MS Word Document - 1.5 MB - Department of Environment, Land

advertisement

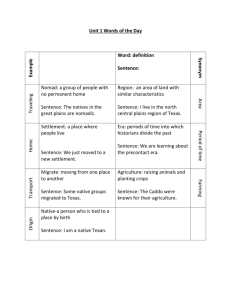

Wellington Mint-bush — the impact of fire on population dynamics at Holey Plains State Park M. Kohout 2011 Arthur Rylah Institute for Environmental Research Technical Report Series No. 219 Wellington Mint-bush – the Impact of Fire on Population Dynamics at Holey Plains State Park Arthur Rylah Institute for Environmental Research Technical Series No. 219 Wellington Mint-bush — the impact of fire on population dynamics at Holey Plains State Park Michele Kohout Arthur Rylah Institute for Environmental Research 123 Brown Street, Heidelberg, Victoria 3084 June 2011 Arthur Rylah Institute for Environmental Research Department of Sustainability and Environment Heidelberg, Victoria Report produced by: Arthur Rylah Institute for Environmental Research Department of Sustainability and Environment PO Box 137 Heidelberg, Victoria 3084 Phone (03) 9450 8600 Website: www.dse.vic.gov.au/ari © State of Victoria, Department of Sustainability and Environment 2011 This publication is copyright. Apart from fair dealing for the purposes of private study, research, criticism or review as permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, no part may be reproduced, copied, transmitted in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical or graphic) without the prior written permission of the State of Victoria, Department of Sustainability and Environment. All requests and enquiries should be directed to the Customer Service Centre, 136 186 or email customer.service@dse.vic.gov.au Citation: Kohout, M. (2011). Wellington Mint-bush – the Impact of Fire on Population Dynamics at Holey Plains State Park. Arthur Rylah Institute for Environmental Research Technical Report Series No. 219. Department of Sustainability and Environment, Heidelberg, Victoria ISSN 1835-3827 (print) ISSN 1835-3835 (online) Disclaimer: This publication may be of assistance to you but the State of Victoria and its employees do not guarantee that the publication is without flaw of any kind or is wholly appropriate for your particular purposes and therefore disclaims all liability for any error, loss or other consequence which may arise from you relying on any information in this publication. Front cover photo: Heavily browsed Prostanthera galbraithiae plant at Holey Plains State Park. (M. Kohout). Authorised by: Victorian Government, Melbourne 2 Contents List of tables and figures ................................................................................................................ iv List of tables ............................................................................................................................iv List of figures ..........................................................................................................................iv Acknowledgements ............................................................................................................................v Summary ............................................................................................................................................1 Recommendations .....................................................................................................................1 1 Introduction .............................................................................................................................2 2 2.1 Methods....................................................................................................................................4 Site description..........................................................................................................................4 2.2 Survey methods .........................................................................................................................4 2.3 Data analysis .............................................................................................................................8 3 3.1 Results ......................................................................................................................................9 Population dynamics and time since last fire ............................................................................9 3.2 Browsing ................................................................................................................................12 4 Discussion .............................................................................................................................15 5 Recommendations ................................................................................................................17 References .......................................................................................................................................18 Appendix 1. Time since last fire of Prostanthera galbraithiae populations at Holey Plains State Park in 2011. .........................................................................................................................19 Appendix 2. Populations of Prostanthera galbraithiae surveyed at Holey Plains State Park in March 2011. ....................................................................................................................................20 3 List of tables and figures List of tables Table 1. Population structure and time since fire for P. galbraithiae at Holey Plains State Park....... 9 Table 2. The proportion of browsed and unbrowsed P. galbraithiae plants at each site .................. 