Interviewer * italic text

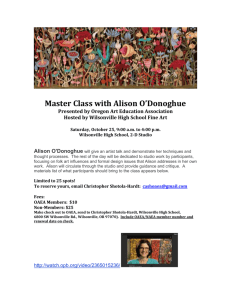

advertisement

Interviewed c.1978 by Janet Druker, then a PhD student at the University of Warwick Interview – John Leonard Transcribed by Alison McPherson, alison.mcpherson@premiertyping.com, www.premiertyping.com Interviewer – italic text Interviewee – normal text Transcription problem (inaudible/unclear) – text within [] is my guess of what was said in the context of the conversation or “?”. One very obvious thing which I’m trying to do to start off with, and that is really to ask people a bit about their background, so that I know something about, if you like, people who were active in the building trade unions, and I wondered if you could tell me, first of all, your full name, your date of birth, and something about your parents, your family background… Well, my full name is John Leonard. Date of birth is the 25th of July 1909. My home of course was in Paisley, in Scotland, the West of Scotland. I served my apprenticeship as a bricklayer, completing my apprenticeship in 1924. I was fairly active in the branch of the then AUBTW, although the AUBTW had only been formed as a consequence of amalgamations in 1921, and it was formerly known as the OBS, the Operative Bricklayers’ Society. I was active in the branch, eh, for quite a considerable time, and, in 1939, I was elected, because of the electoral procedure of the union, I was elected the Additional District Organiser for the Glasgow District. I subsequently became the District Organiser, having succeeded an officer who’d died while in office. I served in that capacity until 1948, when I was elected the Divisional Officer of the Union, responsible for what was then known as our Number 10 Division, covering Scotland and Northern Ireland. So you worked full-time for the union? I was full-time from 1939, full-time. As I say, I occupied the post of Divisional Organiser until 1951, when I was elected the first Assistant General Secretary of the Union, and of course I had to come south in January of ’52. But in 1945, whilst an officer of the Union, I did get the permission of the then Executive to stand for the local authority, the Paisley Town Council, and I served on that Council until December of ’51, when I had to resign my seat on being appointed an AGS, and came south here, to be domiciled here. I acted as Assistant General Secretary from 1952 until 1962, when the then President of the Union was elected General Secretary of the National Federation of Building Trade Operatives, and I subsequently stood for the post and was elected in 1962. I remained in that position right up until 1971, when the transfer to the ASW became effective. So, that’s the background as far as I’m concerned. Yes. Can you tell me a little bit about, going back to the ‘30s and so on, were you active when you were still working at the trade, within the Federation, say at site level, as a Federation steward or something like this? Well, I was active insofar as I was attending the local Federation branches. As you know, the National Federation of Building Trade Operatives had regions – they called them regions, and I was in the Scottish region, and I was active in the local branch prior to becoming a full-time officer. When I became the Divisional Secretary, however, I was then appointed as the Union representative on the Regional Council of the NFBTO, and participated in all their work: wages negotiations, as well as the other work that they engaged in, and of course attended conferences as a representative of my own Union. Now, that covers that situation. Interviewed c.1978 by Janet Druker, then a PhD student at the University of Warwick Interview – John Leonard Transcribed by Alison McPherson, alison.mcpherson@premiertyping.com, www.premiertyping.com Yeah, that’s really what I’m fishing for is that I’m not too clear about the breakdown between how much would have been covered in terms of negotiation by the Federation at this local level and how much would have been covered by each Union separately. What sorts of issues would have gone to the Federation as…? Oh, I follow what you mean. Well, in my own union, so far as Scotland, the Number 10 division was concerned, the wage negotiations for the building industry, generally speaking, were carried on for the union by the Regional Council of the NFBTO. As Divisional Secretary, however, I was responsible for negotiations in certain branches of the industry, and whilst not completely identified with the building industry, they nevertheless had an association when it came to a question of wages, and I was the chief negotiator for the granite industry in Scotland. I was also the chief negotiator for local agreements in the steel industry in which our members were employed, but I also participated at national level, even as the Scottish representative, in general wage negotiations in the steel industry. In the granite industry, I also negotiated on behalf our members employed in Northern Ireland, round Rostrevor and Kilkeel and places like that. So, that was the wage negotiations that I carried out, separate and distinct from the Federation, and purely on behalf of our own members. [Terrazzo] was another section that we negotiated wages in the Scottish field. So, there was these three specialist sections, had, to a certain degree, an affinity with the building industry, but not part of it. You’re suggested really then that quite a lot of your members were employed outside of the house-building industry as such, I mean either in steel, shipbuilding… Well, I wouldn’t say there was a lot. Well, take steel, for instance, I would say there would be roughly about 2,000 members in Scotland in the steel industry. In the granite industry, particularly in Aberdeen – that was the centre – there’d be about four to five hundred there, and there would be somewhere in the region of probably 200 in Northern Ireland, but there again, their employers, our opposite numbers in the employers’ side were separate and distinct from the building trade employers, you see. So, it was where you were involved in the building industry as such, you worked through the NFBTO? Yes. Yeah, that’s the distinction. In Scotland, it’s been said the job of a bricklayer and a mason was never so distinct as it was down South – was that true, do you think? Well, when you say distinct…what do you…? Well, in the southern part of the country, the stone mason was a separate trade from the bricklayer. Oh, they were, yeah. That’s true In Scotland, they were, because, in Scotland, whilst I was a Glasgow District Organiser, there was then in existence an organisation primarily dealing with masons, and it was known as the Building & Monumental Workers’ Association. Now, if my memory serves me right, and I wouldn’t be categorical on this, they subsequently merged with us, under what was then known as the Transfer of Engagements Order – it was during the currency or shortly after the War years, so that they merged with us, but prior to that, they were separate and distinct, and I had nothing to do with them. It was only when they merged with us that I took some responsibility. You don’t remember how it was they came to merge, would you at all, the details of…? Interviewed c.1978 by Janet Druker, then a PhD student at the University of Warwick Interview – John Leonard Transcribed by Alison McPherson, alison.mcpherson@premiertyping.com, www.premiertyping.com Well, I think that, probably, some of the things that brought it about was the certain amount of antipathy between masons and bricklayers. A mason would not be allowed to lay brick – this was getting down to the site level, and I think this was an aggravation that subsequently brought about the desire to see a merger, and when all was said and done, I think that…the other facet that probably prompted it or assisted it along the road was that it was becoming a dying trade, from the point of view of costs and the limitations that were imposed by local authorities in the usage of stone for house-building, because they were primarily in the building industry, not in the steel, [terrazzo] or in any other section. Yes. They merged, I think, actually, in 1942, so I wonder if the War had any effect on the situation… You certainly have awakened a memory – that’s true, about ’42, they certainly did merge with the AUBTW, under the then Transfer of Engagements Order. It had to be carried through in accordance with the legislation of the country. Yes. I can’t remember how many members they had. Were there many problems with the merger in terms of overlapping work of officials and so on or did they maintain a separate sort of existence within the AUBTW? Well, they had officials, but the size of the organisation, in those days, eh…I think they’d only a General Secretary and I think two full-time officers, covering the whole of Scotland, because they never went anywhere else – they never gravitated across the border, as it were. So that, they weren’t a big organisation in comparison to the AUBTW, so that was the strength of their full-time personnel. So they simply carried on working full-time for the AUBTW? Oh yes, they were taken – under the Transfer of Engagements, they were taken over without prejudice. In the post-War period, I suppose there