Bob Marley Ancient Philosophy November 18, 2012 Fatalism and

advertisement

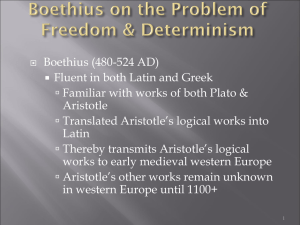

Bob Marley Ancient Philosophy November 18, 2012 Fatalism and the Future The concept of fatalism is one which has been discussed for thousands of years. Philosophers have argued various theories as to why and how things are determined. Some have argued God or gods play a role through some sort of divine power, or things are one way or the other simply because, or self-determination, or the results of things are determined by logical truths, which is what Aristotle argues in his famous chapter 9 of De Interpretatione, which I will refer to as DI9 throughout this paper. In Aristotle’s DI9, he gives the reader an example of a sea battle and states that if there will be a sea battle tomorrow then it is true that there will be one. If this is true or false, then it is necessary that the sea battle will or will not happen tomorrow. Philosophers who have studied fatalism have varying opinions on Aristotle’s argument here and throughout DI9. McKim discusses in Fatalism and the Future: Aristotle’s Way Out, how exactly Aristotle’s argument has some ground and support for the Non-Standard Interpretation and the Standard-Interpretations of fatalism. I will discuss McKim’s opinion throughout this paper, and I will also attempt to defend his arguments as valid interpretations of all the various theories of fatalism in reference to SI, NSI, and Aristotle’s arguments as well as add my own argument where I feel McKim’s analysis falls short. McKim begins his piece by stating that there are four distinct questions that have been disputed regarding Aristotle’s DI9. They are as follows: “(i) what Aristotle’s own positive solution amounts to, (ii) whether the position he adopts is tenable, (iii) whether his distinctions actually 1 refute fatalism, and (iv) whether fatalist arguments presented in DI9 can be refuted,” (80). McKim goes on to point out there he will interpret Aristotle’s view based also on the SI and NSI arguments, but only parts of them which are applicable to understanding Aristotle’s argument in question. A SI fatalist view would agree that if it is true that a sea battle will or will not happen tomorrow, then it is necessary that it is true that what happens or does not happen occurs. Most fatalist philosophers accept this view. However, an issue here with the SI view of fatalism is that it relies very heavily on the principle of bivalence, which is that the outcome is either true or false and that there are no maybes or in-between answers, which I will discuss more in depth later on. In contrast to the SI, there is the NSI view, “which aims to create an interpretation of DI9 which is viable in its own right, and one which at the same time undercuts the plausibility of the SI,” (83). The argument here does not restrict any logical principles, but rather it attempts to say that the common fatalist argument tends to lead to confusion and misunderstanding. The NSI proponents do however feel that (iii) and (iv) do allow for sufficient information to show that fatalism is spurious. McKim then goes on to say that the modal restrictions that NSI impose do not give us enough information to invalidate the fatalist argument which is being presented. He also feels that the semantic qualifications that are deemed necessary in the SI are truthfully not the ultimate deciding factor in fatalism. The fact of the matter is that, in relation to an overall experience in reference to events that may be true or false, there is potential to go in either direction. And this potential is meant towards what will happen in the future. One of the shortcomings of Aristotle’s DI9 is that, in it, he believes that other philosophers misunderstand fatalism, but he fails to defend it other than saying what he says is the true position. McKim points out however that “the complexity of his 2 own position (Aristotle) is a direct function of the complexity of the fatalist position itself,” (86). He then goes on to remind us that no one point of the SI or NSI is responsible for explaining the fatalist debate properly. The main point that McKim makes here is that to understand the fatalist argument, we must first comprehend the distinction between truth and decidability. For McKim the wording of the arguments and their premises allows for an interpretation that views claims as truths, and these same premises also allow room for propositions being based on decidability. McKim goes on to describe what he meant by claims being viewed as truths. Here, he uses the example of how it is true to say a said thing is white; it must not necessarily be white. And it still remains true when you reverse the predicates. “Claims about truth mean that the premises become propositions which act as predicates of truth and necessity,” (88). The argument here is that necessity is something based on existence of non-existence. The argument continues to go on to say that events are only necessary when they have occurred, which leaves us wondering what does a sense of time or temporal reasoning play in DI9? Historically, Aristotle’s arguments when using the word necessary are meant to stand for things that will always be true in his eyes. Whereas the word possible connotes things as being sometimes true. If the DI9 argument was saying that a sea battle might occur tomorrow – that would become an argument of possibility and not necessity, which would disregard the problematic issue of truth value. Because the argument is viewed as necessity, we are left to struggle with what it means for it always being true whether the action occurs or not. If we accept the conclusion of DI9, we are left to believe that all events are determined. However, 3 when we actually consider the argument based on temporal necessity, McKim argues that we are left with the conclusion that provides no argument to support determinism. In part IV, McKim goes on to differeniate between how Argument I is an argument based on propositions of decidability and is therefore not one that argues for claims of truth. Argument II however uses the words impossible and possible, which as an example allows for determinism. His argument goes on to point out that was will happen, what has happened. These minor changes in verb tenses shows us the examples of the past, present, and future. What is happening in all three instances assumes that the claims are true based on assumptions that from a first person point of view that we can know ultimately that ‘S is P.’ McKim argues that because we can say that something is now a certain way (present tense), this will give the statement validity and truth value and proves that whatever was said earlier to the now, now is given a sense of truth to it, because it has proven the past to have existed at one point and time. However, what is said earlier does not necessarily imply that “S will be P,” but rather the future can only be determined based on the now and not the present. Thus, a contingent proposition cannot be said to be determinate if it is to be true or false is the same said event has either taken place or has failed to ever take place, (99). For me, I would argue that this previous argument fails to fully explain how the pastpresent-future relations even exist in relation to something being true or not. It examines that the truth of something occurs step by step, but I feel that something cannot be true until after it happens, which would eliminate the truth value of the future altogether. How can one perceive the future, something that no one can determine? A person can plan to do one thing, but the 4 end result may not be what was normally planned. Sure, it could be true that a sea battle takes place, but one could argue that is it true or not true that Side A will defeat Side B in the sea battle tomorrow or later today, time is irrelevant. But could not the end result of a battle be a truce? The acceptance of bivalence here allows for the argument to be true, but in reality I would argue that there are always more than true or false answers to any and all questions in life. Things are not just black and white – not even mathematical functions and equations, because every problem has various ways of being solved; not to mention there are exceptions to every rule in math/chemistry/physics, which complicates things much more and does not allow for things to be simply true or false. McKim goes on to attempt to compare both his SI and NSI explanations along with what he feels is the proper analysis of DI9. The SI view “maintains that Aristotle’s solution is to modify the Principle of Excluded Middle,” (101). The PEM is an argument that states that every case must either confirm or negate. This logic theory also assumes that contradictions between the two exist. Again, I find this PEM problematic, along with the idea of bivalence, which is a theory where things are either true or false. A modified version of PEM sounds like it might lead to more open explanations of why something is true or false, and this would result in arguments being much more complex rather than true or false. I would argue that if PEM is modified too much, as Aristotle seems to argue for, then there an in-between view or stance on a said event becomes much more likely and possible. If one looks into Aristotle’s argument however, they show that he feels fatalist arguments are invalid, and they therefore require the PEM. McKim goes on to say that the SI should be rejected in part, because is neither provides “a fully cogent rendering of the text of an account of Aristotle’s problem and the strategy that he adopts in 5 dealing with it,” (103). McKim continues and states that “…it could be claimed that correspondence is a necessary condition for our being entitled to call a proposition true.” Correspondence here can mean two distinctly different things. One, it could be used to explain what we mean for a proposition being true. It could also mean that it becomes a necessary component in us being able to determine is a proposition is true or not. The former argument views truth as one of semantic explanation. The latter view of correspondence can only be a useful argument if one assumes that we have the ability to see something as true based on evidence of a truth-value may become as such through decidability and verifiability. This leads us to a notion of actual truths and to better under this argument we must look into Aristotle’s concept and definition of truths. Aristotle views truth much differently than most philosophers of his time. For him, truth should not and cannot be applied to propositions, but rather, for him, truth is applied to sentences which are token-reflexive. This means in other words that all of his arguments implicitly and explicitly use the word “now.” With the use of the word now and the present tense, this tends to lead us to understand that everything becomes true or false and an event’s truth value is decided at that same moment – the present. Based on these arguments, it is logical to strongly assume that Aristotle probably tended to feel that his arguments were based on singular propositions and thus were all viewed as actually true or actually false (104). As we can now see through previous examples throughout McKim’s work, Aristotle has accepted the argument that “the fatalistic consequences of his modal as indicative have the need to reconsider the semantically assumptions implicit in the paradigm itself,” (105). 6 From a NSI perspective, there is no need to assume that Aristotle’s argument was coerced in somewhat to limit the application of PEM in his DI9. But the problem that exists with NSI is that it attempts “to construe Aristotle’s basic insight in DI9 in terms of necessary truths and it obscures the reality that it is de re, not de dicto necessity which figures so conspicuously in the arguments for fatalism,” (107). Another issue that is present in Argument I and II are the ambiguities, because they lead for too much interpretation and misunderstanding. Of course, I find this argument by McKim rather weak, in a sense that all arguments have room for interpretation and if we accept a bivalence view, Aristotle’s view does make sense. What we need to do to accept Aristotle’s view is to remember that the ambiguity of a consequent clause stems for its necessity to be expressed as unconditional or temporal. The distinction here leaves us with “a sense in which the inference holds for any position, there si no sense that implies determinism is true, (111). So what does McKim leave us with as Aristotle’s interpretation of DI9? Fatalism is in fact an untenable doctrine. However, the assumptions made to prove that its validity are based on ambiguities rather than falsehoods. 7 Works Cited: Fatalism and the Future: Aristotle's Way Out. Vaughn R. McKim. The Review of Metaphysics , Vol. 25, No. 1 (Sep., 1971), pp. 80-111. 8