ManitouMinimizeFill

advertisement

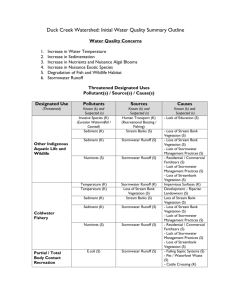

1 Restoration of Ecosystem Services: A Plan to Minimize Filling of Manitou Stream by the Adaptive Restoration Task Force of the UW-Madison Arboretum 12 March 2010 Minimum-grading-and-fill option to fulfill Chapter 30 and the Clean Water Act Negotiated alternative option with an upstream stormwater retention pond, a channel terrace, and Secret Pond unaltered This document is intended to be used in conjunction with the longer, 19 February 2010 version of the Manitou Stream Plan. The longer document contains the context, appendices, and literature cited. 2 Executive Summary Manitou Stream and adjacent wetlands are protected waters of the State and the US, and plans for modification involving filling of waters or wetlands need to be permitted after analysis of alternatives that would avoid, minimize and/or compensate for fill. These protections are consistent with the Arboretum’s stormwater management values and principles. The 635-foot-long Manitou Stream has experienced “urban stream syndrome” (increased stormwater inflows, incised channel, dewatered floodplain, and reduced ecosystem services). Denitrification is especially constrained in urban streams, and Arboretum wetlands are negatively affected because the nitrogen in stormwater stimulates the growth of invasive weeds, especially reed canary grass. Nitrogen can also cause algal blooms in downstream lakes. Ecosystem services could potentially be restored without substantial filling of waters or wetlands and without loss of buried wetland soil. Toward that aim, ARTF proposes a restoration plan that would provide multiple ecosystem services by removing some accumulated sediment along the stream edge, facilitating denitrification on the new floodplain, stabilizing the floodplain and vertical streambanks with coppiced tree willows, and potentially stabilizing the stream bottom. The aim is broad, namely to rehabilitate the area from Manitou Way to Lake Wingra to restore multiple ecosystem services by providing natural landscape features, improving habitat for native plants and animals, accommodating inflowing sediments, reducing eutrophication of Arboretum lands, reducing channel erosion, accumulating sediment where it is needed—in the streambed, where it would elevate the topography and reduce dewatering of the floodplain, thereby enhancing denitrification. In addition, we aim for a holistic system that will attract members of the community to participate in stream rehabilitation and long-term sustainability. Contents 1. Minimum-grading-and-fill option is excerpted from the Plan to fulfill Chapter 30 and the Clean Water Act 2. Negotiated alternative option with an upstream stormwater retention pond, a channel terrace, and Secret Pond unaltered Background Surface-water runoff exceeds historical levels due to hardscape (asphalt, concrete) covering large proportions of urban watersheds, lawns that lack deep-rooted plants, and compacted soils that reduce infiltration. With more runoff and higher peak storm flows, 3 Manitou Stream has experience a suite of conditions known as “urban stream syndrome” involving channel incision and bank erosion, and the adjacent floodplain has experienced lowered water tables, reduced soil moisture, reduced denitrification potential, and conversion of vegetation to plant species that are less flood tolerant than those that might have been present prior to urbanization. The Manitou Stream and its former floodplain is such an example. Manitou Stream The Arboretum’s Adaptive Restoration Task Force (ARTF) considers the channel that carries urban runoff under Manitou Way and into the Arboretum to be an urban stream (herein called Manitou Stream). It has the “urban stream syndrome” (channel incision, bank undercutting, bank sloughing, and erosion of sediments) due to its developed watershed. Stormwater inflows to Secret Pond (modeled to be 513 acre-feet per year) are the largest of all nine inflows to the Arboretum. Manitou Stream flows through 650 feet of incised channel, and the lowest elevation of the streambed occurs within Secret Pond, which has mostly filled in with inflowing sediments. Water flows through Secret Pond and into the marsh downstream, where it is joined by water from the Nakoma Gulf Course Stream and then into Lake Wingra. At the shore of Lake Wingra, sediment from one or both streams accumulates and forms islands that gradually become vegetated. ARTF has designed a water-quality monitoring program to evaluate