were a number of changes in the industry, in particular the introduction or the consolidation of the Wartime practice of piecework, payment by result, and also the sliding scale arrangement. Did there seem to be, if you like, a transition? Did that seem to be a shift from the pre-War practices, or was it something that had been growing anyway in the earlier period? Oh, we certainly had the sliding scale. We had the…we had the differentials as well in Scotland at one time. We had a different rate. It was minimal, but it was nevertheless a different rate, as against the rest of the country, and we had…and in some cases, the grading of districts, as they had in England and Wales, but I think that we were able to get rid of the grading earlier than they did in England and Wales. We were also subject of course to the Essential Works Order and the Uniformity Agreement that was governing the civil engineering industry, and we had our problems in those days as well in relation to these two orders. Perhaps you could elaborate on that because I don’t know anything about this area. How were you affected by the Essential Works Order? Well, the Essential Works Order was purely a compulsive order and men had to do certain things that were somewhat different from the traditional methods or traditional practices that we had operated prior to the War, and there was strictures imposed as a result of the order. There was, so far as the Uniformity Agreement, from memory, the Uniformity Agreement, eh…contributed to a lot of difficulties because of eh…the determination of the type of work. We always claimed that work up to the cartilage of the kerb could be treated as civil engineering, but when it came over the kerb, we claimed that it rested with the building industry. But, the civil engineering had Interviewed c.1978 by Janet Druker, then a PhD student at the University of Warwick Interview – John Leonard Transcribed by Alison McPherson, alison.mcpherson@premiertyping.com, www.premiertyping.com encroached on this, and to a degree, had affected traditional work that was done by bricklayers, and could be done by anyone, as a consequence of the Uniformity Agreement. So that was the two features of these Orders. And they were introduced during the War… Oh yes. At the end of the War, did they cease to have any effect, or were they continued in practice? Oh, they lasted for quite a time. I couldn’t be…firm on when they disappeared, but they ultimately disappeared, the Uniformity, and indeed the Essential Works Order, which was purely under the emergency, War emergency. Yeah. No, what I meant was that they established practices which, by the end of the War, were probably accepted as custom and practice… In some cases, they were accepted. In other cases, they didn’t go down so well. They were tolerated – let me put it no higher than that, tolerated. But immediately the Orders were removed, then there was a return to the traditional practices. I’m trying really to account for the introduction of piecework in… Well, of course, I think every union in the building industry – and at that time, there were somewhere in the region of about 18 unions – I don’t think there was a union who would have permitted, voluntarily, the introduction of piecework or payment by results, but with the introduction of the Essential Works Order, it had as a corollary this payment by results scheme, that was…capable of alterations if you had…could convince the Inspectorate of the Ministry on the justification. It certainly created havoc up and down the country, so far as Scotland was concerned, in their abhorrence of this, but it was introduced as a consequence of a ballot vote of the membership of the unions, you know. They voted on the introduction of this, and the eh…for want of a better word, the malcontents in the unions, eh, claimed that there was a carrot offered the unions to accept this type of work, namely payment by results, and to a degree, there appeared to be some truth in that, up to a point. So that there was, eh, difficulties up and down the country in its operation. There was…the volume of work that was expected was laid down in a certain code, by the Ministry: so many bricks for so much. And the men were saying, well, we can’t meet that quota, so that we had…the only course that we could adopt was, as I say, get in touch with the Inspectorate, get an examination. In some cases, we were successful, speaking purely of Scotland – I don’t know what happened in England and Wales. In some cases, we were successful in getting an alteration in the figures, to the advantage of the men of course; in other cases, we failed, but in some cases where we were successful, I found that eh…I was misled by my own members, because, immediately the figures were altered to their satisfaction, they went mad and they made colossal sums in relation to this…the monetary reward for this scheme. Why do you think the members favoured the introduction of the scheme? It had been opposed for so many years by the building trade unions. Well, they didn’t favour it. It was a question of a ballot vote, and they were promised a wage increase if this went through. Ah, they got the wage increase anyway, yes. They wouldn’t have got the wage increase that they had been offered, but they got a…shall we say, an enhanced wage increase if the vote went in favour of its introduction. Interviewed c.1978 by Janet Druker, then a PhD student at the University of Warwick Interview – John Leonard Transcribed by Alison McPherson, alison.mcpherson@premiertyping.com, www.premiertyping.com That was during the War years? During the – the introduction of the Essential Works Orders. So that, at the end of the War, presumably, they reverted, did they, to…time rate system? At the end of the War, the Order disappeared, or was removed, but it then became an issue for the collective machine of the industry, the National Joint Council for the Building Industry, and, in the course of discussions, it was agreed that there would be schemes of incentives introduced. They didn’t use the phrase “payment by results”. They renamed it and called it the incentive scheme, and that continued, and it even continues until today. Yes. And all of that was arranged through the NJC? Through the National Joint Council for the Building Industry and the Scottish National Joint Council, because we were a separate National Joint Council, for a long time. I can’t be…I can’t just quote the date when the two…Councils merged, and as far as I knew, or was led to believe, the reason why there was opposition to the National Joint Council taking over the Scottish National Joint Council was largely one for the employers, who were a bit hesitant about losing their identification by going into the larger organisation, but they subsequently went in and now we have one for the whole of the country now. Yeah. So, presumably, it was after the employers had gone into the English National Joint Council that the Scottish plasterers and Scottish slaters and tilers and these other Scottish organisations started looking perhaps to merger with the English organisations. It would make sense, wouldn’t it? Well, the Scottish plasterers, if my memory serves me right, it was a good period after the War years when they had discussions with the English plasterers that led ultimately to a merger of these two organisations. But, strangely enough, the National Federation of Building Trade Operatives, of which they were constituents, was the Scottish and the English plasterers, and indeed, the slaters. They participated in discussions within the NFBTO in trying to get an implementation of the TUC’s policy on rationalisation of trade unions, but it fell by the wayside because the…the plasterers, having merged together, subsequently went into the T&GW, as did the Scottish slaters. But one of the slaters’ unions, centred on…centred in England really, they merged with the AUBTW. That was ASTRO? ASTRO, they merged, but the Scottish Slaters went into the T&GW, as did the Scottish plaster…well, the plasterers’ organisation, they went into the T&GW. The question of amalgamation, of merger, and the need for consolidation of the trade unions was raised originally as a resolution through the NFBTO in 1959. Do you have any sense of where the resolution comes from? Is it from a particular region or…? I can’t recall its origin at all. I know…but I know that it was mooted by some organisation and the only thing that one could say with any real honesty is that it was largely projected because of the Trade Union Congress advocating a policy of rationalisation, on the basis that there were too many unions, particularly in the building industry, who were overlapping. They were all doing the same job, so that there was a valid reason for trying to get an amalgamation of these unions and a reduction in the numbers. Yes. But the TUC were…I looked through the reports, and they don’t seem to have been heavily bothered, for example, by demarcation disputes in the building industry - I mean the number of Interviewed c.1978 by Janet Druker, then a PhD student at the University of Warwick Interview – John Leonard Transcribed by Alison McPherson, alison.mcpherson@premiertyping.com, www.premiertyping.com disputes in which building unions were