Complications of urinary bladder catheters and preventive strategies

Author

Anthony J Schaeffer, MD

Section Editor

Jerome P Richie, MD, FACS

Deputy Editor

Kathryn A Collins, MD, PhD, FACS

Disclosures

All topics are updated as new evidence becomes available and our peer review process is

complete.

Literature review current through: May 2012. | This topic last updated: Abr 27, 2012.

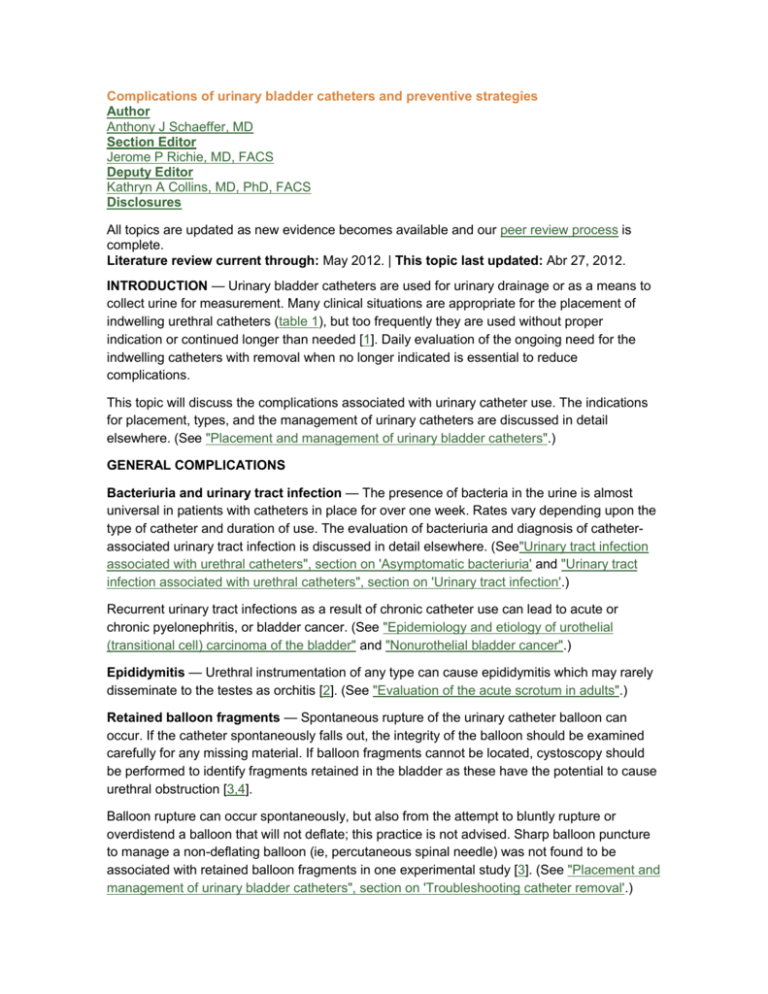

INTRODUCTION — Urinary bladder catheters are used for urinary drainage or as a means to

collect urine for measurement. Many clinical situations are appropriate for the placement of

indwelling urethral catheters (table 1), but too frequently they are used without proper

indication or continued longer than needed [1]. Daily evaluation of the ongoing need for the

indwelling catheters with removal when no longer indicated is essential to reduce

complications.

This topic will discuss the complications associated with urinary catheter use. The indications

for placement, types, and the management of urinary catheters are discussed in detail

elsewhere. (See "Placement and management of urinary bladder catheters".)

GENERAL COMPLICATIONS

Bacteriuria and urinary tract infection — The presence of bacteria in the urine is almost

universal in patients with catheters in place for over one week. Rates vary depending upon the

type of catheter and duration of use. The evaluation of bacteriuria and diagnosis of catheterassociated urinary tract infection is discussed in detail elsewhere. (See"Urinary tract infection

associated with urethral catheters", section on 'Asymptomatic bacteriuria' and "Urinary tract

infection associated with urethral catheters", section on 'Urinary tract infection'.)

Recurrent urinary tract infections as a result of chronic catheter use can lead to acute or

chronic pyelonephritis, or bladder cancer. (See "Epidemiology and etiology of urothelial

(transitional cell) carcinoma of the bladder" and "Nonurothelial bladder cancer".)

Epididymitis — Urethral instrumentation of any type can cause epididymitis which may rarely

disseminate to the testes as orchitis [2]. (See "Evaluation of the acute scrotum in adults".)

Retained balloon fragments — Spontaneous rupture of the urinary catheter balloon can

occur. If the catheter spontaneously falls out, the integrity of the balloon should be examined

carefully for any missing material. If balloon fragments cannot be located, cystoscopy should

be performed to identify fragments retained in the bladder as these have the potential to cause

urethral obstruction [3,4].

Balloon rupture can occur spontaneously, but also from the attempt to bluntly rupture or

overdistend a balloon that will not deflate; this practice is not advised. Sharp balloon puncture

to manage a non-deflating balloon (ie, percutaneous spinal needle) was not found to be

associated with retained balloon fragments in one experimental study [3]. (See "Placement and

management of urinary bladder catheters", section on 'Troubleshooting catheter removal'.)

Bladder fistula — The presence of air or feces in the urine of a patient with an indwelling

catheter may indicate the formation of a fistula. Fistulas can occur between the bladder and

small intestine, colon, rectum, or vagina (ie, enterovesical, colovesical, rectovesical, and

vesicovaginal). They are an uncommon complication of indwelling bladder catheters and more

likely to occur in the setting of prolonged catheterization with risk factors that include

malignancy, inflammation, radiotherapy or trauma [5].

Bladder perforation — Bladder perforation, both intraperitoneal and extraperitoneal, is rare

but has been reported with long-term indwelling catheters [6-8]. Hematuria and abdominal pain

may indicate acute perforation; free air is seen only with intraperitoneal perforation.

Bladder stone formation — Stones can form in the bladder due to the presence of a foreign

body. Bacteria that are urea-splitting (ie, Proteus mirabilis) are frequently associated with stone

formation. The type of catheter may influence stone formation; however, there are no data to

support the use of one catheter material (ie, latex, silicon) over another.

COMPLICATIONS SPECIFIC TO TYPE OF CATHETER

Condom catheters — Most complications related to condom catheter usage are due to

improper or prolonged application, and inadequate monitoring of the device when in place.

Most complications are minor and self limited; however, significant penile injury resulting in

scarring and deformity can occur.

Patients with penile skin sensory loss (ie, spinal injury patients) are at the highest risk for more

severe complications [9]. Instruction of the patient, relatives, and medical personnel on the

proper application of the condom device is essential in preventing associated complications.