12 List of figures Figure 1. Schematic diagram of how management activities affect population dynamics of P. galbraithiae at Holey Plains State Park (modified from Kohout et al. 2009). The dotted lines show predicted transitions which require further research. .............................................. 3 Figure 2. Locations of Prostanthera galbraithiae populations studied at Holey Plains State Park in March 2011 .............................................................................................................................. 5 Figure 3. The time since last fire of the Prostanthera galbraithiae populations examined at Holey Plains State Park in March 2011. ............................................................................................. 6 Figure 4. Seed capsules of P. galbraithiae in March 2011, retained on the plant approximately....... 7 Figure 5. Measuring the length of new shoots of P. galbraithiae in March 2011. ............................. 7 Figure 6. The relationship between time since last fire and the number of primary stems of P. galbraithiae plants. The Pearson correlation coefficient is shown..................................... 10 Figure 7. The relationship between time since last fire and the mean stem length of P. galbraithiae. The Pearson correlation coefficient is shown. ........................................................................ 10 Figure 8. The relationship between time since last fire and mean new shoot length of P. galbraithiae plants. The Pearson correlation coefficient is shown..................................... 11 Figure 9. The relationship between time since last fire and the number of seed capsules present on P. galbraithiae plants. The Pearson correlation coefficient is shown..................................... 11 Figure 10. Number of primary stems of P. galbraithiae plants at site 8a (fenced and unbrowsed) and site 8b (unfenced and browsed). (mean ± SD) ................................................................. 13 Figure 11. Mean stem length of P. galbraithiae plants at site 8a (fenced and unbrowsed) and site 8b (unfenced and browsed). (mean ± SD) .............................................................................. 13 Figure 12. Mean new shoot length of P. galbraithiae plants at site 8a (fenced and unbrowsed) and site 8b (unfenced and browsed). (mean ± SD)........................................................................ 14 4 Acknowledgements Thanks to Kylie Singleton, Emily Willocks (DSE) and Paula Dower (PV) for assistance in the field. Thanks to Dan Brown (PV) for providing information about the fire history of Holey Plains, Josephine MacHunter for GIS mapping and Fiona Coates for help with design of methods. Michael Duncan, Claire Moxham, Vivienne Turner and David Meagher provided comments on drafts. This project was funded by Statewide Services, Department of Sustainability and Environment, Gippsland. 5 Wellington Mint-bush – the Impact of Fire on Population Dynamics at Holey Plains State Park Summary The perennial shrub Prostanthera galbraithiae (Wellington Mint-bush) is restricted to Holey Plains State Park (SP) and adjacent private property (Dutson Downs) in Victoria. It is classified as nationally vulnerable. Thirty-four populations are currently known from Holey Plains State Park. Browsing by Swamp Wallabies and inappropriate fire regimes are the main threats to the ongoing survival and condition of populations. Prostanthera galbraithiae is an obligate seeder, depending on accumulated soil seed banks for regeneration after adults have been killed by fire. The optimal fire frequency is 10 to 15 years, with a minimum interval of five years. However, browsed populations are likely to have fewer plants reaching reproductive maturity, leading to a much smaller soil seed bank. This will affect both the minimum fire interval and optimal fire frequency for the regeneration of this species. Population dynamics of P. galbraithiae were examined at 14 sites (all browsed except one) with 11 different time intervals since last fire. The population structure of P. galbraithiae varied with time since fire: the proportion of seedlings was highest in the first year after fire, and mature adult plants dominated the population structure by four years after fire. Seedlings also occurred 29 years after the last fire. There was no significant correlation between time since last fire and the number of primary stems, mean stem length, mean new shoot length or the number of seed capsules. Browsing was evident at all unfenced sites. Browsed P. galbraithiae plants had a significantly higher number of primary stems, shorter mean stem length and shorter mean new shoot length compared to unbrowsed (fenced) plants. In addition, browsed plants showed no evidence of seed production. This study has provided two new insights