involved, which are reported in the TUC reports for those years, they’re not terribly high. No, because we attempted to solve them within our own structure. We were not without demarcation problems, and indeed we had our demarcation problems, eh, so far as bricklayers were concerned, even in the steel industry, as you probably know. But we had our problems of demarcation in the building industry and it’s perfectly true that eh…we never troubled the TUC much with them. I think, in the main, the only problems, and these were minimal, was a question of poaching of members, where we went to the TUC when issues of that character manifested themselves. Do you think then there was an increase in the number of demarcation problems which your union was facing in this period, say over the post-War years generally? Well, demarcation problems, I think they disappeared with the mergers of these unions, you see, and we don’t have them now at all. Sure, yeah. We don’t have them. No, I mean in the period prior to the mergers taking place, were the number of demarcation problems increasing? I don’t think they were so great really, even prior to the mergers. They weren’t so great with our unions. We had the occasional blow-up, but we were able to resolve or at least effect a compromise situation, you see. Would you like a coffee? Thanks very much – yes, that would be very nice. Now, I usually make it half-and-half – do you mind? That’s lovely, yeah. Just I’ll do it… [Recording cuts] …and the firms, but what one did find, at least I found, was that some of the national firms gravitated into Scotland, where, prior to the War, they never were there, you see, and I think this was general all over the place because…digressing for a moment, we had eh…we had our problems with some of the national firms who went into Liverpool, and of course they ran into difficulties in Liverpool. Indeed, some of them said that they would never go back into Liverpool. Yeah. In what context, sorry? Because of the industrial problems, the industrial strife that seemed to manifest itself in Liverpool. And one finds it in other industries as well - the motor car industry is a typical example, you see, Halewood and places like that. But so far as the building industry is concerned, speaking purely of Scotland, I think the only change we saw was the…the incursion of national firms into the Scottish area. Which particular firms? Interviewed c.1978 by Janet Druker, then a PhD student at the University of Warwick Interview – John Leonard Transcribed by Alison McPherson, alison.mcpherson@premiertyping.com, www.premiertyping.com Well, we had Wimpey coming in there, and we had eh…[Holland, Hanlon & Cubit] and you had eh…quite a few. I can’t just recall the names of them, but that was two particularly, Wimpey, and [Holland, Hanlon & Cubit]. It’s a period when, I suppose, lump labour is beginning to become more evident in the building trade, isn’t it? Oh yes, that’s when it started, after the War. You had the incursion of the labour-only merchants, got very rampant in many parts. I don’t think it affected Scotland as forcibly as it did in England and Wales till a much later period. I could never trace any evidence of lump labour, eh...up to the time that I had left Scotland, but after that, it certainly developed, and we had it countrywide then. Why do you think that was? Was Scotland better organised? Well, I thought so. I was always under the opinion that we had eh…a better organisational set-up than across the border here. And you think that helped to prevent…? I think it helped to eh…keep them at bay, as it were, but then, with the War years, and particularly the incursion of the Essential Works Order and the Uniformity, this sort of engendered an attitude of mind amongst the members that, “Well, what’s the point of being a member of the union?” and so on, you see. This was an attitude that became very… Were you finding that there was any change in the nature of the old skills that was required in that period? No, I don’t think there was much change in the skills. The only thing was that…because of the circumstances, we had the advent of prefabrication of materials, you see, and the structures took a decided change that eliminated quite a lot of traditional work that the bricklayer or the mason formerly had. They put a side of a house or a complete house by the crane and very little brickwork or masonry. Do you think this was a response to the sorts of…well, I won’t say “fiddles”, but to the way that your members were responding to payment by results, to some extent? Well, it may have been an attitude of mind dictated by that – it may well have been that. Did the union object at all to the prefabrication, to the introduction of prefabricated units? Well, I don’t think there were many objection – there was a real objection, and the objection was largely determined or dictated by the principle that the employers applied in relation to the type of labour that they would use for this structure. For instance, if we consider that they were taking away the livelihood of a bricklayer in the particular system that they operated, then we took some exception to it and tried to ensure that, if there was to be… I don’t think we could object to the systems, but we had an obligation to try and ensure that there was a balanced gang and that every section should have at least its share of the work. What’s sorts of technical developments were taking place in the post-War period? Well, as I say, there were these complete units, where formerly you would have built a brick wall, and these complete units took the place of that. Yeah. Were there any other kinds of…? Interviewed c.1978 by Janet Druker, then a PhD student at the University of Warwick Interview – John Leonard Transcribed by Alison McPherson, alison.mcpherson@premiertyping.com, www.premiertyping.com No, I don’t think… In the main, that was about the bulk of it. Any other changes would probably be affecting the plasterer, for instance, where formerly he did his work insitu, it had been transformed or transferred to a process of slabs or plasterboard. So, this was…this was the only changes really. When were breeze blocks…? Oh well, breeze blocks had been on for a long, long while because the… Again, I don’t know why, I’ve never been able to really find out, because, in the old days, when I started in my trade, we never had many breeze blocks because we had the stud partitions – it was a wood structure, and it was lathed and plastered. Now, that was a trade that disappeared completely, and they used to have what they called the lather. There’s no lathing done nowadays. You see, it’s all breeze blocks, plasterboards on ceilings… And I suppose concrete would have affected your members, would it? Oh well, I don’t know that concrete made much difference, other than probably the outside, poured concrete, you see, the outer frame. But were concrete buildings – I don’t know about Scotland, but were they becoming more common? Oh, they were concrete, oh yes, there was concrete building went on in Scotland. Yeah. No, I just wondered if this was something that really seemed to develop during the War, with civil engineering and so on. No, I wouldn’t say that it developed during the War. It certainly eh…it certainly…increased…the tempo of the utilisation has increased, eh, probably because of the need and the shortage of other basic materials that prompted its…speeding it up. But I wouldn’t say that it was following the War that determined or dictated its innovation. We’d had it before, before the War, not to the same extent, it’s true. Perhaps we can come on to the question of organisational change, because, in 1952, John [Startey] became Assistant General Secretary. He took in the National Builders’ Labourers Construction Workers’ Society. Oh yes, they merged with us as well, that’s true. That’s right. That was a bit of a break for your union really, wasn’t it, in the sense that they wereWell, it opened the door for the organisation of labourers, attendant labourers, and that was an organisation – I can’t just recall how much strength it was… They had quite a number of officers in London, but their spheres of influence, I think, they didn’t go…beyond Newcastle. I think that was the furthest afield that they went. But as you say, reminded me, they certainly merged with us in…I believe it was 1952. I wouldn’t say what particular month. The discussion, apparently, had started when I came down, and became a reality, as I say, in 1952. Was it that the AUBTW was thinking of recruiting labourers more generally then or that they were quite happy to have…? No, I don’t know that it was, but I think the factors that more or less prompted it was that the NBL, probably their…their proper home should have been the T&GW, for instance, but they could never get on with the T&GW, so that it was largely their promotion of the need, and having taken Interviewed c.1978 by Janet Druker, then a PhD student at the University of Warwick Interview – John Leonard Transcribed by Alison McPherson, alison.mcpherson@premiertyping.com, www.premiertyping.com them over, then it opened the door for the AUBTW to start recruiting labourers, eh, much to the displeasure of the T&GWU in many areas, particularly in local