(See "Placement and management of urinary bladder catheters", section on 'External catheter

placement'.)

Pressure effects — Skin depigmentation can occur but is more likely in patients with

underlying dermatologic conditions. (See "Vitiligo".)

Constrictive effects of the condom catheter's adhesive band or roller ring can lead to superficial

ulceration. Reapplication exacerbates the ulcer and can prevent healing. The condom catheter

should be temporarily discontinued and a catheter (intermittent or indwelling) used until the site

is healed.

Prolonged continuous pressure of the penis from an improperly placed condom catheter can

cause tissue ischemia which may lead to penile and/or urethral necrosis. Treatment with

surgical debridement is necessary to remove devitalized tissue, and reconstruction with skin

grafts to the penis may be required.

Urethral catheters — Mechanical catheter problems such as leakage, blockage, and catheter

rejection can frustrate and annoy both patient and clinician [10]. Knowledge of catheter

technology and routine catheter care can help reduce mechanical problems. (See "Placement

and management of urinary bladder catheters", section on 'Catheter

technology' and "Placement and management of urinary bladder catheters", section on

'Catheter care'.)

Effects of urethral trauma — Traumatic urethral catheter placement can lead to urethral

injury. The presence of pain and bleeding following attempted catheter insertion, and

subsequent inability to pass the catheter into the bladder suggests that a false urethral

passage may have been created. Such injuries usually require significant reconstructive

surgery.

Inflammation and infection of the periurethral soft tissues may create an abscess as a

consequence of the creation of a false passage [11]. If the abscess is not visible on physical

examination, diagnosis may be delayed and the infection can spread into surrounding tissues.

Urethrocutaneous fistulae may result as the infection tracks to the skin. Fournier's gangrene

has been reported as a consequence of urethral catheterization [12]. (See "Necrotizing soft

tissue infections" and "Evaluation of the acute scrotum in adults".)

Stricture associated with urethral catheterization occurs almost exclusively in male patients

[11]. Repeated urethral trauma from intermittent catheterization can cause urethral stricture

formation, which in turn increases the likelihood of traumatic catheterization. The incidence of

urethral stricture increases with duration of chronic catheterization; most have developed

following at least five years of intermittent catheterization (IC) [13,14].

A retrospective review found urethral stricture in 3.7 percent of 230 men with a history of

indwelling catheter usage; chronic changes of the urethra were documented in nearly one-third

of the patients [15].

Incontinence — Incontinence can occur due to catheterization and is also related to urethral

sphincter dysfunction. (See "Clinical presentation and diagnosis of urinary incontinence".)

Suprapubic catheters — When performed properly, complications from suprapubic catheter

placement are uncommon. Complications associated with initial placement include cutaneous

or bladder bleeding and bowel injury, which is more common if suprapubic catheter placement

is attempted when the bladder is not fully distended [16].

Long-term complications include skin erosion and problems with chronic leakage.

PREVENTION OF COMPLICATIONS — Appropriate urinary catheter implementation and

management can reduce the incidence of complications. The most effective strategies to

reduce infectious complications of urinary catheters are avoidance of unnecessary

catheterization, and catheter removal when the catheter is no longer indicated. Adherence to a

protocol for indwelling catheter placement, care, and removal can reduce the incidence of

urinary tract infection and other complications [1,17].

Measures which help prevent complications associated with urinary catheters include:

Use of urinary catheters only for appropriate indications (table 1). (See "Placement and

management of urinary bladder catheters", section on 'Indications for catheterization'.)

Considering alternatives to indwelling urethral catheters. (See "Placement and

management of urinary bladder catheters", section on 'Choice of catheter'.)

Provision of adequate training to medical staff, patients, and other caregivers on

catheter placement and management. (See "Placement and management of urinary

bladder catheters".)

Removal of catheters when no longer indicated. (See "Placement and management of

urinary bladder catheters", section on 'Catheter care'.)

Not routinely replacing urethral catheters. (See "Placement and management of urinary

bladder catheters", section on 'Catheter care'.)

Specific measures to prevent catheter-associated urinary tract infection include:

Using a continuously closed drainage system. (See "Placement and management of

urinary bladder catheters", section on 'Catheter technology'.)

Not routinely irrigating catheters; catheters are irrigated only under select

circumstances. (See "Placement and management of urinary bladder catheters",

section on 'Catheter care'.)

SUMMARY AND RECOMMENDATIONS

The most effective strategy to reduce complications of urinary bladder catheters is the

avoidance of unnecessary catheterization. When urinary bladder catheters are

required, adequate training of the patient, hospital personnel, and caregivers is

essential to avoid complications related to placement, ensure proper care, and to

promptly recognize and treat complications expeditiously when they do occur.

(See 'Prevention of complications' above.)

The most common complication of urinary bladder catheters is catheter-associated

urinary tract infection. In males, urinary infection can lead to epididymitis or orchitis.

Other rare complications of indwelling catheters include urinary tract obstruction from

retained balloon fragments, bladder fistula, bladder perforation, or bladder stone

formation. (See 'General complications' above.)

Improper or prolonged application of condom catheters can cause pressure-related

complications including skin depigmentation, ulceration, or penile necrosis. These

complications are more frequent in patients with penile sensory loss and can be

prevented with proper application of the device and frequent patient monitoring.

(See 'Condom catheters' above.)

The traumatic insertion of urethral catheters can create a false passage which may, if

infected, lead to periurethral abscess. This complication is more frequent in patients

with prior urethral stricture and can result in significant soft tissue infection.

(See 'Effects of urethral trauma' above.)

Long-term complications associated with chronic urethral catheters (indwelling or

intermittent) include urethral stricture and incontinence (see 'Urethral catheters' above).

When properly placed, complications from the placement of suprapubic catheters are

uncommon. Inadvertent bowel injury can occur during percutaneous suprapubic

catheter placement if the bladder is not fully distended, or the needle is not visualized

with cystoscopy when performing the procedure in patients with prior pelvic surgery.

(See 'Suprapubic catheters' above.)

Use of UpToDate is subject to the Subscription and License Agreement.

REFERENCES

1. Hooten, TM, Bradley, SF, Cardenas, DD, et al. Diagnosis, prevention and Treatment of

Catheter-Associated Urinary Tract Infection in Adults: 2009 International Clinical Practice

Guidelines from the Infectious Diseases Society. Clinical Infectious Diseases 2010; 50:625.

2. Igawa Y, Wyndaele JJ, Nishizawa O. Catheterization: possible complications and their

prevention and treatment. Int J Urol 2008; 15:481.

3. Gülmez I, Ekmekcioglu O, Karacagil M. A comparison of various methods to burst Foley

catheter balloons and the risk of free-fragment formation. Br J Urol 1996; 77:716.