particulate and dissolved materials that are of concern to managers of the Arboretum and Lake Wingra, e.g. phosphorus and nitrogen, which stimulate weed invasions in Arboretum wetlands (Green and Galatowitsch 2002, Boers and Zedler 2008, Kercher et al. 2007) and cause eutrophication, leading to algal blooms (Lathrop 2007, Carpenter 2008, Lewis and Wurtzbaugh 2009). An important role for UW The University could play a unique role in demonstrating how best to manage stormwater. Others look to UW for leadership in multi-disciplinary policy/decision making and innovation in technology and conservation. They look to the Arboretum for leadership in restoration and land care. The need to improve stormwater facilities within the Arboretum provides many opportunities for innovation, research, and education.. Note that biological systems are inherently complex, and detailed predictions are always challenged by unknowns. There are several unknowns in the in the stormwater management arena and for stormwater treatment options. Other unknowns have been identified for the “Best Management Practice” of creating a large stormwater retention basin, e.g. therole of impoundments as habitat for mosquitoes (Irwin et al. 2008), “magnets for invasive species” and “stepping stones” for the dispersal of invasive species from those impoundments to natural lakes and ponds (Johnson et al. 2008. The Arboretum follows an innovative adaptive restoration approach for situations where there is insufficient knowledge to guarantee outcomes of alternatives. 1. Minimum-grading-and-fill option to fulfill Chapter 30 and the Clean Water Act 4 Ecosystem services are ecological functions that are valued by society. Wetlands (including shallow waters to 6 m depth, as defined by the Ramsar Convention [international treaty]) provide disproportionate levels of annually renewable ecosystem services. Using data of Costanza (1995), wetlands covering 1.5% of the earth contribute 40% of ecosystem services globally—26 times the per-area contribution from uplands and oceans. Goal: The Arboretum needs to fulfill its mission (to conserve and restore the land, advance restoration ecology, and foster the land ethic) as well as comply with stormwater regulatory requirements. The aim is broad, namely to rehabilitate the area from Manitou Way to Lake Wingra to restore multiple ecosystem services by providing natural landscape features, improving habitat for native plants and animals, accommodating inflowing sediments, reducing eutrophication of Arboretum lands, reducing channel erosion, accumulating sediment where it is needed—in the streambed, where it would elevate the topography and reduce dewatering of the floodplain, thereby enhancing denitrification. In addition, we aim for a holistic system that will attract members of the community to participate in stream rehabilitation and long-term sustainability. This Restoration Alternative would create conditions to support ecosystem services associated with historical streams, their adjacent floodplains and wetlands, without filling wetlands or waters of the US. Why not a focus on restoring historical vegetation? Given that Manitou Stream carries water that is greater in volume and lower in quality than occurred naturally, and given that the land adjacent to the stream has accumulated tons of sediment overlying its wetland soil, historical conditions could only be restored with heroic efforts to replumb the watershed, then excavate and transport sediments off-site. In addition, the Arboretum is required to maintain a specific one-acre stormwater retention facility, namely, Secret Pond, which is a novel landscape feature. Novel approaches for transforming degraded and altered landscapes recognize the dynamic nature of both restored and reference ecosystems, as well as the need to address both structure and functioning (Ewel and Putz 2004, Suding, Gross and Houseman 2004, Harris et al. 2006, Zedler 2009, Seastedt, Hobbs and Suding 2008, Jones and Monaco 2009). Why a focus on ecosystem services? A principal reason for focusing on functions instead of specific plant or animal species is the high value and importance of ecosystem services to downstream ecosystems. A feasible goal is to restore ecosystem services that have been lost within the watershed; thse include phosphorus- and sediment-removal services, as well as floodplain habitat, denitrification, and cultural services. Ecosystem services that are especially needed are: 5 • Reduction of nitrogen loading to Arboretum wetlands and Lake