into the ecology of P. galbraithiae. Firstly, long-unburnt areas still support viable populations of the species. Secondly, fire might cue mass germination but some germination from the soil seed bank can occur in the absence of fire. However, with high browsing pressure, the rate of this recruitment is unlikely to be sufficient to maintain P. galbraithiae populations. Recommendations The most important management recommendation for P. galbraithiae is to protect populations from browsing. Without protection from browsing, fire management strategies are unlikely to be effective. In particular: • Plants at site 8b need to be fenced and protected from fire until they have recovered from browsing sufficiently to flower for at least two years. This will enable a soil seed bank to become established. The recovery of this population should be monitored annually for the next three years. • The recently burnt population at site 31a should be fenced to protect germinating seedlings from browsing. • Sites not surveyed since 2005 need to be resurveyed to determine if plants are present. • Unbrowsed Prostanthera galbraithiae populations older than 10 years should be burnt to encourage recruitment from the soil seed bank. A study examining the identity, density, distribution, movement patterns and dietary preferences of the herbivore(s) responsible for browsing P. galbraithiae at Holey Plains SP, particularly in response to fire, would provide specific and targeted information about one of the main threatening processes to the survival of P. galbraithiae. Arthur Rylah Institute for Environmental Research Technical Report Series No. 219 1 Wellington Mint-bush – the Impact of Fire on Population Dynamics at Holey Plains State Park 1 Introduction Prostanthera galbraithiae (Wellington Mint-bush) is a perennial shrub that is vulnerable nationally (Carter and Walsh 2003). It is restricted to Holey Plains State Park (SP) and adjacent private property (Dutson Downs) in south-east Victoria. It grows in heathy open forest, heathland and heathy woodland in the South East Coastal Plain bioregion (Carter and Walsh 2003). Prostanthera galbraithiae is an erect to spreading small shrub that grows 0.3 to 2 m high. It is distinguished from other species of Prostanthera in having stalkless linear leaves and the lower middle petal broader and longer than each of the upper two petals (Conn 1998). It flowers in September to October (Walsh and Entwistle 1999). Surveys conducted in 2004 and 2005 found 34 populations of P. galbraithiae from Holey Plains SP (Trikojus and Reside 2004). These populations ranged in size from one individual to over 1000 plants, and were all close to vehicular tracks because of the method of survey (Trikojus and Reside 2004). Browsing by Swamp Wallabies, inappropriate fire regimes, firebreak slashing and roadworks are the main threats to the survival and condition of populations (Conn 1998, Carter and Walsh 2003, Trikojus and Reside 2004). Of these threats, browsing and inappropriate fire regimes have a significant impact on population dynamics (Kohout et al. 2009). Prostanthera galbraithiae is an obligate seeder, depending on accumulated soil seed banks for regeneration after adults have been killed by fire (Coates and Downe 2007). In the absence of fire, some seed germination occurs from the soil seed bank. Mature individuals decline in vigour after about 10 years (Carter and Walsh 2003), with reduced flowering, and it has been suggested that the optimal fire frequency may be 10 to 15 years (Kohout et al. 2009). Seedlings regenerating after fire can reach reproductive maturity in two years, and the minimum fire interval appears to be about five years in the absence of browsing (Kohout et al. 2009). It is likely that browsing will heavily influence both the minimum fire interval and optimal fire frequency for the regeneration of this species. Browsed populations are likely to have fewer plants reaching reproductive maturity over a longer time (i.e. greater than two years), which will result in a longer time to replenish the soil seed bank compared to unbrowsed populations. The impact of fire and browsing has been investigated in two populations which germinated from soil-stored seed after a prescribed burn in April 2006 (Coates and Downe 2007, Kohout et al. 2009). One of these populations was fenced to protect young plants from wallaby browsing after fire, and the other population was unfenced. In addition, an unburnt and slashed site, and an unburnt site (both browsed) were also investigated. Three years of monitoring showed that there was significant variation in growth and recruitment, attributed to different management regimes. Burning promotes seed germination, while post-fire fencing protects seedlings from browsing and substantially decreases mortality post-fire. Hence, browsing has a significant impact on population size. Figure 1 summarises the impact of fire and browsing on the population dynamics of P. galbraithiae at Holey Plains SP, based on previous studies that examined the interaction between browsing and fire at a small number of sites over five years (Coates and Downe 2007, Kohout et al. 2009). The focus of the study reported here was the