4. Daneshmand S, Youssefzadeh D, Skinner EC. Review of techniques to remove a Foley

catheter when the balloon does not deflate. Urology 2002; 59:127.

5. Hawary, A, Clarke, L, Taylor, A, et al. Enterovesical fistula: a rare complication of urethral

catheterization. Adv Urol 2009; 59:1204.

6. Merguerian PA, Erturk E, Hulbert WC Jr, et al. Peritonitis and abdominal free air due to

intraperitoneal bladder perforation associated with indwelling urethral catheter drainage. J Urol

1985; 134:747.

7. Farraye MJ, Seaberg D. Indwelling foley catheter causing extraperitoneal bladder perforation.

Am J Emerg Med 2000; 18:497.

8. Spees EK, O'Mara C, Murphy JB, et al. Unsuspected intraperitoneal perforation of the urinary

bladder as an iatrogenic disorder. Surgery 1981; 89:224.

9. Jayachandran S, Mooppan UM, Kim H. Complications from external (condom) urinary drainage

devices. Urology 1985; 25:31.

10. Belfield PW. Urinary catheters. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed) 1988; 296:836.

11. Pannek J, Göcking K, Bersch U. Perineal abscess formation as a complication of intermittent

self-catheterization. Spinal Cord 2008; 46:527.

12. Conn IG, Lewi HJ. Fournier's gangrene of the scrotum following traumatic urethral

catheterisation. J R Coll Surg Edinb 1987; 32:182.

13. Wyndaele JJ, Maes D. Clean intermittent self-catheterization: a 12-year followup. J Urol 1990;

143:906.

14. Perrouin-Verbe B, Labat JJ, Richard I, et al. Clean intermittent catheterisation from the acute

period in spinal cord injury patients. Long term evaluation of urethral and genital tolerance.

Paraplegia 1995; 33:619.

15. Gunther, M, Lochne, ED, Kramer, G, Stohrer, M. Intermittent catheterization in male

neurogenics: No harm to the urethra. Abstract poster 93 presented during Annual Scientific

Meeting of IMSOP, Sydney, Australia 2000. Abstract book p. 112.

16. Farina LA, Palou J. Re: Suprapubic catheterisation and bowel injury. Br J Urol 1993; 72:394.

17. Stéphan F, Sax H, Wachsmuth M, et al. Reduction of urinary tract infection and antibiotic use

after surgery: a controlled, prospective, before-after intervention study. Clin Infect Dis 2006;

42:1544.

Topic 8095 Version 5.0

GRAPHICS

Indications for urinary bladder catheters

Type of catheter

Indications

Indwelling

urethral

Intermittent

urethral

Suprapubic

Condom

Urinary retention

Y

Y

Y

N

Urine output monitoring in critically ill

patient

Y

Y

Y

N

• Patients undergoing prolonged duration

of surgery

Y

N

Y

N

• Patients requiring large volume

infusions or diuretics

Y

N

Y

N

• Patients requiring intraoperative

monitoring of urinary output

Y

N

Y

N

• Patients with urinary incontinence

Y

N

Y

Y

Post-prostate, bladder or gynecologic

surgery

Y

Y

Y

N

Hematuria with clots

Y

N

Y

N

Prolonged immobilization

Y

Y

Y

Y

Urinary incontinence in patients who fail

behavioral and pharmacological therapy and

incontinence pads

Y

N

N

Y

Neurogenic bladder/spinal cord patients

Y

Y

Y

Y

Assist in healing of open sacral or perineal

wounds in incontinent patients

Y

Y

Y

Y

Improve comfort for end of life care

Y

Y

Y

Y

Intra- and post-operative monitoring:

Data from: Gould, CV, Umscheid, CA, Agarwal, RK, et al. Guideline for the prevention of catheterassociated urinary tract infections 2008. Department of Health and Human Services. Centers for

Disease Control and Prevention.

© 2012 UpToDate, Inc. All rights reserved. | Subscription and License Agreement |Release: 20.6 - C20.10

Licensed to: UpToDate Individual Web - FABIO SOUZA |Support Tag: [ecapp1003p.utd.com-177.146.71.2512C53CE97-6.14-178097067]

Placement and management of urinary bladder catheters

Author

Anthony J Schaeffer, MD

Section Editor

Jerome P Richie, MD, FACS

Deputy Editor

Kathryn A Collins, MD, PhD, FACS

Disclosures

All topics are updated as new evidence becomes available and our peer review process is

complete.

Literature review current through: May 2012. | This topic last updated: Out 7, 2010.

INTRODUCTION — Bladder catheters are used for urinary drainage, or as a means to collect

urine for measurement. Many clinical situations are appropriate for the placement of catheters,

but too frequently they are used without proper indication or continued longer than needed.

Daily evaluation of the ongoing need for the catheter is essential to reduce complications.

Alternatives to indwelling urethral catheterization should be considered and include external

sheath (ie, condom) catheters, suprapubic catheters, intermittent catheterization, and in some

cases, supportive management with protective garments.

This topic will discuss the use and management of urinary bladder catheters. Management of

bacteriuria and catheter-associated urinary tract infection is discussed elsewhere. (See"Urinary

tract infection associated with urethral catheters" and "Complications of urinary bladder

catheters and preventive strategies".)

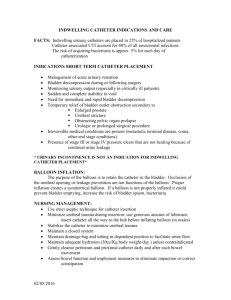

INDICATIONS FOR CATHETERIZATION — The single most important factor for preventing

urinary catheter-related complications is limiting their use to appropriate indications (table

1) [1,2]. Urinary catheters are indicated in the following clinical situations:

Management of acute urinary retention or bladder outlet obstruction. (See "Acute

urinary retention", section on 'Initial management' and "Diagnosis of urinary tract

obstruction and hydronephrosis".)

Urine output measurement in critically ill patients.

During surgery to assess fluid status (ie, prolonged procedures, large volume fluid

infusion).

During and following specific surgeries of the genitourinary tract or adjacent structures

(ie, urologic, gynecologic, colorectal surgery).

Management of hematuria associated with clots. (See "Etiology and evaluation of

hematuria in adults" and "Blunt genitourinary trauma".)

Management of immobilized patients (eg, stroke, pelvic fracture).

Management of patients with neurogenic bladder. (See "Chronic complications of

spinal cord injury".)

Management of open wounds located in the sacral or perineal regions in patients who

are incontinent. (See "Treatment of pressure ulcers".)

Intravesical pharmacologic therapy (eg, bladder cancer). (See "Treatment of nonmuscle-invasive bladder cancer".)