Wingra • Reduction of phosphorus loading to Arboretum wetlands and Lake Wingra • Erosion control • Reduction of floodplain dewatering • Biodiversity support • Resistance to invasive plants Location: Existing stream and adjacent wetland and upland between Manitou Way and Secret Pond (the existing stormwater retention pond that is filled with sediment), with consideration of additional ecosystem services occurring within Wingra Marsh and along the Lake Wingra shore. Arboretum lands at this site include the Manitou Stream, its riparian woodland, west Wingra Marsh, and the shore of Lake Wingra. Manitou Stream has a lower, 350-ft stream segment and an upper 285-ft stream reach that would be supplanted by a 2.43-acre stormwater retention basin in other alternatives designed by Strand Engineering. The total length of the stream, from Manitou Way to Secret Pond is 635 feet. An estimate of the proposed restoration project footprint is 0.84 acres. This would include 0.84 acres of proposed floodplain restoration and 0.30 acres of existing sream bottom, i.e., 0.54 acres. Historical sediment delivery: The study experienced major sedimentation in past decades, followed by lowering of the water table (Pathak 2009). Soil profiles nearest the stream indicate that 27-48 inches of recent soil overlies a buried organic soil just north of the existing stream (Table 1). Substantially more data on the depth to organic soil are needed to develop a plan to remove accumulated sediments and not disturb the underlying wetland soil. We recommend 10 transects from each stream edge inland to the limit of proposed excavation, with 1-inch cores taken at 2- to 5-m intervals along each transect, assessing depth to organic soil. Table 1. Depth of sediment overlying organic soil at west Wingra Marsh (from Pathak 2009). Well number Depth of surface sediment (inches) North of stream 1 2 8 9 30 27.5 48 27 South of stream 14 15 23 0-12 0-13 0-12 6 Figure 1. Current vegetation as mapped by Pathak (2009). Recommended actions to restore ecosystem services • Open the canopy along the stream course to increase light (to enhance willow growth) • Partially remove sediment that overlies the buried wetland soil • Promote denitrification on the floodplain • Stabilize the floodplain sediments with roots (tree willows planted on the floodplain) • Coppice the tree willows to avoid windthrows; remove biomass when P content is high. • Stabilize the streambanks and streambed edge with sandbar willows • Consider widening the thalweg to accommodate roughness due to sandbar willow • Stabilize stream bottom sediments with fieldstone crossings • Allow sediments to accumulate and elevate the streambed to slow floodplain dewatering; allow phosphorus to be stored in the stabilized sediment • Excavate most accumulated sediment in Secret Pond • Retain the vegetated island at the mouth of the stream in L. Wingra • Provide cultural services, including uses of harvested willow twigs and poles. We propose to advance restoration ecology by incorporating small experiments into the plan to test the use of native willows in stabilizing the floodplain (e.g., varying planting density and coppicing frequency), shallow pools of varied size to remove nitrogen, and sandbar willow to stabilize the streambanks and streambed edges. The science/practice of “adaptive restoration” is also advanced by initiating field experiments that provide guidance for subsequent restoration efforts. Field tests of understory plantings would also be possible on the floodplain. Studies of soil stabilization, 7 stormwater infiltration, arthropod use, bird use, and biofuel production could also be supported by the following restoration project. Figure 2. The 0.84 project footprint above Secret Pond. Areas include the 0.30-acre stream bottom (of which 0.12 ac are in the upstream segment and 0.18 ac are in the downstream segment). The upstream segment is the portion that would be covered by a stormwater retention basin in alternatives designed by Strand Engineering. Figure 3. Cross-section for Manitou Stream showing recently-deposited sediment to be removed, underlying buried wetland soil to be conserved, willow posts to be planted on the resulting floodplain, and willow poles to be planted in segments of the stream. Depressions that would pond water after overbank flooding are not shown in these cross-sections. This alternative has willows on a graded south-facing streambank and a widened streambed (width not determined), Fieldstone crossings about every 60 linear feet are under discussion. Illustrations by M. Wegener. 