more general impact of fire on population dynamics, examining many sites with different time intervals since fire. The aims were to determine: • the time since last fire for each P. galbraithiae population • the relationship between population fecundity and structure with time since fire Arthur Rylah Institute for Environmental Research Technical Report Series No. 219 2 Wellington Mint-bush – the Impact of Fire on Population Dynamics at Holey Plains State Park • the optimal range of age classes of P. galbraithiae populations for inclusion in fire management planning • whether any P. galbraithiae populations require protection from fire • whether any populations require burning. browsing, no fire fire Germination fencing Holey Plains Prostanthera galbraithaie populations Population decline persistant browsing, long-term absence of fire Population increase no plants present fencing, fire no browsing, fire soil seedbank ceases to be present and viable removal of browsing and application of fire no longer effective EXTINCTION Figure 1. Schematic diagram of how management activities affect population dynamics of P. galbraithiae at Holey Plains State Park (modified from Kohout et al. 2009). The dotted lines show predicted transitions which require further research. Arthur Rylah Institute for Environmental Research Technical Report Series No. 219 3 Wellington Mint-bush – the Impact of Fire on Population Dynamics at Holey Plains State Park 2 Methods 2.1 Site description Holey Plains State Park is an area of low sandy hills and undulating plains approximately 10 km south-east of Rosedale in West Gippsland, Victoria. The vegetation is heathy woodland dominated by stringybark and peppermints, including Eucalyptus globoidea, E. consideniana and E. aff. willisii (Gippsland Lakes) on podsol soils. Banksia serrata is a frequent co-dominant. The climate is mild and subhumid (Nicholson 1978). January is the hottest month with a mean maximum temperature of 25.4 °C, and July is the coldest month with a mean maximum temperature of 13.8 °C. Mean annual rainfall is 597 mm, with the most rain falling in November and the least in July (Bureau of Meteorology 2011). 2.2 Survey methods The fire history was estimated by overlaying the current fire mapping of the park with the location of the 34 known P. galbraithiae populations using ArcviewGIS 3.3 (Appendix 1). The populations were prioritised for field surveys by choosing sites with five or more individuals and with a range of time intervals since last fire. Sites with an unknown fire history were classified as ‘50 years since fire’ (i.e. a long time) for the purposes of analysis. Population structure and fecundity were examined at 16 sites with 11 different time intervals since the last fire (Figures 2 and 3) in March 2011. The site numbering follows that of Trikojus and Reside (2004) (Appendix 2). Site 8 consists of a fenced site (8a), unfenced site (8b) and slashed site (8c). A previously unrecorded site was also surveyed (site ‘x’). The location of each site was recorded with a GPS, using GDA 94 coordinates. The location data differed slightly from that given by Trikojus and Reside (2004) because of differences in GPS accuracy. As a consequence, some sites had different actual time intervals since last fire than estimated by mapping (e.g. sites 3, 11, 25, 30, 31a). P. galbraithiae could not be relocated at sites 13 and 23. At each site, up to 20 plants (where this number could be located) were randomly selected and the following variables recorded (following the methods of Kohout et al. 2009): • Presence/absence of browsing. • Developmental stage: 1 = seedling, monopodial (unbranched), 2 = seedling, branched, 3 = mature shrub (reproductive), branched. • Number of primary stems. • Stem length (= plant height, in cm): the mean length of three stems chosen at random, measured from the plant base to living tissue at the stem tip, using a retractable metal tape measure; stems were gently straightened to align with the tape measure. • Number of seed capsules. Seed capsules are retained for about four months after flowering (Figure 4). Counting seed capsules some time after flowering rather than flowers provides a more accurate measure of fecundity since flowers may not always be pollinated successfully. • New shoot length. This extra variable is a measure of current growth. The length (cm) of three randomly selected shoots was measured from the tip of the new shoot to the beginning of woody tissue (Figure 5). Arthur Rylah Institute for Environmental Research Technical Report Series No. 219 4 Wellington Mint-bush – the Impact of Fire on Population Dynamics at Holey Plains State Park N 0 Figure 2. Locations of Prostanthera galbraithiae populations studied at Holey Plains State Park in March 2011. Arthur Rylah Institute for Environmental Research Technical Report Series No. 219 5 1 km Wellington Mint-bush – the Impact of Fire on Population Dynamics at Holey Plains State Park Ú Prostanthera locations 2011 Ê Years since last burnt 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 32 33 36 37 39 40 42 43 44 45 47 71 > 50 Rosedale-Longford Rd N Ê2 Ú Ú3 Ê Ú10 Ê 7ÊÚ Êx Ú 8cÊÚ 8a Ú Ê 8b Ú Ê 9 25 Ú Ê 17 Ê Ú 31a 11 Ú Ê Ú Ê 30ÊÚ Ú14 