Improved patient comfort for end of life care. (See "Palliative care: Issues specific to

geriatric patients".)

Management of patients with urinary incontinence following failure of conservative,

behavioral, pharmacologic and surgical therapy [3]. (See "Treatment of urinary

incontinence".)

Contraindications — The only absolute contraindication to the placement of a urethral

catheter is the presence of urethral injury which is typically associated with pelvic trauma [4].

The presence of blood at the meatus or gross hematuria associated with trauma is evaluated

first with retrograde urethrogram; urologic consultation and urethroscopy may be necessary.

(See "Blunt genitourinary trauma", section on 'Retrograde urethrogram'.)

Relative contraindications to urethral catheterization include urethral stricture, recent urinary

tract surgery (ie, urethra, bladder), and the presence of an artificial sphincter. For these issues,

a urologist or urogynecologist should be consulted to assist with management.

If an artificial sphincter is present, it should be de-activated and catheterization limited to a

short period of time. Artificial sphincters are discussed elsewhere. (See "Urinary incontinence

in men", section on 'Artificial urinary sphincter' and "Stress urinary incontinence in women:

Persistent/recurrent symptoms after surgical treatment", section on 'Artificial urinary sphincter'.)

Inappropriate use of catheters — Unwarranted urinary catheters are placed in 21 to 50

percent of hospitalized patients [5-7]. The most common inappropriate indication for placing an

indwelling urethral catheter is management of urinary incontinence [5]. While catheter use in

these patients may have a short-term nursing benefit, the increased risk of complications

associated with their use outweighs any benefit [3,8,9]. (See "Treatment of urinary

incontinence".)

It is also inappropriate to use catheters to obtain urine for testing in individuals who are capable

of voiding spontaneously or who can reliably collect urine for monitoring output [1]. Catheters

are also often used to measure residual urinary bladder volume in hospitalized patients;

however, we prefer the use of a portable ultrasound unit (eg, BladderScan™). These devices

correctly estimate residual volume greater than 50 mL in >90 percent of patients [10].

CHOICE OF CATHETER — The choice of catheter depends upon clinical indication and

expected duration of catheterization. Different catheters can be used during the course of care

reflecting the patient's changing needs (table 1). The best alternative to an indwelling urethral

catheter should be considered. Although urethral catheters are frequently used initially,

substituting external catheters, or intermittent catheterization can reduce complications.

External — External catheter systems are the least invasive for urine drainage and are

available as penile sheath catheters (ie, condom catheters) for men or urinary pouches for men

or women. External catheters are not appropriate for accurate urine measurement or

management of urinary obstruction (table 1). (See 'External catheter systems' below.)

Condom catheters are an effective mode of bladder drainage in men who do not have

evidence for urinary retention or urinary obstruction. They are widely used in chronic care

facilities [11,12]. Contraindications to their use include the presence of penile ulceration or

perineal dermatitis. It is important to ensure the patient has adequate manual dexterity if he is

expected to place the device himself [1].

Advantages of condom catheters are minimization of urethral trauma and improved comfort

and mobility compared with indwelling catheters [13]. The decreased incidence of urinary tract

infection associated with condom catheters is dependent upon patient cooperation and

minimization of catheter manipulation.

The main disadvantage of condom catheters is irritation if attached too tightly; penile

ulceration, scarring, and penile tissue loss can result. Dislodgement and urinary spillage can

also be problematic [13]. (See "Complications of urinary bladder catheters and preventive

strategies".)

Urethral — Urethral catheters are inserted through the tip of the urethra (ie, transurethrally)

and are appropriate for all indications related to catheterization (table 1).

Indwelling — Indwelling urethral catheters are most commonly used in the hospital setting for

short-term bladder drainage (ie, <3 weeks). They are also used for management for patients

with chronic urinary retention who are refractory to, or not candidates for, other interventions

(eg, transurethral resection of the prostate).

Intermittent — Intermittent catheterization, which is the removal of the catheter immediately

after bladder decompression with recatheterization on a scheduled basis, is an alternative to

indwelling catheterization. When intermittent catheterization is used, it must be performed at

regular intervals to prevent bladder overdistention [1]. (See 'Clean intermittent

catheterization' below.)

Intermittent urethral catheterization can be used for either short- or long-term management of

urinary retention or neurogenic bladder dysfunction (eg, patients with spinal cord dysfunction,

myelomeningocele, or bladder atonia) [1,14,15]. Despite its advantage of reducing

complications, intermittent catheterization is not commonly used for short-term catheterization

[16-24].

Intermittent catheterization may not be possible for some patients due to upper-extremity

impairment, discomfort, obesity, or urinary obstruction (eg, enlarged prostate, urethral stricture)

and others who may not be willing to perform the procedure [25].

Suprapubic — Suprapubic catheters are the most invasive catheter and require a surgical

procedure for placement, usually by a urologist or urogynecologist. A suprapubic catheter is

placed through the abdominal wall and into the bladder either intraoperatively in association

with another surgical procedure or percutaneously.

Suprapubic catheterization prevents urethral trauma and stricture formation, reduces the

incidence of catheter-associated bacteriuria (at least temporarily), and may be associated with

increased patient satisfaction compared with chronic indwelling urethral catheters. Suprapubic

catheterization allows attempts at normal voiding without the need for recatheterization and

interferes less with sexual activity. Patient comfort and preference usually dictate the choice.

Various types of suprapubic tubes are available including balloon (eg, Foley, Rutner) and

mushroom (eg, Malecot) catheters with a single lumen in sizes ranging from 10 to 18 F. No

benefit has been shown for any particular catheter [25].

CATHETER TECHNOLOGY — Most catheters have dual lumen tubes with one lumen draining

the catheter and the other delivering water to the balloon. The first balloon catheter was

designed in the 1930s by a surgeon, Frederic Foley; the basic catheter retains his name.

For most adults requiring urethral catheterization, a standard Foley catheter (ie, double-lumen

latex) is appropriate. Single or multiple-use straight catheters without a balloon are used for

intermittent catheterization.

Sizing — Catheter size should be individualized to the needs of the patient. In adults, a 14 to

16 French (Fr/3 = diameter in millimeters) catheter is typically chosen for short-term indwelling

catheterization. Larger catheters, 20 to 24 F, are used to provide an adequate bore for the

drainage of hematuria or clots. Sizing charts are available to determine the proper diameter for

children.

Both short (21 cm) and longer (40 to 45 cm) catheter lengths are available. Shorter catheters

may be more appropriate for women.

Two balloon volumes are available, 5 mL and 20 to 30 mL. For most patients, a 5 mL balloon is

adequate. A larger balloon volume may be desirable in some postoperative patients or women

with weak pelvic musculature if urine leakage occurs [26]. (See 'Managing leakage' below.)