areas. Yes, the T&G must have been rather peeved that you…you were moving in… Oh, they were [laughing], they were! Were there discussions at the national level about this? Did the complaint formally to you? I don’t think there was discussions at national level on it, although the…except in conferences of the NFBTO. You got the eh…jibe from officers of the T&GW about us taking…now opening our doors and instead of being designated a craft union, we were now an industrial union, and this is what they were claiming. Of course, the boot’s on the reverse foot now because they, by taking in two of the very oldest, old crafts, now say that they’re capable of recruiting craftsmen. Was that simply a retaliatory move, do you think – you got the labourers, so they felt they wanted to go for the craftsmen or…? I’ve never been able to really ascertain, although I’ve spoken to many of their former officers, why the two craft unions went into the T&GW. I’ve never been able to find out the reasons. I don’t think it was eh… I wouldn’t like to say what really prompted them, other than that there were some difficulties with the plasterers’ union within the NFBTO, and I think it was in a measure of pique that they certainly went there. They had talked with us, but couldn’t make any progress, and similarly, so had the Scottish Slaters, but then, the Scottish Slaters, their objective at that time, as far as my memory serves me, was that I think they would have been prepared to merge with us, but they wanted to merge on the principle that they would be a union within a union, something like old… There was one in the T&GW that was more or less a union within a union, the Mechanics, I think they called themselves the Mechanics, but so far as they were concerned, when their General Secretary retired, in accordance with age group, then that feature disappeared, you see, so that they’re an integral part. I think the same can be said of the present situation with the AEU because the Construction Engineers Union, they’re now inside the AEU, but they attempt to operate on the same principle, that they are a union within a union, you see. So, the Slaters, the Scottish Slaters would like to have done that, or would have come into our organisation on that principle, but we couldn’t countenance that at all. Yes. So, the problem with the Slaters really then was the organisational one. What was the problem with the Plasterers, in relation to their discussions with you? Well, I think it was a bit of pique because they didn’t get a certain position within the Federation. It was a…it’s maybe wrong to say this, but this is the belief that I held, that, because their General Secretary had been ousted from the Executive of the Federation, he certainly didn’t play any part in trying to bring them into the AUBW, but rather did he favour going elsewhere and they ultimately went to the T&GW. Yeah. He was ousted from the Executive. Who got in in his place? Oh hell…that goes back a long time ago – I can’t just recall it. He was ousted at a conference at eh…hmm… What I’m trying to get at really is why would he feel that the AUBTW was responsible for that within the Federation… Oh no, he didn’t attribute it to the AUBTW! Ah. Interviewed c.1978 by Janet Druker, then a PhD student at the University of Warwick Interview – John Leonard Transcribed by Alison McPherson, alison.mcpherson@premiertyping.com, www.premiertyping.com Oh no, he didn’t attribute it, but you’ve got to appreciate that…the NFBTO tried to play a part in forming mergers you know, the Executive of the NFBTO. Indeed, conference resolutions at NFBTO projected the idea of bringing closer together the unions. So that, he didn’t blame the – it wasn’t a question of blaming the AUBTW, it was a question of blaming some of the other unions within the NFBTO, and I think one of the unions particularly that he felt aggrieved at the time was the Plumbers’ Union. Now, there again, I always accepted them as a craft union, and I’ve never been able to fathom why they went into the ETU – that’s where they are at this present time. Yes. So, coming back to this question of the Plasterers, I think it’s an interesting point. They talked to you and they weren’t happy about, for example, about the suggestions about the number of people they should have on the Executive and so on. Yeah. Were there any other issues that you can think of? Not that I recall. I want to be honest, I cannot recall any other issues. Yeah. What sort of relationships traditionally existed between the AUBTW and the Plasterers? Was it traditionally a good relationship? Oh, they had a good relationship, oh yes, had a good relationship. Not that there’s anything traditional in the actual craft as such, but they had a good working relationship so far as the organisations were concerned. Obviously, they were grouped together in the negotiations as part of the trowel trades groups, to talk to the AUBTW. Yes, yes, yes. And they did, at that level, seem to have something in common. They participated in the discussions under…in the trowel trades, but they, as I say, they couldn’t see their way to come into…couldn’t see their way to finalise it. Do you think that the…I don’t know, perhaps the terms and conditions for trade union officers within the AUBTW were not as good as they were within the Plasterers? Oh, I don’t think there was much difference really. I think there was a fairly equal situation, equal position existed, you know. I was just wondering, because it’s sometimes been argued that the AUBTW’s officers had conditions which were not as good as those of, say, the woodworkers, and that there might be a reason for unions looking for amalgamation to look elsewhere. I think that would be true to say that because I believe that….although it wasn’t the dominant factor, so far as we were concerned. But the ASW conditions were much more favourable than ours, so far as our officers were concerned. But we had a part-time Executive, as probably Mr Lowthian has told you. We had a part-time Executive, and within that Executive there were eh…conservative attitudes, if I put it no higher than that, who felt that if…if we did go through with it, then we were losing our identification. This was the attitude of some of them. I think, in the end, we were able to baton that down. But the improvement that the officers got, it wasn’t prompted by the officers, that this should go through. It wasn’t a selfish attitude, by saying, well, Interviewed c.1978 by Janet Druker, then a PhD student at the University of Warwick Interview – John Leonard Transcribed by Alison McPherson, alison.mcpherson@premiertyping.com, www.premiertyping.com let’s go in there because we’ll fare better than we do under our own organisation. There’s no question about it: conditions were more favourable. You think people were looking very much more at the…the wider [leagues] of the situation? I think the wider membership were quite…quite keen to see a merger. I think they were beginning to see that, well, we had our problems, and with the escalation of costs, eh, the situation financially was becoming a bit difficult, in all organisations. One didn’t escape it any more than the other, and the contribution situation was always one that we had to give very serious thought to, and we promoted within our Executive an ideal that, by a certain time, we would have a…a contribution from our membership that would equate to at least one hour’s wages, but we never achieved that. But that was our objective. That’s actually very low, isn’t it? Yeah. Well, for years, we had a contribution of nine-pence per week, and that was antiquated when you think in present… Even if you think in terms of 42 to 62, it was antiquated and we gradually had to improve it from 42 upwards. But, as I say, our objective was set on the principle that there should be at least one hour’s wages for the contribution to the trade union. You say that there were conservative elements in the part-time Executive of the AUBTW. Oh yeah. Are there particular areas or particular individuals that you feel-? It was just certain individuals. Well, it meant, first of all, we had an Executive of eh…we had an Executive, a lay Executive, of 10, plus two, 12 – we had a lay Executive of 12, you see. Yes. The Scottish area had two representatives because we had to, under the instrument of eh…transfer of engagements, we had to give coverage for the old Building & Monumental Workers. Under the NBL, we had to give coverage, and under the Operative Stonemasons, which was one of the organisations that merged with and became the AUBTW in 1921, we had to give coverage to them. So, we had 12, yes, 12 Executive members, part-time. Now, the arguments that took place was: how many are we going to get on the new Executive if we go in? And the mere fact that it was a full-time Executive, not a part-time Executive, created [laughing] the selfish aspect amongst them all – well, who was going to be the number…whatever the number might ultimately be? And, as I say, this engendered some thoughts in their minds. Who would you say was putting up the resistance mostly to going…? Well, there would be resistance from men who were a bit…advanced in age, and they would, eh, probably think that they should get coverage on a full-time Executive, even