8 Figure 4. Overview possible floodplain alongside Manitou Stream, showing a widened streambed (crudely estimated), a sloped north side of stream with sandbar willow plantings to stabilize the bank, with the south bank left intact. Illustration by Mark Wegener, with input from Jim Doherty and Brad Herrick. 9 Explanation of each action Opening the canopy to increase light. Prior to excavation, trees would be selected by ARTF for removal in each 18-ft-wide strip along Manitou Stream. Additional trees would be removed on the south side of the stream to open the canopy and increase light to enhance willow growth. Removal would be selective in order to retain heritage trees or trees considered important for ecosystem services, such as soilholding capacity. Partial sediment removal: We propose to remove existing trees along a narrow strip next to Manitou Stream and then to remove some of the sediment that has accumulated over decades, leaving 12 inches above the buried wetland soil. While a large area could be deforested and graded, costs will likely limit the effort. The area of sediment removal could be under 0.5 acres. It could be evenly divided to two 15 x 600-ft strips, one to the north and one to the south of Manitou Stream. Assuming an average depth of removal of 1 foot, the volume of sediment to move could be 0.5 acre-feet (807 cubic yards for the smaller estimate). The remaining streambank will be left intact; i.e., it will not be graded. Note: ARTF still needs to consider the regulations about grading and the permits needed. Promoting denitrification on the floodplain: Floodplain contouring would support diverse understory vegetation and trap overbank flows in shallow ponds. Providing a variety of sizes and depths of depressions will allow pools to develop following stormwater pulses with overbank flooding. These pools are intended to provide the valued functions of unfiltration and denitrification. The principal factors that promote denitrification are moisture (enough to create anaerobic conditions) and root biomass (which provides organic matter to the rhizosphere, where microbes use it as food during denitrification). Fine-textured soil (silt and clay) on the floodplain helps to retain soil moisture (Pinay et al. 2000). Shallow pools and an understory of native plants known to produce both shallow and deep roots (Botany 670 experimentation) will promote conditions that enhance denitrification potential in restored urban streams (Gift et al. 2010). Soil probes would be used to identify depth to organic soil so that the volume and location of excavation can be estimated. Streambank and floodplain stabilization: Tree-willow posts will be established on the excavated floodplain to stabilize the floodplain soil (see also Barendregt et al. 2009). Herbaceous understory plantings of native species known to provide ecosystem services would further reduce erosion, assist in infiltration and resist invasion by wetland weeds. Suitable species to plant and planting approaches are described in appendices. Note that black willow occurs north of Secret Pond (B. Herrick, from Botany 455 class data). Willow post densities will be established at two levels in an experimental framework. Streambanks will be stabilized in part by roots that will grow from willow poles or posts installed along the stream channel on the floodplain. In addition, sandbar willow stakes will be placed within the banks as described after coppicing. Herbaceous vegetation will be provided to enhance infiltration (and denitrification), reduce soil erosion, and resist weed invasion. Herbaceous understory 10 species suitable for seed mixes (described in future appendices). Note that willow plantings might also reduce reed canary grass invasion (Kim et al. 2006). Streambed stabilization: Manitou Stream is subject to pulses of stormwater that can flow up to a maximum of 300 cubic feet per second (cfs), limited by the size of the culvert under Manitou Way. Down-cutting of the outfall at Manitou Way is reduced by riprap and boulders that were recently put in place within the Arboretum. Further downcutting along the entire Manitou Stream (and resulting undercutting of stream banks) could be abated using willow plantings, fieldstone crossings, and/or large woody debris. Large woody debris is a common stream restoration practice, and it is particularly valued for its ability to provide habitat for macroinvertebrates (Miller et al. 2010). Because large trees will be removed along the edges of