External sheath catheters (ie, condom catheters) are available in many sizes and use of a

measurement or sizing guide is recommended. Penile circumferential measurement is taken at

the mid shaft of the non-erect penis as it is gently extended away from the body. Size is

adjusted as needed.

Materials — Catheters are manufactured from latex, silicone, plastic, or Teflon®. Latex

catheters are inexpensive and the most commonly used. However, latex is associated urethral

inflammation which may be due to protein and salt encrustation on the surface of the catheter.

Chronic inflammation from prolonged catheter use can lead to urethral stricture. [27,28]. For

this reason and the potential for latex allergy, silicone catheters may be preferable when more

prolonged catheterization is required [1]. (See "Complications of urinary bladder catheters and

preventive strategies", section on 'Urethral catheters'.)

External catheter systems — Condom catheters are available in latex and silicone.

Removable tips are available for men who also need to perform intermittent catheterization.

Most sheath catheters are pre-rolled and incorporate a self-adhesive vertical strip which

provides penile fixation. Self-adhesive sheaths have fewer complications compared with those

that require separate adhesive strips or other fixating devices. These are often circumferentially

placed and can cause undue tissue compression. (See "Complications of urinary bladder

catheters and preventive strategies", section on 'Condom catheters'.)

Options for males with a small or retracted penis include catheters that adhere directly to the

glans penis, and adhesive urinary pouches. Adhesive urinary pouches are also available for

women.

Specialized catheters — Specialized catheters are available for use as the need arises and

include coudé, triple lumen, antibiotic-coated, and hydrophilic catheters.

Coudé (ie, bent) catheters have a curved tip that facilitates catheter placement in

males, especially those with obstructive uropathy due to benign prostatic hyperplasia.

Triple-lumen catheters are used for bladder irrigation and are available in larger

diameters (20 to 24 F) to aid removal of clot. Irrigation fluid is instilled into the bladder

through the irrigation port and drained through the catheter. Intermittent or continuous

irrigation can be used depending upon the indication for irrigation.

Antimicrobial catheters are coated with antimicrobial agents (eg,

nitrofurazone, minocycline, or rifampin) or silver alloy. While these catheters reduce the

incidence of bacteriuria, they have not been shown to consistently reduce the incidence

of catheter-associated urinary tract infection [27-38]. These catheters are also more

costly [1].

Low friction hydrophilic catheters (eg, LoFric®) do not require lubrication for insertion

and may be useful when intermittent catheterization is needed. In observational

studies, hydrophilic catheters reduce urethral inflammation and are associated with

improved patient satisfaction in some, but not all, studies [39-41]. Catheter-related

bacteriuria, urinary tract infection, or sequelae of urethral problems in patients

managed with intermittent catheterization are not significantly reduced compared with

standard catheters [39]. These catheters are also more expensive.

Catheter drainage systems — Because between 10 to 25 percent of patients who develop

catheter-associated bacteriuria will develop a symptomatic urinary tract infection, catheter

drainage systems have been designed to limit the development of bacteriuria [42]. Based

primarily upon a prospective study of 676 patients, the use of closed catheter urinary drainage

system is the standard of care [43]. In this prospective trial, the incidence of bacteriuria in

patients managed with continuously closed urinary drainage was 23 percent compared with a

reported historic incidence of 95 percent for open urinary drainage. The pathogenesis of

urinary tract infection in the presence of urinary catheters is discussed separately.

(See "Urinary tract infection associated with urethral catheters", section on 'Epidemiology and

pathogenesis'.)

For patients who develop bacteriuria, the drainage bag represents a large reservoir of

pathogens, many of which are resistant to antimicrobials [44-49]. Cross-contamination of

bacteria from one patient to another is possible, and outbreaks of urinary tract infection with

highly resistant organisms have occurred. As such, gloves should be worn whenever the

catheter and drainage system are manipulated. (See 'Hygiene' below.)

Pre-connected systems (catheter is pre-attached to the tubing of a closed drainage bag) may

reduce bacteriuria, but there are insufficient data to support a reduction in the incidence of

catheter-associated urinary tract infection [50]. The application of tape at the catheter-drainage

tubing junction does not reduce the incidence of bacteriuria [25,51]. Randomized trials

evaluating more complex drainage systems, including those that release antiseptic solutions

into the drainage bag, have not demonstrated a reduction in the incidence of urinary tract

infection [1,38,42,52-55].

We prefer to use a sterile, continuously closed drainage system with a needle aspiration port,

and antireflux device to prevent urine backflow. We replace the drainage unit for any disruption

in the urine collection system (ie, catheter disconnect). (See 'Catheter care' below.)

EXTERNAL CATHETER PLACEMENT — The application and maintenance of external

catheters (eg, condom catheter), while simple in theory, can be challenging. Nonsterile gloves

should be used when applying or handling the device. The prior device is removed gently with

careful removal of any adhesive; adhesive remover can also be used. Devices are placed per

manufacturer’s instructions.

For self adhesive penile condom catheters, the penis is cleansed with soap and water and

dried prior to application of the new device. The condom catheter is applied to the tip of the

penis and rolled up the length of the penis, gently pressing the self-adhesive strip into place. It

is important to unroll as completely as possible to minimize any residual roller ring which can

produce tissue compression. (See "Complications of urinary bladder catheters and preventive

strategies", section on 'Condom catheters'.)

TRANSURETHRAL CATHETER PLACEMENT — Both indwelling and intermittent urethral

catheters are placed in a similar fashion. The catheter used for intermittent catheterization is

easier to insert; it is less bulky at the tip because there is no balloon. While indwelling catheter

placement is always performed with sterile technique, intermittent catheterization can be

performed with either sterile or nonsterile, clean technique. (See 'Clean intermittent

catheterization' below.)

A typical urethral catheterization kit includes sterile gloves, drapes, antiseptic solution and

sponges for periurethral cleansing, a single-use lubricant gel packet, urinary catheter, 5 mL

syringe filled with sterile water for balloon inflation, and urine drainage system.

The patient is placed in a supine position. In women, the lower extremities are frog-legged to

maximize exposure of the periurethral region. Adequate lighting is essential. Sterile gloves are

donned and the catheterization kit is inspected to ensure its contents are complete and free of

defects. If an indwelling catheter is chosen, the balloon is inflated briefly to check its integrity.

The end of the catheter, if not pre-attached, can be attached to the drainage system before or

after catheter placement.

Drapes are placed and the periurethral region cleansed. In men, the penis is grasped firmly

with the nondominant hand and tension directed toward the ceiling straightening the urethra. In

women, the nondominant hand is used to spread the labia to facilitate cleansing the

periurethral region and viewing the urethral meatus.

