Media Release

Mirjam Guesgen

+64 6 951 7298

+64 21 740 414

M.J.Guesgen@massey.ac.nz news.massey.ac.nz

Wednesday, January 27, 2016

Scientists ‘tickled pink’ over carotenoid discovery

Embargoed until 12noon (NZT), Thursday, January 28, 2016

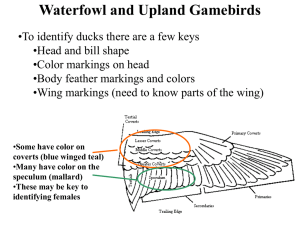

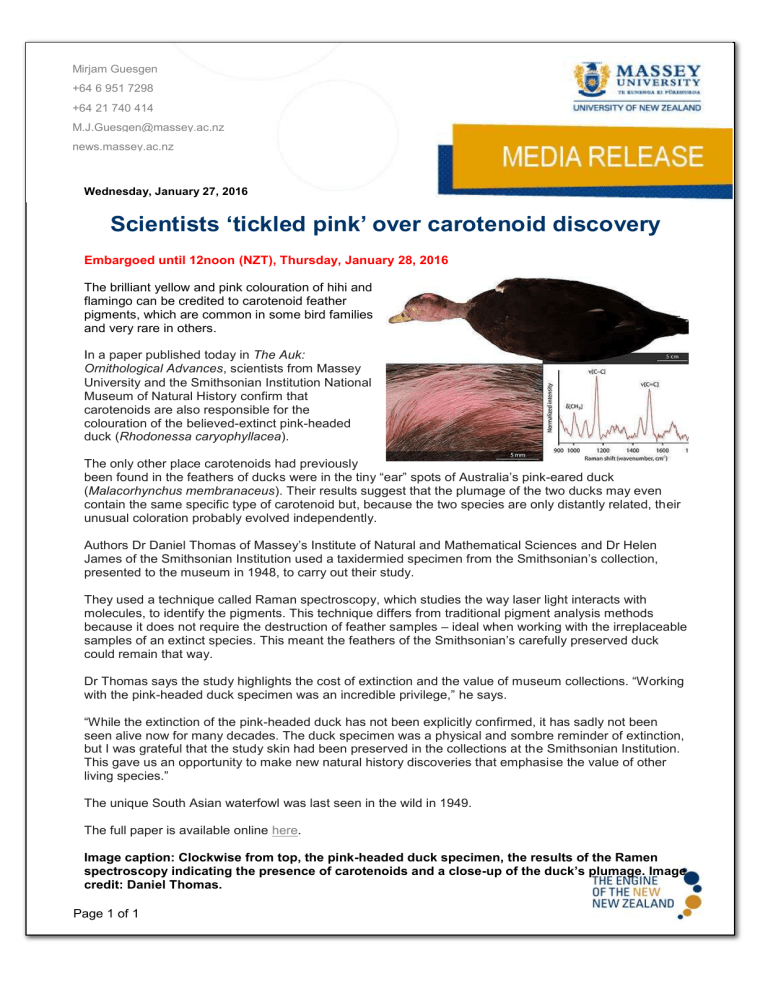

The brilliant yellow and pink colouration of hihi and flamingo can be credited to carotenoid feather pigments, which are common in some bird families and very rare in others.

I n a paper published today in The Auk:

Ornithological Advances , scientists from Massey

University and the Smithsonian Institution National

Museum of Natural History confirm that carotenoids are also responsible for the colouration of the believed-extinct pink-headed duck ( Rhodonessa caryophyllacea ).

The only other place carotenoids had previously been found in the feathers of ducks were in the t iny “ear” spots of Australia’s pink-eared duck

( Malacorhynchus membranaceus ). Their results suggest that the plumage of the two ducks may even contain the same specific type of carotenoid but, because the two species are only distantly related, their unusual coloration probably evolved independently.

Authors Dr Daniel Thomas of Massey’s Institute of Natural and Mathematical Sciences and Dr Helen

James of the Smithsonian Institution used a taxidermied specimen from the Smithsonian’s collection, presented to the museum in 1948, to carry out their study.

They used a technique called Raman spectroscopy, which studies the way laser light interacts with molecules, to identify the pigments. This technique differs from traditional pigment analysis methods because it does not require the destruction of feather samples – ideal when working with the irreplaceable samples of an extinct species. This meant the feathers of the Smithso nian’s carefully preserved duck could remain that way.

Dr Thomas says the study highlights the cost of extinction and the value of museum collections. “Working with the pink-headed d uck specimen was an incredible privilege,” he says.

“While the extinction of the pink-headed duck has not been explicitly confirmed, it has sadly not been seen alive now for many decades. The duck specimen was a physical and sombre reminder of extinction, but I was grateful that the study skin had been preserved in the collections at the Smithsonian Institution.

This gave us an opportunity to make new natural history discoveries that emphasise the value of other living species.”

The unique South Asian waterfowl was last seen in the wild in 1949.

The full paper is available online here .

Image caption: Clockwise from top, the pink-headed duck specimen, the results of the Ramen spectroscopy indicating the presence of carotenoids and a closeup of the duck’s plumage. Image credit: Daniel Thomas.

Page 1 of 1