though their period of office might be less, from the point of view of the retirement age. I think this was a facet that became very pronounced. So that, that’s why I say there was a conservative attitude in the...plus the view that quite a number of them took that eh…well, we’ll lose our identification in no time, or we’ll be dominated by the ASW, losing sight of the fact of course that, at the time of our merger, there already had been two merger…no, one merger, at least one merger with the ASW. The Painters had gone in by then, you see. Yeah. So, the question of who would go onto the Executive was obviously a key one. What about the people who didn’t go on, you know? They…obviously, there would be toing and froing at the time and… Interviewed c.1978 by Janet Druker, then a PhD student at the University of Warwick Interview – John Leonard Transcribed by Alison McPherson, alison.mcpherson@premiertyping.com, www.premiertyping.com Oh well, they went out – oh, they went out! Whenever the merger took place, their office ended. Was there any attempt to incorporate them into the regional structure of the woodworkers and painters? No. No, there was no attempts to… Because that was part-time anyway, you see, so it made no difference. What was the attitude of Communist Party members on the Executive to the merger? Did they…on the whole, were they in favour of it? Well, I don’t think they welcomed it because of their long antipathy against…and it prevailed for a long time, the antipathy against the ASW, you see. This was… But we only had eh…we only had two Communist Party members in our Executive, you know – no, three, I beg your pardon, there was three, at the time, or the three or four years prior to the merger. We only had two or three…three. That was Bill Smart, wasn’t it? Bill Smart was one. Albert Williams was the other, and the third man was the fellow from Edinburgh, Darcy, Hugh Darcy – these were the three. So, they did…all the whole, they were rather, what…? Well, Smart, Bill Smart wasn’t too keen on the merger at all. He was always resistant to it, and he could, at times, rely on the support of Williams and Darcy. Did he have one of the full-time positions? Did he go over as a full-time…? No. He didn’t. So, yes… No, they were lay members, lay members purely. Yeah, sure. No, I was wondering if any of those went over to the new UCATT Executive after the merger. Oh yes, they did, oh yeah, yeah [laughing], two of them went over! Yes, Williams and Darcy? Darcy and Williams. Yeah. So, in fact, they were quite well-placed within the merger vis-à-vis their previous strength… Well, when it became effective, and the figures of representation had been agreed, here you had 12 men competing for three seats, so one can visualise… One doesn’t really have to be there to see it, but can visualise the machinations that would go on. And of the 12, you had eh…nine craft representatives and three…10 craft representatives and two general section or labourers’ representatives, so that there was 12 competing for three seats, as it actually turned out at the end. We got…we got five seats on the Executive. I don’t know whether Mr Lowthian told you that. Interviewed c.1978 by Janet Druker, then a PhD student at the University of Warwick Interview – John Leonard Transcribed by Alison McPherson, alison.mcpherson@premiertyping.com, www.premiertyping.com Yeah. We got five seats on the Executive, and because they had a ballot vote in the Council Chamber, we had three Executives, the Assistant General Secretary and myself were nominated as the Executive members, and Mr Lowthian was taken over, without prejudice as the…the eh…Sectional Secretary, a post that would not be complete, not be replaced on his retirement, and that’s how it ended up. Now, we have ended up with a…Mr Lewis, who was the Assistant General Secretary of our union at the time, he’s now a National Officer because they’ve established, as they envisaged establishing, a full-time Executive of seven, because, quite frankly, it was too unwieldy at the time. You had three painters, you had seven joiners, and you had five AUBTW representatives, so it was too unwieldy really, as an Executive, and they envisaged, within five years, getting down to an Executive of seven, and they have achieved that, and the only remaining Executive members of the old AUBTW is Williams and Darcy. Yes, it’s gone down quite rapidly, hasn’t it? Yes. Oh, we had another Executive member – I beg your pardon. We had…there was Lewis, Williams, Darcy, Sanderson, and myself, five, plus Lowthian. I retired – Lowthian retired in ’73. I retired in ’74. So that left three – no, it left four, beg your pardon, that left four. And the envisaged, as I say, getting down to seven. So, Sanderson became a National Officer, as did Lewis, and in accordance with the electoral procedure, there had to be an election, and Darcy and Williams were re-elected for a term. I see, yes. What was the attitude on the whole towards the ASW? I mean, traditionally, they’re…you know, they’re perhaps rivals, they’re a bigger organisation, and they’re also…they do seem to be a more…a more conservative organisation, in some ways, in relation to their own craft traditions. Well, there was an attitude that they…they weren’t as forceful as one would have thought they should have been, having regard to their numbers, and that they were prepared to accept things that the other craft unions would not accept. This was the…this was the situation. And there was always the antipathy of the AUBTW against the ASW, even in the National Federation of Building Trade Operatives. It’s…I don’t know…obviously sort of coincidental, alongside the[End of Recording 1] [Recording 2] …the ASW on the Federation – do you think they were trying to get shot of it anyway? Well, I don’t think they were entirely happy. On every occasion within the Federation, they were always resentful of many things that happened in the Federation, but as I say, I think they knew and they were knowledgeable that, if we could effect these mergers, a reduction from 18 down to about three, then the day or the need for a Federation was becoming more evident that it was no longer necessary. That’s why, when eh…we carried on the Federation until virtually the retirement of Harry Weaver, who was the General Secretary of the Federation, and had been President of the AUBTW prior to me taking over. The Transport & General Workers continued to make overtures to you, didn’t they, until, more or less, until you went into the ASW? Interviewed c.1978 by Janet Druker, then a PhD student at the University of Warwick Interview – John Leonard Transcribed by Alison McPherson, alison.mcpherson@premiertyping.com, www.premiertyping.com Oh yes, they were always saying…they were always saying that they would like…they would have liked us to go into the T&GW, but…there were points of view expressed, you know, within our Executive that, if the need arose, or if we were forced to go somewhere, we certainly wouldn’t have gone to the T&GW. We may have gone to the G&MW, for instance, if one went anywhere. And that was even being ventilated even during the discussions that took place with representatives of the ASW, because they were not too happy at some of the features that were being advanced by the ASW as terms for a merger, and the biggest factor, as I say, was the…the number of our representatives that would be ultimately on it. It took them quite a while to get the five that they subsequently did get. Presumably, as it was a transfer of engagements, you had to accept the ASW Rule Book? You would have gone in on the basis of…? Yes, yes, yes. Did that present problems at all? Were there major differences which…? I don’t think it… On the surface, it appeared that it may have presented problems, but in the application, I don’t think it made any great difference, And, so far as the membership was concerned, they had the option, and they had to exercise that option through the ballot paper. They exercised their option either to accept the rules and benefits of the ASW or to still contribute under the old scales of the AUBTW plus the benefits that they would receive. Now, some of the benefits of the AUBTW were much more advantageous than those of the ASW, but in spite of that, the numbers who opted out were em…very few. They were nothing to what the arguments would have led one to believe there would have been. This was the effect of it. Earlier on, you said something which intrigued me. You said that the AUBTW, if it had to go somewhere, and if it was really desperate, would have gone to the G&M rather than to the T&G. I can understand the AUBTW saying we’re not going to any of these general unions. Yeah. But if it had a choice, em, I can’t understand why it should prefer the G&M to the T&G. Well, what I did say was this: that if the need arose, if we had been forced to go, and by that I meant to infer that, if we couldn’t get satisfactory terms with another craft union, the only other course might have been a general union. But we always held the view that, so far as the building industry was concerned, we never treated the T&GW as being representative of the building labourers, and to that end, this particular expression of opinion emerged, that if the need arose, if