The gloved dominant hand is used to place the catheter into the urethral meatus and steady

gentle pressure used to advance the catheter. When a coude catheter is used, the curved tip of

the catheter should point caudally. When the catheter tip approaches the external sphincter in

men, resistance will be felt. It is often helpful to pause momentarily to let the sphincter relax

before continuing insertion.

The catheter should be inserted to the flared portion of the catheter (ie, hub). The balloon is

inflated with sterile water only after the flow of urine is seen. Saline should not be used to

inflate the balloon because crystal formation may obstruct the balloon channel and prevent

balloon deflation [56]. (See 'Troubleshooting catheter removal' below.)

Once the balloon is inflated, the catheter is withdrawn until slight resistance is felt. The urine

collection system is connected and the drainage tubing anchored to the leg with tape to

prevent traction of the catheter on the urethral meatus [24].

Troubleshooting urethral catheter placement — If no urine is obtained, an assistant can be

asked to apply gentle pressure to the suprapubic region which may initiate urine flow. In

women the insertion site of the catheter is examined; vaginal catheterization may have

occurred. If this is the case, the catheter is removed and a new sterile catheter used.

If the catheter has passed easily to its hub, suprapubic pressure has been applied, and urine is

still not observed, the patient may be dehydrated or may have voided recently. Gentle irrigation

through the end of the catheter using 10 to 20 mL sterile saline can be performed and should

return the saline mixed with urine. If the saline is not returned or any resistance to

catheterization was encountered, underlying pathology may be present and urologic

consultation should be obtained.

If the patient complains of pain during catheter insertion, the catheter should be removed. If

blood appears at the meatus or on the tip of the catheter, a urethral injury may have occurred.

The procedure is abandoned and a urologic consultation is obtained. (See "Complications of

urinary bladder catheters and preventive strategies", section on 'Effects of urethral trauma'.)

Clean intermittent catheterization — Patient populations that benefit from clean intermittent

catheterization (CIC) technique are adults and children with neurogenic bladder, including

patients with spinal cord injury [9,13,57]. Clean (non-sterile) technique for intermittent

catheterization is safe with lower complication rates compared with indwelling urethral or

suprapubic catheterization [14,16-23]. (See "Complications of urinary bladder catheters and

preventive strategies".)

No differences in the incidence of asymptomatic bacteriuria or catheter-associated urinary tract

infection have been found in randomized trials comparing sterile to clean technique for

intermittent catheterization [29,39], or single use compared with multi-use catheters [25].

(See "Urinary tract infection associated with urethral catheters".)

The technique for clean intermittent catheterization is generally the same as indwelling catheter

placement except the option for clean technique, and the removal of the catheter following

bladder drainage. If the catheter is disposable, it is discarded immediately after use. Reusable

catheters are also available and can be used for up to four weeks. Following catheterization,

the reusable catheter is washed with soap, rinsed with water, dried, and stored in a clean, dry

location.

Outpatient, chronic CIC can be challenging for the patient. Instructions to assist performing

intermittent catheterization are as follows [58]:

For men — Once all equipment (ie, catheter, lubricant, drainage receptacle) is

assembled and the hands are washed thoroughly with soap and water, clean the

urethral meatus with soap and water. Lubricate the catheter and gently insert into the

urethra with the penis positioned perpendicular to the body. As resistance is felt at the

level of the prostate, relax and breathe deeply then continue to advance the catheter.

Once the urine starts to flow, continue to advance the catheter another inch. Hold the

catheter in place until the urine flow stops and the bladder is empty. Remove the

catheter slowly to allow complete drainage of the bladder.

For women — Assemble all equipment and wash the hands with soap and water.

Clean intermittent catheterization can be performed in any comfortable position;

however, many women find it easiest to stand with one foot on the toilet. Clean the

vulva with soap and water. With the nondominant hand, spread the labia with the

second and fourth finger, using the middle finger to locate the urethral opening, which

is below the clitoris and above the vagina. Gently insert the catheter into the opening

with the dominant hand. Guide the catheter toward the umbilicus (ie, belly button).

Urine will begin to flow when the catheter has been inserted two to three inches.

Advance the catheter another inch and hold it in place until the urine flow stops and the

bladder is empty. Remove the catheter slowly to allow complete drainage of the

bladder.

SUPRAPUBIC CATHETER PLACEMENT — Suprapubic tube insertion is performed by a

surgeon, usually a urologist or urogynecologist, with either a percutaneous or open surgical

technique. Open suprapubic catheter placement is usually in association with other surgeries

(eg, prostate, bladder trauma repair). A 12 to 14 F catheter is generally selected. If the patient

has a history of prior lower abdominal surgery, percutaneous suprapubic catheters should not

be attempted without simultaneous cystoscopy.

The percutaneous procedure is performed using sterile technique with local anesthesia, and

sedation if needed. Ultrasound is used to verify full bladder distension prior to the procedure.

The catheter can be place via either a direct puncture or Seldinger technique (figure 1).

CATHETER CARE — Ideal catheter care is easy to prescribe but difficult to achieve [59]. A

Danish study using questionnaires to assess knowledge of and adherence to optimal catheter

management protocols in hospitals and nursing homes showed moderate familiarity with

written guidelines but frequent irregularities in practice [60].

Hygiene — Cleansing with soap and water around the catheter (periurethral, suprapubic)

during bathing is adequate for ongoing maintenance. For urethral catheters, we do not use

meatal disinfectants or antibacterial urethral lubricants because they do not prevent infection,

and may lead to development of resistant bacteria at the meatus [61-63].

When the catheter or drainage system is manipulated for any reason, nonsterile gloves should

be used and then immediately discarded to limit transfer of pathogens from patient to patient.

The bag should be emptied regularly, avoiding contact of the drainage spigot with the collecting

container [1,59]. Separate collecting containers should be used for each patient.

Managing leakage — If leakage occurs around an established suprapubic catheter (>6 weeks

after placement) or transurethral catheter, the catheter can be replaced with a new catheter

that is larger by 2 to 4 F.

Leakage can be due to detrusor overactivity/uninhibited bladder contractions, particularly in

some patients with neurologic conditions (eg, multiple sclerosis). In this setting, other

approaches including partially deflating the balloon, or treatment with antimuscarinic

medications may be effective.

If leakage persists or the suprapubic catheter has been more recently placed, a urologist or

urogynecologist should be consulted.