Manitou Stream, there will be opportunity to place trunks in the stream strategically to achieve such functions. More study of the extensive literature on ecosystem services provided by various uses of large woody debris is needed to develop specific plans for such addition. Fieldstone crossings would be used to divide Manitou Stream into six to ten stream reaches. Large stones could be placed across the stream as in the Pike Creek project in a Minneapolis suburb (MacDonagh and Ryan 2009). Pike Creek statistics are quite similar to those of Manitou Stream. For Pike Creek, the watershed area = 465 acres, impervious surfaces = 35-50%, project length = 1,600 feet, project width = <120 feet, maximum bank depth = <8 feet, maximum water depth = <7 feet, width = 10-12 feet, soils along channel = Hamel Loam and Heyder Sandy Loam, channel gradient = 1.5%, flow range = 0-800 cfs, maximum velocity = <9 fps (from MacDonagh and Ryan 2009). If 6-10 stream crossings (one per 60-ft or 100-ft stream reach) are established (each crossing @ 3 x 10 ft. = 30 sq. ft.), the area of fieldstone fill will total 180 sq. ft. for 5 crossings (6 segments) or 270 sq. ft. for 9 crossings (10 segments). Adding sandbar willows along the streambank edges within the fieldstones would anchor the fieldstones. Sediment erosion or accretion will be assessed and test plots expanded or replanted accordingly. The plantings are described in detail below. Sandbar willow stakes would be inserted into both streambanks along the entire stream, using standard staking approaches. Willows will be planted in a pilot phase, followed by later plantings, based on earlier results. If plantings are done prior to a rain storm and streamflow pulse, it is possible that the poles that have not established solid rooting will wash out, even though sandbar willows are known for their flexibility (Alice Thompson, pers. comm. 2009). ARTF is prepared to reestablish sandbar willow plots if poles need to be replaced. Curtis Prairie has an overabundance of sandbar willows, and poles are easily harvested and relocated. Maintaining Secret Pond: DNR regulations require that existing stormwater facilities be maintained. Secret Pond has accumulated substantial sediment, although the stream continues through it and discharges into a cattail marsh. The downstream portion of Secret Pond still holds water and supports native wetland vegetation, including arrowhead, rice-cut grass and common bur-reed (2006 survey by Steven Hall). This wetland vegetation likely filters surface water flow and potentially reduces transport of TSS to Lake Wingra. 11 The constructed volume of the pond is not known, but if estimated to be an acrefoot, around 1600 cubic yards of accumulated sediment would need to be excavated. Removing accumulated sediment would be done in winter, to reduce impacts on soil and vegetation. Sediment will be moved off-site to prevent re-release of contaminants and to avoid construction of mounds or berms elsewhere on-site. The northeastern tip of the pond should be left intact, as it is still functions as a wetland with native vegetation. Prior to excavation, historical records of the depth and location of the excavation for Secret Pond will be consulted and not exceeded in removing the accumulated sediment. Care will be taken to leave the pond bottom and edges sealed where they abut wetland soil so that underlying peat is not disturbed or removed. To stabilize the disturbed banks, sandbar willow plantings would be extended from Manitou Stream around the edges of the excavated portion of Secret Pond. ARTF recommends that accumulated sediments be excavated during winter to reduce impacts of heavy equipment on the adjacent wetland soil and vegetation. Providing cultural services: Research, education, and passive recreation will be promoted by experimental willow plantings and depressions on the floodplain (see following section). ARTF envisions that local neighbors and Friends of the Arboretum might adopt segments of the restored stream for restoration and maintenance. The “Adopt-a-StreamReach” program could attract donations for fieldstones, volunteers to install sandbar willows, volunteers to monitor establishment and growth of willows, volunteers to harvest willow twigs and poles, and volunteers to assist with research. Passive recreation (bird watching, hiking) would be facilitated by trails that would also be used by those who coppice the tree willows. Trails are inevitable, so it would be prudent to establish routes that will benefit project