we were forced, through economic circumstances or financial stress, then, in preference to going to the T&GW, who were inviting us to discussions with them, we would have preferred to have gone to the G&MWU, believing that they were more representative of the building industry than probably the T&GW. But they had far less members… Oh, they had far less members in the G&MW, it’s true. Sorry, so I don’t understand when you say they were more representative – in what sense do you mean? Well, we always believed that they gave better service to whatever membership they had in the building industry, rather than the T&GW, and the old phrase was that they were only interested in skulls – it’s a vulgarism, but nevertheless, this was the attitude. They recruited men, but they never serviced them. This was the…was the attitude of mind, and it was that that more or less Interviewed c.1978 by Janet Druker, then a PhD student at the University of Warwick Interview – John Leonard Transcribed by Alison McPherson, alison.mcpherson@premiertyping.com, www.premiertyping.com caused that expression to be made that, in preference to going into that lot, we’ll go to the G&MW! Yeah. But right up to the amalgamation, there were resolutions appearing from some of your branches that you should go into the T&GW… Oh yes, there were some very favourable disposed, quite a number of branches were disposed to going in there. So, given the reasons you’ve outlined, that the membership would get a raw deal from the T&G, why were some of the membership wanting to go into the T&G? I think it was political rather than [laughing]… Yeah… You see, many of the…many of the Communist rank and file membership were favourably disposed to the T&GW. Cousins was a militant, Jack Jones was a militant, and to that end, they saw that their…their future probably lay…was a much better possibility than anywhere else. Yeah. So, I had an impression that the Communist Party was rather loosely in favour of one union for the building industry, but what you seem to be suggesting is that the Communist Party in fact wanted to see a merger into the T&G. Yes, because I don’t think – I think that, in many respects… Well, take our own organisation – that was purely lip-service, the idea of one union for the building industry, because the difficulties were eh…were voluminous, the difficulties that one could see, and I don’t think that we… We couldn’t say, even today, that we’ve got one union for the building industry, and I don’t think…I don’t think we’ll see it in the foreseeable future, because how can you get it now that you’ve got three presumably craft unions in the General Workers or in the electrical trades? How can you see them coming into…establishing one union for the building industry? It was a belief that we...I always held, that our eh…solution undoubtedly lay in the establishment of one union for the building industry. In a sense, shortly after the discussions began, I suppose, it was realised that what was being discussed was more of a…I suppose a general union really for the building industry. It wasn’t just to get the old idea of an industrial union. Well, I think that the three unions that now form the UCATT firmly held a belief in one union for the building industry, but they had nevertheless to contend with certain attitudes within their own Executives, and, in some cases, within their own membership, and I think there was… If one could take our own membership, by and large, I think the majority of our own members, rank and file members I’m speaking of, favoured going into the craft union rather than going anywhere else, believing that it was a step in the right direction. Yes. Do you think…coming back to this question of the Transport & General, because, obviously, it is a sort of key question in the way that the line-up eventually worked out – do you think there was a change in their policy towards craft building unions, in the sense that, for a long period of time, they did stick to labourers? They didn’t really try to recruit, poach your members and so on. Or do you think that they’d always…that was the direction they’d always been moving in? Well, during the existence of the NBL, you know, they had difficulties with the T&GW and the poaching of members, and I think that… I think that the only approaches or approaches from the T&GW only started to emerge following the NBL coming into us, because it was then that they said that eh…it was generally said by T&GW people that now the AUBTW have got the NBL, Interviewed c.1978 by Janet Druker, then a PhD student at the University of Warwick Interview – John Leonard Transcribed by Alison McPherson, alison.mcpherson@premiertyping.com, www.premiertyping.com they’re now an industrial union, they’re not a real or true craft union, they’re an industrial union, and to that end, they felt justified in launching approaches to us to eh…join them. Yeah. And they continued, as I say, and this will be probably recorded but you’ll have to disregard it, purely an opinion, if one goes on the basis of eh…present situation, I’m led to believe that…and I’ve seen it, I think I’ve seen it in cold print, that they’re even discussing now the possible merger – whether it will materialise is another story – with the ETU and PTU. Chapple is apparently discussing with…well, it was with Johns, I believe, that possibility. Now, that, eh…pre-empts, to me at least, that they now think that they were right to recruit craft organisations into their ranks and subsequently their membership, having regard to the Scottish Slaters and the Plasterers being an integral part of their own structure. Yes, they’ve got their foot in the door… They’ve got their foothold, you see. And the foothold for launching an approach to us were because they said, well, you’re no longer a craft union, you’re an industrial union. Do you have an idea when the first approach was made? No, I can’t just recall when it was made. I think it was made…purely by virtue of the fact that it was probably a discussion, eh, between Jack Jones, probably Cousins, with George Lowthian, when they were in the General Council of the TUC, that they were meeting each other every other month, you see – probably talking, and George reports this to us. I don’t think it was ever put actually in writing. Yeah. No, only once – I’ve found it in writing once, shortly before you went into the ASW. Did you? Oh, right. But that would have been in, what, the mid-‘60s sometime? It might have been, yes, it might have been. You see, as Assistant General Secretary, I was primarily in the office, so I didn’t radiate as the General Secretary did. You referred to the TUC. What sort of role do you think they played throughout the question of amalgamation? I mean, they did start talks, didn’t they, about, what, ’62…? I don’t think they actually took an active role in it, other than eh…their respective general secretaries, [Feather] or, subsequently, Len eh… Well, it was during [Vic Feather’s] day, probably talked to George Lowthian and eh…reminded him of the policy of the rationalisation that the TUC had carried. Yes. According to the documents, there was…there were a number of discussions which took place under the auspices of the TUC, I mean, perhaps one or two a year, at which the trowel trade unions… Oh yes, there were, there were discussions, it’s true, and I think that they were primarily arranged in order to try and see if they, as they…as a TUC, could have helped in any way to resolve some of the apparent differences that existed. Yes. Yes, it’s sometimes said that the TUC was, in a sense, pushing or encouraging the unions into amalgamation, and I’m just wondering whether they were, to some extent, encouraging Interviewed c.1978 by Janet Druker, then a PhD student at the University of Warwick Interview – John Leonard Transcribed by Alison McPherson, alison.mcpherson@premiertyping.com, www.premiertyping.com simply unions along the paths they were already going along, you know, rather than being the initiators. I don’t see the TUC em…as having started the ball rolling, but they were… I wouldn’t know what the General Council of the TUC, what action they took, other than through their General Secretary, to protect this policy that they had established, namely, that there was a need. I think they recognised it as well as we did, that there was a need for rationalisation. There were too many unions. Even within the TUC, there were too many unions, and if one could hammer…flatten them out to a certain level, eh…then it was advantageous not only for the TUC but advantageous for the membership of the respective unions. We talked a little bit earlier on about the question of sort of rank and file, if you like, attitudes towards the merger and, generally speaking, you gave me the impression of resistance, of perhaps a sort of conservatism… Well, no, what I did say was this, that…the attitude of…within the Executive was a bit resistant, and I had formed the impression, because of my travels, that, if it got really down to the rank and file membership, they would have favoured it much earlier than it actually took place. They recognised it, you see. Yes, I see, yes. You said, sorry, I think what you said was something about them going…preferring a craft amalgamation… Yeah, yeah. Yes. Do