Ê Ú Ê 15 0 5 Kilometers Figure 3. The time since last fire of the Prostanthera galbraithiae populations examined at Holey Plains State Park in March 2011. Arthur Rylah Institute for Environmental Research Technical Report Series No. 219 6 Wellington Mint-bush – the Impact of Fire on Population Dynamics at Holey Plains State Park Figure 4. Seed capsules of P. galbraithiae in March 2011, retained on the plant approximately four months after flowering. Figure 5. Measuring the length of new shoots of P. galbraithiae in March 2011. Arthur Rylah Institute for Environmental Research Technical Report Series No. 219 7 Wellington Mint-bush – the Impact of Fire on Population Dynamics at Holey Plains State Park 2.3 Data analysis Pearson correlation was used to test the relationship between time since fire and stem length, number of stems, new shoot length and number of seed capsules. Tukey post hoc tests were used to examine the influence of browsing on plant height, number of stems and new shoot length. Results were considered significant if P < 0.05. Analyses were conducted using Mystat 12. Arthur Rylah Institute for Environmental Research Technical Report Series No. 219 8 Wellington Mint-bush – the Impact of Fire on Population Dynamics at Holey Plains State Park 3 Results 3.1 Population dynamics and time since last fire The structure of P. galbraithiae populations varied with time since fire (Table 1). The proportion of seedlings was highest in the first year after fire, while mature adult plants dominated the population structure four years after fire (Table 1). Mature adult plants started declining around 15 years after fire, and seedlings dominated the population structure 29 years after fire (but note that some sites had a very low sample size). There was no significant correlation between time since last fire and the number of primary stems, mean stem length, mean new shoot length, and the number of seed capsules (Figures 6–9). Seed capsules were found on plants at three sites only (sites 7, 8a and 15). Table 1. Population structure and time since fire for P. galbraithiae at Holey Plains State Park. Site 31a 15 9 8a 8b 8c 14 25 2 10 7 17 x 3 11 30a Time since fire (year) 1 4 5 5 5 5 6 8 15 16 18 18 27 29 50 50 Population structure (%) Number of plants surveyed Monopodial seedlings Branched 20 20 20 20 20 20 20 4 11 20 20 5 20 4 4 15 60 5 10 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 5 50 100 20 40 0 15 0 0 0 0 0 9 10 0 40 10 0 0 47 seedlings Arthur Rylah Institute for Environmental Research Technical Report Series No. 219 Mature shrubs 0 95 75 100 100 100 100 100 91 90 100 60 85 50 0 33 9 Wellington Mint-bush – the Impact of Fire on Population Dynamics at Holey Plains State Park 8 Number of primary stems 7 6 R2 = -0.230 5 4 3 2 1 0 0 10 20 30 40 50 60 Time since fire (years) Figure 6. The relationship between time since last fire and the number of primary stems of P. galbraithiae plants. The Pearson correlation coefficient is shown. 180 160 Mean stem length (cm) 140 120 100 R2 = -0.156 80 60 40 20 0 0 10 20 30 40 50 60 Time since fire (years) Figure 7. The relationship between time since last fire and the mean stem length of P. galbraithiae. The Pearson correlation coefficient is shown. Arthur Rylah Institute for Environmental Research Technical Report Series No. 219 10 Wellington Mint-bush – the Impact of Fire on Population Dynamics at Holey Plains State Park 35 Mean new shoot length (cm) 30 25 20 R2 = -0.193 15 10 5 0 0 10 20 30 40 50 60 Time since fire (years) Figure 8. The relationship between time since last fire and mean new shoot length of P. galbraithiae plants. The Pearson correlation coefficient is shown. 120 Number of seed capsules 100 80 60 R2 = -0.202 40 20 0 0 10 20 30 40 50 60 Time since fire (years) Figure 9. The relationship between time since last fire and the number of seed capsules present on P. galbraithiae plants. The Pearson correlation coefficient is shown. Arthur Rylah Institute for Environmental Research Technical Report Series No. 219 11 Wellington Mint-bush – the Impact of Fire on Population Dynamics at Holey Plains State Park 3.2 Browsing Browsing was evident at all sites except the fenced site (8a) (Table 2). Unbrowsed plants were rare, only being recorded at three unfenced sites. These plants were often growing under the protection of other shrubs. The highest proportion of unbrowsed and unfenced plants was at site 31a (all first year seedlings). Table 2. The proportion of browsed and unbrowsed P. galbraithiae plants at each site. Site 2 3 7 8a 8b 8c 9 10 11 14 15 17 25 30 31a x Browsed (%) 100 75 100 0 100 100 100 100 100 100 100 100 100 80 60 100 Unbrowsed (%) 0 25 0 100 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 25 40 0 At site 8, browsed (unfenced) P. galbraithiae plants (site 8b) had a significantly higher number of primary stems, shorter mean stem length and shorter mean new shoot length than unbrowsed (fenced) plants (site 8a) (Figures 10–12). Fenced plants had 104 ± 64 seed capsules, while there was no evidence of flowering and seed production in the unfenced population. Arthur Rylah Institute for Environmental Research Technical Report Series No. 219 12 Wellington Mint-bush – the Impact of