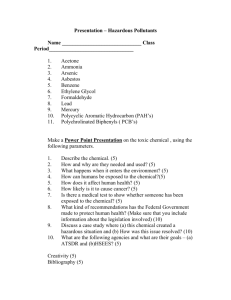

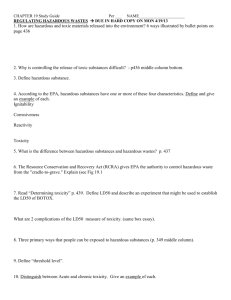

Hazardous waste reform proposal analysis

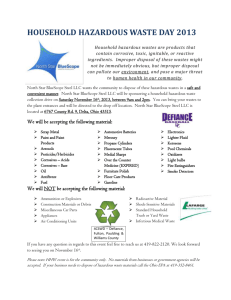

advertisement