you think that the statutory requirements on amalgamation up to 1964 held up the process? In other words, in 1964, there was the Trade Union Amalgamation Amendment Act, which obviously…it allowed transfer of engagements and so on, on a more simple basis than had existed previously. I think, so far as the legislation was concerned, I think it was much easier, under the Transfer of Engagements Act, to effect a transfer, although eh…following that, I haven’t seen any evidence of serious difficulties in effecting mergers or transfers with the later legislation. I think it has worked fairly well. You see, if I – harking back to the B&MWA merger, the Scottish Building & Monumental Workers, you see, you had, again, a minority of malcontents, particularly in Aberdeen, who said that we engaged in sharp practices under the Transfer of Engagements, and as much as that we effected it when quite a number of their members were serving in the Forces, and you…they claimed you engaged in sharp practices. We were able to disillusion them, that we had complied strictly with the law as it was laid down, but it lasted for a long while, some of these feelings, you know, particularly when they came back from the Services. Yes. The problem with Transfer of Engagements seemed to be a feeling that a union was being taken over and certainly theWell, this – yes, that was the attitude, that’s true, that’s true! The B&MW said that it was Big Brother taking us over – we were the small fry, and come hell or high water, we intended to get rid of them, as a union, as a unit. Do you think that was one of the problems which the AUBTW faced, say in the mid-‘60s, when it was talking to much tinier organisations? I mean, even the plasterers were… No, I don’t think so, no. You don’t… Because there was a discussion about a vacuum union, a holding union, to which all unions could transfer their engagements, and it seemed to me that that was a procedure Interviewed c.1978 by Janet Druker, then a PhD student at the University of Warwick Interview – John Leonard Transcribed by Alison McPherson, alison.mcpherson@premiertyping.com, www.premiertyping.com suggested for the purposes of avoiding a situation in which unions had to transfer engagements to the AUBTW. No, I don’t think, at that time, that that was the situation. Mm. Why then was the holding union proposed? Beg your pardon? There was a holding union, a vacuum union, was proposed – this came up in 1964/65, and it was suggested that all of the trowel trade unions would transfer engagements into this new union. Oh, aye, I remember, aye, I remember something about that… I never put…put much stress on that situation at that time, you know. You just didn’t think it was feasible? Well, personally, I never thought it was a feasible way in which to do it. I think the best way was that…the way that we ultimately did it. I don’t think you could have satisfied the Executives of the trowel trade unions… I don’t think you could have satisfied them by the establishment, as you say, of a holding union, because it was only…it would only have been a temporary situation and one that could have been overturned by any one constituent, so that I never held much to that point of view at all. It’s just that, when it came to the final question of the AUBTW transferring engagements to the ASW, and at a time when the painters had already decided to do that, there was a reluctance I think on the part of some of the…some of the Executive to the procedure of transferring engagements. Again, I think the AUBTW then maybe felt they were being taken over. Oh yes, yes, well, that’s true. There was an attitude of mind within our Executive that, as I said earlier, the attitude was determined on the principle that, if we go in here, we lose our identification in no time, and what was the general approach of the AUBTW would disappear entirely and we would…to all intents and purposes, become part and parcel of whatever strategies the ASW would apply, as they had been applying over the years. How far do you think that George Smith was concerned to get the new union established, to get UCATT established? Oh, I think he was wholeheartedly in support of it. Indeed, he made it abundantly clear on…two meetings that I attended that eh…and I think he was not unmindful of the financial situations of both our organisations, that if we don’t do it, or if we don’t get it through as speedily as possible, then it might become a question of Hobson’s choice to someone, to someone, to one of the unions, and to that end, I think he lent his support to the need to effect this merger. I was only in doubt to the extent that, previously, the ASW had been talking to the Woodcutting Machinists and to the Furniture Trade Operatives. Yes, yeah, yeah. And it seemed to me that, insofar as the woodworkers wanted to go anywhere, it was really to the other woodworking trades. Yeah, that’s true. I know that they had discussions – it’s only hearsay evidence, so I can’t put too much stress on it. I met both the…the then General Secretary of the Furnishing Trades, eh, and the General Secretary of the Woodcutting Machinists, when they were operating as separate Interviewed c.1978 by Janet Druker, then a PhD student at the University of Warwick Interview – John Leonard Transcribed by Alison McPherson, alison.mcpherson@premiertyping.com, www.premiertyping.com entities and that… I repeat, it’s only hearsay evidence, and one can only accept what was said. Neither of them were too keen to see…effect a merger with the ASW because of the domineering attitudes of the EC of the Federation – eh, of the ASW towards their own individual unions. And you’ll probably have seen, in the documentation that you have at the University, that that ended up purely by a merger of the Cutting Machinists and the NF…the National Furnishing Trades. You say the domineering attitude of the Federation, you said? No, of the…Woodcutting Machinists – eh, the… The ASW? The ASW Executive, yeah. Yes. I see. Would they have been in a separate employers – would the ASWM, the Woodcutting Machinists and the Furniture Trade Operatives, have negotiated with a separate employers’ body? They had, but they also participated in the National Joint Council, because they had an association, so far as some of their membership was concerned, with the building industry, so that the Woodcutting Machinists had a representative on the National Joint Council, in the person of Charlie Stewart. The Furnishing Trades had a representative as well. Now, I just can’t recall who he was… It wasn’t the General Secretary. He was made a Lord ultimately – what was it his name was…? Died like two year ago…oh… I can’t remember his name, for the life of me! But any rate, they both sat on the National Joint Council, looking after the interests of that section of their membership who actively pursued their trade within the construction industry, but they had separate negotiating with their own respective employers, the furnishing trades’ employers and the woodcutting machinists’. Yes. So that it would be possible for them to be…perhaps to see their interest really as being separate, distinct, from those of the main building trades. Yeah. Yeah, that seems to… I think they had a similar attitude, what I referred to in the Scottish area, namely that, where my representations on behalf of the granite industry, steel industry, terrazzo industry, was a minority one, they, in turn, with their own individual employers, had a majority interest, in both the furnishing trades’ employers and in the woodcutting machinists’. Yes. Do you feel that there was any pressure from…well, “pressure”…was there any incentive from the part of the NFBTE for the unions to get together? Do you feel that they were anxious to see a consolidation, that they thought it would be useful? Well, I don’t think that the… I think that they were…they were eh…quite keen to do a merger because, so far as they were concerned, they had the same difficulties, namely that there was an overlapping. They were meeting…four representatives, we’ll say, on a given problem, whereas, if there could have been a merger, they could meet one, still speak about and discuss the same subjects. But I wouldn’t say that they took any active part in trying to bring pressures to bear on the unions. I think they would have been wasting their time because they would have been told just where to get off. But I think that they were really…hopeful that such a situation would emerge. Interviewed c.1978 by Janet Druker, then a PhD student at the University of Warwick Interview – John Leonard Transcribed by Alison McPherson, alison.mcpherson@premiertyping.com, www.premiertyping.com Yes. Yes, it was obviously a question, for both sides, of rationalisation of certain kinds of procedures. Yes, yeah, that’s true, and that was what prompted them to bring about the…a merger of their own employers’ side of the two National Joint Councils that were in existence – the National Joint Council and the Scottish National Joint Council. Now, they were able to solve that within their own structures, so far as representation from the Scottish employers was concerned, when it came to the one National Joint Council. Yes. How smoothly do you think the merger went