Fire on Population Dynamics at Holey Plains State Park Number of primary stems 8 t = -5.017, P < 0.001 6 4 2 0 8a 8b Site Figure 10. Number of primary stems of P. galbraithiae plants at site 8a (fenced and unbrowsed) and site 8b (unfenced and browsed). (mean ± SD). Mean stem length (cm) 250 200 150 t = 5.686, P < 0.001 100 50 0 8a 8b Site Figure 11. Mean stem length of P. galbraithiae plants at site 8a (fenced and unbrowsed) and site 8b (unfenced and browsed). (mean ± SD). Arthur Rylah Institute for Environmental Research Technical Report Series No. 219 13 Wellington Mint-bush – the Impact of Fire on Population Dynamics at Holey Plains State Park Mean new shoot length (cm) 45 40 35 30 t = 6.127, P < 0.001 25 20 15 10 5 0 8a 8b Site Figure 12. Mean new shoot length of P. galbraithiae plants at site 8a (fenced and unbrowsed) and site 8b (unfenced and browsed). (mean ± SD). Arthur Rylah Institute for Environmental Research Technical Report Series No. 219 14 Wellington Mint-bush – the Impact of Fire on Population Dynamics at Holey Plains State Park 4 Discussion Prostanthera galbraithiae is an obligate seeder and responds positively to fire, with large numbers of seedlings germinating after fire. Seedling numbers decrease over time with competition and plants mature into flowering adults within two years after fire (Kohout et al. 2009). Given this response, we may expect an initial decrease in plant numbers after fire, followed by a rapid increase as seedlings germinate. In the presence of browsing, it might be expected that (a) large populations of P. galbraithiae are unlikely to occur and (b) populations are unlikely to be sustainable in the long-term, since browsing prevents plants maturing into flowering adults. In the absence of fire, it would be expected that plants will gradually decline in vigour eventually leading to a decrease in plant numbers. It is unclear whether total loss of above-ground populations will always occur in the long absence of fire. This study has provided two new insights into the ecology of P. galbraithiae. Firstly, fire history mapping across the range of the species at Holey Plains SP has shown that long-unburnt areas still support viable populations of the species, so the need to use fire at regular intervals to maintain the species might not necessarily be supported. It would be worth examining the age of P. galbraithiae plants, as they may not be as ‘old’ as suggested by the fire history. Secondly, this study shows that, although fire might cue mass germination, some germination from the soil seed bank can occur in the absence of fire. However, under high browsing pressure the rate of this recruitment is unlikely to be sufficient to maintain P. galbraithiae populations. This study highlights the necessity for keeping detailed records about fire history. Fire is characterised by many components, including intensity, season of burn and frequency, extent of fires in the landscape (Bond and Keeley 2005). This study is based only on the time since last fire. Of most value to the management of P. galbraithiae would be to examine the effects of fire intensity at Holey Plains SP. Given the potential for some fires to be ‘hot’, because of their timing (in summer) or fuel loads, some evidence is needed that P. galbraithiae seedling recruitment is advantaged by fire per se, or whether it is related to the intensity (i.e. fires that do not heat the soil too much). Germination studies of Prostanthera askania showed that smoke and no heat treatment gave the highest germination response, suggesting that low-intensity fires would be optimal for management of this species (Tierney 2006). Prostanthera galbraithiae may have similar requirements. The lack of a relationship between fire history and the population structure, growth or fecundity of P. galbraithiae was not unexpected given the heavy browsing pressure in Holey Plain SP. Site 8a and 8b clearly demonstrate the impact that browsing can have on a population with the same time since last fire; the fenced plants were significantly taller, had longer new shoots and were flowering compared to unfenced plants, which were shorter, had shorter new shoots and were not flowering. Browsing is not only having a significant negative impact on P. galbraithiae plants, but is also obscuring the (positive) effect that fire can have on a population. Herbivory differs from fire as a disturbance because it applies a more continuous and less intense pressure on a population (Staver et al. 2009). Fire, on the other hand, consumes both living and dead plant material, has broad dietary preferences, but can also be selective (Bond and Keeley 2005). Herbivory has been shown to create a ‘browse trap’ or demographic bottleneck, where plants can be suppressed from becoming reproductive adults (Staver et al. 2009). This is likely to apply to P. galbraithiae at Holey Plains SP, since unfenced seedlings germinating post-fire at site 8 show no sign of flowering compared to those that are fenced. The fence at site 8 will be extended to include previously unfenced seedlings at site 8b in May 2011 (P. Dower, pers. comm.) and it will be interesting to see the response of the plants to release from browsing pressure, in