with placebo than with Echinacea extracts (Schoop et al., 2006). Conclusion: there is some evidence to suggest that Echinacea possesses antiviral activity and may thus be useful in preventing and improving the outcome of viral infections; however this may be due to modulation of the immune system and not a direct antimicrobial effect. There is a lot of conflicting data on the subject, thus well designed human clinical trials against standardised Echinacea extracts would provide a more detailed insight into their clinical efficacy. Immunomodulation As mentioned previously Echinacea is reported to affect the immune system. In fact, Echinacea is the most popular herbal immune stimulant in North America and Europe (Oomahet al., 2006). The effect of Echinacea on the immune system has been studied extensively both in vitro and in vivo, with an overall consensus that Echinacea extracts act as immune stimulants, but tends to be referred to as immunomodulatory, as widespread immune stimulation can be harmful (Barrett, 2003). Echinacea has been investigated in both in vitro and in vivo against macrophages, a type of white blood cell involved in the immediate immune response to infection and injury by engulfing debris such as microbes, and recruit other cells by producing proinflammatory cytokines. It was found that both mouse and human macrophages had greater phagocytic (engulfing) activity and increased their production of the cytokines IL-1,IL-10 and TNF-α when treated with Echinacea compared to controls (Barnes et al., 2005). Furthermore, samples of peripheral white blood cells from healthy humans, AIDS patients and ME patients (who both have depressed immune systems) treated with Echinacea revealed an increase in natural killer cell function. This is supported by a mouse study performed in vivo in normal, leukemic and aging mice (who have depressed immune systems), which also found an increase in natural killer cell function (Barnes et al., 2005). As the name suggests, natural killer cells are important in immune responses as they are primed to kill immediately and don’t need activation by other cells. They specialise in killing virally-infected cells, preventing spread to the surrounding tissues. This is therefore a potential mechanism of Echinacea’s reported use in viral infections. Antiinflammatory The polyunsaturated alkamides from E. angustifolia were found to inhibit cyclooxygenase and 5-lipoxygenase activity, key processes involved in inflammation, suggesting an anti-inflammatory effect. Animal studies have also shown an antiinflammatory effect from topical application of the polysaccharide fraction derived from E. angustifolia root. Both carrageenan-induced rat paw oedema and the inflammation associated with the croton oil ear test were reduced significantly in animals treated topically with Echinacea (Percival, 2000). Wound Healing One study used experimental skin abrasions in rats to demonstrate the antiinflammatory and wound healing properties of a topical preparation of Echinacea as well as one of its components echinacoside. Wound healing was found to be greater than controls after 48 and 72 hours, although no statistical analysis was performed. The polysaccharide fraction of Echinacea is thought to be responsible for its wound healing properties, due to inhibiton of hyaluronidase, an enzyme that breaks down hyaluronic acid, an important substance in wound healing due to its role in forming the extracellular matrix. Echinacoside is also thought to protect collagen from free radicalinduced damage and degredation, as concluded from an in vitro model of skin damage caused by UV light exposure (Barnes et al., 2005). References BARNES, J. et al. (2005) Echinacea species (Echinacea angustifolia (DC.) Hell., Echinacea pallida (Nutt.) Nutt., Echinacea purpurea (L.) Moench): A Review of their Chemistry, Pharmacology and Clinical Properties. Journal of Pharmacy and Pharmacology, 57 (8), pp. 929-954. BARRETT, B. (2003) Medicinal Properties of Echinacea: A Critical Review. Phytomedicine, 10 pp. 66-86. FUSCO, D. et al. (2010) Echinacea purpurea Aerial Extract Alters Course of Influenza Infection in Mice. Vaccine, 28 (23), pp. 3956-3962. HUDSON, J. et al. (2005) Characterisation of Antiviral Activities in Echinacea Root Preparations. Pharmaceutical Biology, 43 (9), pp. 790-796. OOMAH, B.D. et al. (2006) Characteristics of Echinacea Seed Oil. Food Chemistry, 96 (2), pp. 304-312. PERCIVAL, S.S. (2000) Use of Echinacea in Medicine. Biochemical Pharmacology, 60 (2), pp. 155-158. SCHOOP, R. et al. (2006) Echinacea in the prevention of induced rhinovirus colds: A meta-analysis. Clinical Therapeutics, 28 (2), pp. 174-183. Vonau, B. (2001) Does the extract of the plant Echinacea purpurea influence the clinical course of recurrent genital herpes? International Journal of STD and AIDS, 12 (3), pp.154-158.