maintenance. To reduce liability issues, signs will be placed to keep visitors on trail, cautioning that fieldstones are slippery, rapidly-flowing streams are dangerous, and wetland soil can trap boots. Planning for new signage would benefit from public involvement (Figure 8). “Foster Parents” of the adopted stream reaches could post their activities and contributors and use signs to keep track of areas restored and ecosystem services provided. They could also contribute news and data to the Arboretum’s interactive web site. 2. Negotiated alternative option with upstream stormwater retention pond, channel terrace, and Secret Pond unaltered The above Restoration Plan would not generate stormwater credits for the municipalities who have helped fund other stormwater retention basins in the Arboretum. Here, we consider the trade-off of combining a stormwater retention pond upstream of a restored stream. This option would not avoid filling caused by the installation of an inline pond, because the berm would cross Manitou Stream, and sediments would accumulate inside the berm and fill the existing stream channel. Previously, Strand Engineering designed a 2.43 stormwater retention basin for Manitou Way that also calls for complete grading of the banks of Manitou Stream with turf-reinforcement matting for the remaining 300 ft of Manitou Stream, amounting to additional fill. In addition, Secret 12 Pond is excavated but bank stabilization measures are uncertain. Collectively, their pond and stream projects greatly exceed 10,000 sq. ft. of grading and filling. Permitting issues need to be considered. If a pond is agreed upon and permitted, there are still opportunities to minimize filling in Manitou Stream downstream of the pond. Instead of armoring the 300 ft length of streambanks, ARTF recommends a downscaled version of the above Restoration Alternative, to learn how willows can stabilize streambanks and streambed edges. ARTF recommends avoiding or minimizing changes to Secret Pond in exchange for accepting a conventional stormwater retention pond at Manitou Way. Presumably, this would involve a variance from DNR to leave some sediment in place in Secret Pond, in order to allow a shallow-pond system to support wetland vegetation and improve water quality. We would plan to use willows to stabilize the banks of any grading in or around Secret Pond. Employing the stream restoration in an adaptive manner would allow ARTF to test effectiveness of willows in streambank and pondbank stabilization before full-scale implementation of the combined pond/stream modifications. The decision-making process ARTF recommends improving the process of achieving consensus. The Stormwater Committee should be apprised of regulatory constraints, allowed to hear a description of this plan, and be given ample opportunity to understand multiple viewpoints to discuss alternatives face-to-face. If consensus is not achieved, multiple viewpoints and rationales should be presented to the Arboretum Committee. The Arboretum Committee should understand the requirements for permitting, acknowledge the potentially conflicting regulations and agreements, and objectively weigh the pros and cons of alternative plans. The Arboretum Committee should be asked to provide a policy statement on the relative merits of alternatives that avoid, minimize and compensate for negative impacts to Arboretum lands. They would need to read this plan to obtain essential background information. Initial discussion with Cami Peterson regarding project permitting should include all alternatives, along with analysis showing plans to avoid, minimize or compensate for filling. The Arboretum Director should be included in that discussion. ARTF should contribute to the alternatives analysis and sign off on content. ARTF representatives should work closely with Strand Engineering in writing specifications for implementing features described herein to ensure that they are consistent with Arboretum goals, objectives, values, and principles. All concerned need to know how many credits the Arboretum has agreed to provide the City in total and how many stormwater-treatment credits would be derived from each alternative at Manitou Way. This knowledge would improve the overall process and assist in future planning that has been scheduled for Arboretum lands. It is specifically essential that the Arboretum know how stormwater treatment credits obtained (or not obtained) at Manitou Way would affect the stormwater credits that would be provide in Curtis Prairie. 13