particular the time to flowering. Arthur Rylah Institute for Environmental Research Technical Report Series No. 219 15 Wellington Mint-bush – the Impact of Fire on Population Dynamics at Holey Plains State Park In the case of managing sustainable P. galbraithiae populations, it is vital to understand the impact of fire regime on herbivores. Fire stimulates vegetative regrowth (Gill et al. 1995) and the pattern of burning, size of the area burnt, density and distribution of herbivores and their mobility will then determine the pattern of browsing (Di Stefano 2005). Burnt areas that are small in size tend to act as herbivore ‘sinks’ and attract high numbers of browsers post-fire when vegetation is regenerating. It may be possible to diffuse browsing pressure on P. galbraithiae seedlings in the first few years after fire by burning larger areas in Holey Plains SP. An examination of the movement and habitat selection of herbivores post-fire at Holey Plains would provide an insight into the options for the management of browsing pressure through landscape burn planning. Swamp Wallabies (Wallabia bicolor) are thought to be the main herbivore browsing P. galbraithiae at Holey Plains SP (Carter and Walsh 2003). However, this is based on casual observations and has not been confirmed. Other herbivores may include kangaroos, rabbits, deer, possums and wombats. In order to better understand and manage browsing of P. galbraithiae it is necessary to (a) confirm which species is (or are) responsible for browsing, (b) quantify the browsing pressure and (c) define how much browsing is acceptable, in terms of sustaining P. galbraithiae populations. Herbivore distribution and density might be examined by using a faecal pellet count at a range of sites over a period of time (Di Stefano et al. 2007). This would provide information about whether the pressure is constant throughout the year or seasonal, and if all P. galbraithiae populations experience a similar intensity of browsing. Some previously recorded populations of P. galbraithiae could not be located during this study. This may be because of the limited time available for searching, or because previously recorded plants had died. Small populations are valuable as they are likely to add to the genetic diversity of P. galbraithiae. However, the protection of populations of P. galbraithiae may need to be prioritised, especially where expensive management options are used (e.g. fencing). It may be more cost-effective to protect larger populations first, since they will have a better chance of being sustainable into the future. Arthur Rylah Institute for Environmental Research Technical Report Series No. 219 16 Wellington Mint-bush – the Impact of Fire on Population Dynamics at Holey Plains State Park 5 Recommendations The most important management recommendation for P. galbraithiae is to protect populations from browsing. Without protection from browsing, fire management strategies are unlikely to be effective. In particular: • Plants at site 8b need to be fenced and protected from fire until they have recovered from browsing sufficiently to flower for at least two years. This will enable a soil seed bank to become established. The recovery of this population should be monitored annually for the next 3 years. • The size of the recently burnt population at site 31a needs to be determined and the majority fenced to protect germinating seedlings from browsing. • Sites not surveyed since 2005 need to be re-surveyed to determine if plants are present. In general, any P. galbraithiae populations older than 10 years since last fire could be burnt. However, this will depend on whether plants have been able to flower and create a soil seed bank in the presence of browsing. The maximum longevity or ‘age’ of P. galbraithiae should be determined in order to decide whether populations that are long unburnt have been replacing themselves in the absence of fire. In addition, it would be useful to examine cues for germination in the absence of fire. A study examining the identity, density, distribution, movement patterns and dietary preferences of the herbivore(s) responsible for browsing P. galbraithiae at Holey Plains SP, particularly in response to fire, would provide specific and targeted information about one of the main threatening processes to the survival of P. galbraithiae. Arthur Rylah Institute for Environmental Research Technical Report Series No. 219 17 Wellington Mint-bush – the Impact of Fire on Population Dynamics at Holey Plains State Park References Bond, W.J., and Keeley, J.E. (2005). Fire as a global 'herbivore': the ecology and evolution of flammable ecosystems. Trends in Ecology & Evolution 20: 387-394. Bureau of Meteorology. (2011). www.bom.gov.au/climate/averages. Carter, O., and Walsh, N. (2003). National Recovery Plan for Prostanthera galbraithiae (Wellington Mint-bush) 2004-2008., Department of Sustainability and Environment, Heidelberg, Victoria. Coates, F., and Downe, J. (2007). Population structure of Prostanthera galbraithiae (Wellington Mint-bush) in response to different management regimes at Holey Plains State Park., Arthur Rylah Institute for Environmental Research., Department of Sustainability