Monitoring for obstruction/preventing backflow — The catheter and collecting tubing

should be free from kinking and fixed to the patient’s leg by a strap or tape to prevent tugging

or inadvertent traumatic removal. The collection system must be positioned below the level of

the bladder at all times. Leg urinary collection bags that are strapped to the thigh are available

for ambulatory use. If the catheter or drainage system is manipulated to relieve an obstruction,

gloves (nonsterile) should be used.

Urine specimen collection — Specimens should not be obtained from the drainage bag when

collecting urine for gram stain or culture. If specimens are required for other analysis (eg,

creatinine clearance) they can be obtained aseptically from the drainage bag [1,64,65].

Procedures for obtaining urine samples for microbiologic analysis are discussed separately.

(See "Urinary tract infection associated with urethral catheters", section on 'Diagnosis'.)

Changing the catheter — Indwelling catheters as a rule should not be replaced routinely; they

should not be changed if flow appears adequate [66]. Although there is a brief reduction in the

density of bacteria found in the urine following catheter replacement, this is a short-lived

phenomenon of uncertain benefit [67]. However, catheters with mechanical problems (poor

drainage, encrusted) need to be replaced.

Suprapubic catheters are generally managed by the operating surgeon and are not changed

until a tract between the bladder and abdominal wall is established, which usually requires four

to six weeks. If the catheter is accidentally pulled out within six weeks of its placement, the

operating surgeon should be notified.

Bladder irrigation — Bladder irrigation is reserved for selected patients (eg, postoperative,

pharmacologic therapy) or for the management of hematuria. However, if a catheter is not

draining properly, it can be irrigated once with sterile saline [1]. If this is not effective, the

catheter should be replaced. If there is a suspicion that the latex catheter material contributed

to the obstruction, the catheter should be changed to a silicone catheter to reduce future

encrustation.

Antimicrobial irrigation of the bladder does not appear to prevent or delay urinary tract

infection; rather, this practice may lead to infection with more resistant organisms [68-70]. One

randomized trial of 200 catheterized patients found no significant difference in the incidence of

urinary tract infection for patients treated with a neomycin-polymyxin bladder irrigant compared

with no irrigation [68]. Patients who received bladder irrigation were found to have more

resistant organisms.

Catheter removal — The simplest strategy for preventing catheter-related urinary tract

infection is catheter removal when the indication for insertion is no longer met. Removing an

indwelling urethral catheter is usually a matter of aspirating the balloon port with an empty

syringe which deflates the balloon; the catheter should then slip out. Suprapubic catheters are

typically removed by the operating surgeon once the indication for catheter placement has

resolved.

Following surgery, catheters should be removed as soon as possible (ideally in the recovery

room) to reduce the incidence of urinary tract infection [71,72]. A meta-analysis of 7

randomized trials found fewer urinary tract infections when urinary catheters were removed

within one day postoperatively compared with three days (relative risk 0.50, 95% CI, 0.29-0.87)

[72].

On occasion, clinicians may be unaware that their patient has a urinary catheter, especially if it

had been replaced after initial removal [73]. Reminders from nursing staff and implementation

of automatic stop orders reduce the duration of catheterization and incidence of catheterassociated urinary tract infection [74,75]. A systematic review and meta-analysis of 14 studies

that evaluated reminder systems found a 52 percent reduction in the rate (episodes per 1000

catheter-days) of catheter-associated urinary tract infection with the use of a reminder or stop

order (rate ratio [RR] 0.48, 95% CI 0.28-0.69). The duration of catheterization was decreased

by 37 percent [75].

Troubleshooting catheter removal — The balloon of a urinary catheter may fail to deflate

properly due to a faulty valve mechanism or obstructed balloon channel. Obstruction is

uncommon and is typically due to the formation of crystals when saline rather than water is

used to inflate the balloon, and the catheter has been in place for a prolonged period of time.

The first line of action if the fluid within the balloon cannot be aspirated is to cut the valve (ie,

balloon port) from the catheter at its junction. This should result in immediate flow of water from

the balloon. To minimize the potential for urethral trauma, allow some time for the balloon to

drain before withdrawing the catheter. Rupturing the balloon by overinflation should not be

attempted since balloon fragmentation will result about 80 percent of the time requiring

cystoscopy for retrieval [76]. If cutting the valve fails to deflate the balloon, a urologist or

urogynecologist should be consulted. He or she will typically first try to maneuver a ureteric

stylet through the inflation channel to dislodge the obstruction. If this fails, the patient will need

to be sedated and the balloon punctured sharply with a spinal needle, using a transabdominal,

transurethral, or transvaginal approach.

Prophylactic antibiotics — Systemic antimicrobial agents should not be administered to

patients who do not have a proven urinary tract infection in either a short- or long-term

catheterization setting [67,77,78]. Antimicrobial therapy promotes the development of resistant

bacterial strains. (See "Urinary tract infection associated with urethral catheters", section on

'Asymptomatic bacteriuria' and "Urinary tract infection associated with urethral catheters",

section on 'Urinary tract infection'.)

COMPLICATIONS — The complications of urinary catheter placement are discussed in detail

elsewhere. (See "Complications of urinary bladder catheters and preventive strategies".)

SUMMARY AND RECOMMENDATIONS

Catheters available for urinary drainage include external (eg, condom), urethral

(indwelling, intermittent), and suprapubic catheters. (See 'Choice of catheter' above.)

There are many indications for using bladder catheters (table 1). Limiting use to

appropriate indications is important in minimizing catheter-related complications.

Catheters are not indicated for determining the residual volume of urine, or in the

management of most patients with urinary incontinence (see 'Inappropriate use of

catheters' above).

Urinary catheters are used selectively for operative patients based upon the nature (ie,

pelvic surgery) and duration of the procedure, or need for perioperative fluid

monitoring. Catheters should be removed as soon as possible, preferably in the

recovery area, if feasible. (See 'Indications for catheterization' above and 'Catheter

removal' above.)

For male patients who do not have evidence of urinary retention or bladder outlet

obstruction, we suggest external catheters over urethral catheters whenever possible

(Grade 2C). (See 'Choice of catheter' above.)

For patients with bladder emptying dysfunction, we suggest intermittent catheterization

over chronic indwelling catheters (Grade 2C). Clean technique is an acceptable and

practical alternative to sterile technique. (See 'Choice of catheter' above and 'Clean

intermittent catheterization' above.)

Following aseptic placement of indwelling catheters, we recommend a closed drainage

system (Grade 1C). Breaks in the integrity of the closed system should prompt

replacement of the drainage system. (See 'Catheter drainage systems' above.)

Routine maintenance of urinary catheters includes proper hygiene of the pericatheter

region, maintenance of unobstructed urine flow, frequent and proper emptying of the

closed catheter drainage system, and proper specimen collection. (See 'Catheter

care' above.)