through, altogether? How happy were you with the formation of the one union, of UCATT, after the…? I think it went through quite well. Yeah. I had no…I had no…fears, eh…whilst I was knowledgeable that there would be problems but, in my view, they were not insurmountable. Indeed, it’s been proved that they’ve not been insurmountable because we’ve thrashed them out now. We’ve gone over the five year period, ’71 to ’75, and we see now that there’s a new constitution. There’s been the establishment of a more workable Executive now, with seven representatives, so that these have been…facets that eliminated some of the difficulties, cleared them out the way altogether. Some of the official histories of the building trade unions, I think, you know, the [Hilton] book, “Opposed to Tyranny”, amongst others, suggest that there’s traditionally been a…I don’t know if you’d say antagonism… There’s been perhaps a feeling of almost conflict between the regions and the central organisation of…of all of the building trades’ unions, sort of represented, in one sense, by…with the ASW, for example, by the Managing Committees’ organisation in relation to the Executive. Did you have those kinds of problems within the AUBTW? Do you think that’s a fair assessment? Oh, we had our…we had our problems with our Divisional Councils, as against their Regional Councils, during the AUBTW’s days, but, again, they were…they were not insurmountable. There was antipathy against the Executive in divisions up and down the country, but we overcame them. Then, when the merger took place, eh, it very much became a question then of integrating, within the Regional Councils of the new union, representatives of our old Divisional Councils. So, that, again, went through quite smoothly and with no difficulties at all and has worked fairly well. Again, it was on the basis of pro rata entitlement of representation, as against the other two unions, the Painters and the ASW, related to the membership in that given region. Yes. The scheme for regionalisation was…went through only immediately prior to the merger of the AUBTW, didn’t it? Yes, yeah. Well, that was one thing that didn’t go down too well with the AUBTW because they felt that, in the knowledge that they were discussing a possible merger with us, some of our Executives thought that they should have delayed the regionalisation that they carried through in order to ensure that whatever representation was agreed upon could have been worked into the new regions. But, as you say, they established it before the actual merger became effective. Yes. What exactly did it do in terms of changes in structure? What did it establish? Well, as far as my knowledge serves me, I never made too much…I never made too many enquiries about what it did. It used to be known as the Management Committee, you see. Interviewed c.1978 by Janet Druker, then a PhD student at the University of Warwick Interview – John Leonard Transcribed by Alison McPherson, alison.mcpherson@premiertyping.com, www.premiertyping.com Yeah. The Management Committee, under the old ASW, appeared to me, and I could be wrong, but this was how it appeared to me, to be a law unto themselves in operating as management committees. Now, with the establishment of Regional Councils, it then had the…the effect that Executive representation was…on the regions, from the Executive who represented that particular part of the country, and you were allocated regions on the Executive, you see. The Executive Council allocated Executive members to the various regions. For instance, my regions became the Midlands and the Eastern – that was Birmingham and Cambridge. Others went to London and the South-West and so on. But it meant that there was…three Executive representatives went to region: an ASW man, a painter and a builder. And that really was an attempt then to get over the former problems of division in that it linked the Executive to the localities… Yeah. And of course, we had representatives on the Regional Council from our old Divisional Councils. They were elected in accordance with the numerical strength, so a seat for so-many members. In a way though, with your structure of a lay Executive which came from the regions, you’d never really experienced quite the same problems as the ASW, had you, in that – perhaps you had, but you at least had the basis of an Executive member within his locality, em, and presumably with his sort of local contacts operating in the Divisional Council and so on. Oh yes. Our Executive members sat ex officio on our Divisional Councils. But our Divisional Councils were elected, and, again, they were a part-time Divisional Council, met quarterly, but the structure that we had was that we had a District Committee – first of all, you had the Branch, then you had the District Committee, Divisional Council, and the Executive. That was the three constitutional bodies that the AUBTW had. With the merger, or just prior to the merger, District Committees – and we had thought for a long while that they were…they’d outlived their usefulness really – they disappeared, and we participated in the Regional Councils of the ASW, on the basis of an electoral procedure. The Executive members, as I say, were then allocated by the Executive to the various regions and they sat ex officio as well. Yes. What I was…I don’t know, I was perhaps feeling for, was whether or not you had the...if you like, the differences in policy and attitude between the regions and the Executive within the AUBTW prior to amalgamation, which was experienced certainly in the ASW, and possibly even in the Painters’. Oh, you had the same feelings at divisional level under our own – they were never too happy with the Management Committees of the ASW. They thought that they were…what to say [laughing]…too lackadaisical and no pressing some of the problems that they ought to have been pressing. The other significant difference, I suppose, between the unions that I’m looking at is the question of the Executives, the fact that you’ve got, or had, a lay Executive, as against the Woodworkers and Painters with their full-time Executives, and I wondered really just what their full-time Executives did . I mean, you had National Officers, who presumably had the usual responsibilities of National Officers. What did their additional Executive Committee members who were full-time, based in London, do with themselves on a sort of day-to-day basis? Well, you’re talking about the Executive of the ASW as it…of UCATT now? Yeah. Well, yes, I mean the full-time Executives as a [General Council]. Interviewed c.1978 by Janet Druker, then a PhD student at the University of Warwick Interview – John Leonard Transcribed by Alison McPherson, alison.mcpherson@premiertyping.com, www.premiertyping.com Yeah. Well, the full-time Executive, first of all, they were…it was a question of them appointing their members to the various committees that we were party to. I think the example would be that, in steel, when we became part of UCATT, I was appointed to look after the steel interests. There was an ASW man also appointed to look after the steel industry so far as his members were concerned, because they employ quite a lot. And others were appointed to the Energy Commission and so on and so forth, all these committees, Government committees. Now, between times, he would be doing some work in his own region. He might be seeing the Regional Secretary and doing some work with him. Now, that was the situation with a full-time Executive, but our part-time men, when we were an Executive, all that they did in their respective regions, or divisions rather, was…probably attend branches in the region, in the division, and, once a quarter, attend the Divisional Council, ex officio. That was the difference, but he only did it part-time, as against the man doing it full-time. Yes. I wondered what the…perhaps it’s a question you can’t answer really, but what the Executive of the old ASW did prior to the amalgamation, because they didn’t have a responsibility for a region. No, but they attended their Management Committees as well. Oh, I see. As far as my memory serves me, they certainly attended their Management Committees. Yes. So they still had that… Yeah, they had that contact. I see. It’s another aspect, when you’re talking about trade union structure and mergers externally, it’s always complicated by the internal sort of functions of the union. Oh yes, yes, I agree, yes. Yes, that’s why I’m trying to get to grips with it. That really covers the questions I had. I don’t know if there’s anything you want to add, that you feel was significant in the discussions, in the process of amalgamation…? I don’t think so, no, I don’t think so. No, I think you’ve covered adequately and… It may be, I don’t know – you’ll be the best judge of that – that I’ve probably engaged in some repetition so far as Mr Lowthian is concerned. To some extent, but… Because we were both involved, at some time or other, on the issues. Yes, but obviously, your background in Scotland, and in particular your discussions of the Building & Monumental Workers, you see, he [didn’t mention that]. Oh, that was different from, yes, oh yes, that’s true, yes. So that’s very useful. Anyway, thanks very much! It’s a pleasure. [End of recording]