and Environment, Heidelberg, Victoria. Conn, B.J. (1998). Contributions to the systematics of Prostanthera (Labiatae) in south-eastern Australia. Telopea 7: 319-331. Di Stefano, J. (2005). Mammalian browsing damage in the Mt. Cole State forest, southeastern Australia: analysis of browsing patterns, spatial relationships and browse selection. New Forests 29: 43-61. Di Stefano, J., Anson, J.A., York, A., Greenfield, A., Coulson, G., Berman, A., and Bladen, M. (2007). Interactions between timber harvesting and swamp wallabies (Wallabia bicolor): space use, density and browsing impact. Forest Ecology and Management 253: 128-137. Gill, A., Bradstock, R., Bradstock, R., Auld, T., Keith, D., Kingsford, R., Lunney, D., and Sivertsen, D. (1995). Extinction of biota by fires. Conserving biodiversity: threats and solutions: 309-322. Kohout, M., Coates, F., Hirst, M., and Downe, J. (2009). Wellington Mint Bush - population responses to fire and browsing at Holey Plains State Park., Arthur Rylah Institute for Environmental Research, Melbourne. Nicholson, B.M. (1978). A study of the land in the Gippsland lakes area. Soil Conservation Authority, Victoria. Staver, A.C., Bond, W.J., Stock, W.D., van Rensburg, S.J., and Waldram, M.S. (2009). Browsing and fire interact to suppress tree density in an African savanna. Ecological Applications 19: 1909-1919. Tierney, D.A. (2006). The effect of fire-related germination cues on the germination of a declining forest understorey species. Australian Journal of Botany 54: 297-303. Trikojus, N., and Reside, J. (2004). Distribution and abundance of the Wellington Mint-bush Prostanthera galbraithiae within the Holey Plains State Park. Wildlife Unlimited Consultancy, Bairnsdale. Walsh, N.G., and Entwistle T.J. (1999). Flora of Victoria. Volume 4: Dicotyldedons Cornaceae to Asteraceae. In: Flora of Victoria. Inkata Press, Melbourne. Arthur Rylah Institute for Environmental Research Technical Report Series No. 219 18 Wellington Mint-bush – the Impact of Fire on Population Dynamics at Holey Plains State Park Appendix 1. Time since last fire of Prostanthera galbraithiae populations at Holey Plains State Park in 2011. The year burnt was estimated using GIS to overlay the locations of Prostanthera galbraithiae populations mapped by Trikojus and Reside (2004) on current fire history mapping. Site Easting Northing Year burnt 1 2 3 4 5 6 7a 7b 8a 8b 8c 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29a 29b 30a 30b 31a 31b 32 33 34 490529 490466 492267 492354 492100 492482 492601 493039 495739 496339 496081 497259 489763 490694 489122 489041 488733 488541 495903 495267 494216 494129 494190 495013 495592 489808 488754 488534 488560 493579 492251 493003 492963 489184 489185 496812 496956 494582 496266 496439 5775257 5775105 5775134 5775499 5775026 5774835 5774527 5773826 5773371 5773292 5773351 5773159 5774659 5770896 5769523 5769037 5767214 5766843 5771807 5771549 5772267 5772407 5769783 5768541 5769705 5772350 5771960 5772677 5772851 5770830 5775263 5773785 5773754 5770087 5770136 5771440 5771418 5771449 5769029 5769568 1985 1996 1993 1984 1982 1993 1993 2010 2006 2006 2006 2006 1995 1991 1994 1994 2005 1995 2006 1993 2006 2006 2002 2009 2010 1995 1995 2005 1982 2010 1982 n/a n/a 1994 1994 1993 1993 2010 1966 2010 Years since last fire 26 15 18 27 29 18 18 1 5 5 5 5 16 20 17 17 6 16 5 18 5 5 9 2 1 16 16 6 29 1 29 n/a n/a 17 17 18 18 1 45 1 Arthur Rylah Institute for Environmental Research Technical Report Series No. 219 19 Wellington Mint-bush – the Impact of Fire on Population Dynamics at Holey Plains State Park Appendix 2. Populations of Prostanthera galbraithiae surveyed at Holey Plains State Park in March 2011. Site numbering follows that of Trikojus and Reside (2004). In addition, a previously unrecorded site was surveyed and labelled ‘x’. Site description data are from Trikojus and Reside (2004) and information collected during this study are given. The GPS datum is GDA 94. Site Easting Northing 2 3 7 8a 8b 8c 9 490462 492257 492644 496166 496171 496081 497243 5775095 5775163 5774254 5773296 5773295 5773351 5773141 10 11 489753 490721 5774675 5770898 14 15 488731 488593 5767246 5766868 17 25 495255 488488 5771555 5772528 30 489186 5770082 31a x 496825 492913 5771415 5773909 Site description Crookes Tk, plants in a depression along the track, 150 m south of North Boundary Tk Whites Tk, 15 m west of intersection of Whites Tk and Spring Tk Spring Tk Berlin Wall, fenced Berlin Wall, unfenced Berlin Wall, slashed Berlin Wall, east from site 8 Whites Tk, 200-250 m north of intersection with Hacketts Tk. Population consists of approx 30-50 plants Birmingham Tk On both sides of Jacks Tk, 1.5 km south of Chessum Rd and Jacks Tk intersection South Boundary Tk North side of Chessum Rd surveyed, approx. 10 m from the road Pipeline Tk Jacks Tk, top of the rise, approx. 200 m N of the dam on Box Track. South Pipeline, on south side of the track, ~300 m from Emu Track and Pine Plantation Tk. Spring Tk Arthur Rylah Institute for Environmental Research Technical Report Series No. 219 Year last burnt Years since last fire 1996 1982 1993 2006 2006 2006 2006 15 29 18 5 5 5 5 1995 ? 16 ~50 2005 2007 6 4 1993 2003 18 8 ? ~50 2010 1984 1 27 20 20