Indwelling urethral catheters and drainage systems are changed only for a specific

clinical indication such as infection, obstruction, or compromise of closed system

integrity. (See 'Catheter care' above.)

For patients who do not have gross hematuria associated with clots, we suggest not

irrigating urinary catheters (Grade 2C). (See 'Catheter care' above.)

Use of UpToDate is subject to the Subscription and License Agreement.

REFERENCES

1. Gould, C, Umscheid, C, Agarwal, R, et al. Guideline for the Prevention of Catheter-Associated

Urinary Tract Infections 2008, HaH Services (Ed), Department of Health and Human Sevices

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta 2008. pp.1-47.

2. Nicolle LE. Catheter-related urinary tract infection. Drugs Aging 2005; 22:627.

3. Abrams P, Andersson KE, Birder L, et al. Fourth International Consultation on Incontinence

Recommendations of the International Scientific Committee: Evaluation and treatment of

urinary incontinence, pelvic organ prolapse, and fecal incontinence. Neurourol Urodyn 2010;

29:213.

4. Cravens DD, Zweig S. Urinary catheter management. Am Fam Physician 2000; 61:369.

5. Jain P, Parada JP, David A, Smith LG. Overuse of the indwelling urinary tract catheter in

hospitalized medical patients. Arch Intern Med 1995; 155:1425.

6. Gardam MA, Amihod B, Orenstein P, et al. Overutilization of indwelling urinary catheters and

the development of nosocomial urinary tract infections. Clin Perform Qual Health Care 1998;

6:99.

7. Holroyd-Leduc, JM, Sands, LP, Counsell, SR, et al. Risk factors for indwelling urinary

catheterization among older hospitalized patients without a specific medical indication for

catheterization. J Patient Saf 2005; 1:201.

8. Givens CD, Wenzel RP. Catheter-associated urinary tract infections in surgical patients: a

controlled study on the excess morbidity and costs. J Urol 1980; 124:646.

9. Tambyah PA, Knasinski V, Maki DG. The direct costs of nosocomial catheter-associated

urinary tract infection in the era of managed care. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 2002; 23:27.

10. Fuse H, Yokoyama T, Muraishi Y, Katayama T. Measurement of residual urine volume using a

portable ultrasound instrument. Int Urol Nephrol 1996; 28:633.

11. Warren JW, Steinberg L, Hebel JR, Tenney JH. The prevalence of urethral catheterization in

Maryland nursing homes. Arch Intern Med 1989; 149:1535.

12. Saint S, Kaufman SR, Rogers MA, et al. Condom versus indwelling urinary catheters: a

randomized trial. J Am Geriatr Soc 2006; 54:1055.

13. Saint S, Lipsky BA, Baker PD, et al. Urinary catheters: what type do men and their nurses

prefer? J Am Geriatr Soc 1999; 47:1453.

14. Terpenning MS, Allada R, Kauffman CA. Intermittent urethral catheterization in the elderly. J

Am Geriatr Soc 1989; 37:411.

15. Moore KN, Burt J, Voaklander DC. Intermittent catheterization in the rehabilitation setting: a

comparison of clean and sterile technique. Clin Rehabil 2006; 20:461.

16. Lapides J, Diokno AC, Silber SJ, Lowe BS. Clean, intermittent self-catheterization in the

treatment of urinary tract disease. J Urol 1972; 107:458.

17. Consortium for Spinal Cord Medicine. Bladder management for adults with spinal cord injury: a

clinical practice guideline for health-care providers. J Spinal Cord Med 2006; 29:527.

18. Wyndaele JJ. Complications of intermittent catheterization: their prevention and treatment.

Spinal Cord 2002; 40:536.

19. Duffy LM, Cleary J, Ahern S, et al. Clean intermittent catheterization: safe, cost-effective

bladder management for male residents of VA nursing homes. J Am Geriatr Soc 1995; 43:865.

20. Niël-Weise BS, van den Broek PJ. Urinary catheter policies for short-term bladder drainage in

adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2005; :CD004203.

21. Carapeti EA, Andrews SM, Bentley PG. Randomised study of sterile versus non-sterile urethral

catheterisation. Ann R Coll Surg Engl 1996; 78:59.

22. Anderson RU. Non-sterile intermittent catheterization with antibiotic prophylaxis in the acute

spinal cord injured male patient. J Urol 1980; 124:392.

23. Shekelle PG, Morton SC, Clark KA, et al. Systematic review of risk factors for urinary tract

infection in adults with spinal cord dysfunction. J Spinal Cord Med 1999; 22:258.

24. Saint S. Clinical and economic consequences of nosocomial catheter-related bacteriuria. Am J

Infect Control 2000; 28:68.

25. Hooton, T, Bradley, S, Cardenas, D, et al. International Clinical Practice Guidelines for the

Diagnosis, Prevention, and Treatment of Catheter-Associated Urinary Tract Infection in Adults

2009. pp.1-81.

26. Belfield PW. Urinary catheters. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed) 1988; 296:836.

27. Srinivasan A, Karchmer T, Richards A, et al. A prospective trial of a novel, silicone-based,

silver-coated foley catheter for the prevention of nosocomial urinary tract infections. Infect

Control Hosp Epidemiol 2006; 27:38.

28. Brosnahan J, Jull A, Tracy C. Types of urethral catheters for management of short-term voiding

problems in hospitalised adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2004; :CD004013.

29. Newton T, Still JM, Law E. A comparison of the effect of early insertion of standard latex and

silver-impregnated latex foley catheters on urinary tract infections in burn patients. Infect

Control Hosp Epidemiol 2002; 23:217.

30. Johnson JR, Roberts PL, Olsen RJ, et al. Prevention of catheter-associated urinary tract

infection with a silver oxide-coated urinary catheter: clinical and microbiologic correlates. J

Infect Dis 1990; 162:1145.

31. Riley DK, Classen DC, Stevens LE, Burke JP. A large randomized clinical trial of a silverimpregnated urinary catheter: lack of efficacy and staphylococcal superinfection. Am J Med

1995; 98:349.

32. Saint S, Elmore JG, Sullivan SD, et al. The efficacy of silver alloy-coated urinary catheters in

preventing urinary tract infection: a meta-analysis. Am J Med 1998; 105:236.

33. Johnson JR, Kuskowski MA, Wilt TJ. Systematic review: antimicrobial urinary catheters to

prevent catheter-associated urinary tract infection in hospitalized patients. Ann Intern Med

2006; 144:116.

34. Stensballe J, Tvede M, Looms D, et al. Infection risk with nitrofurazone-impregnated urinary

catheters in trauma patients: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med 2007; 147:285.

35. Karchmer TB, Giannetta ET, Muto CA, et al. A randomized crossover study of silver-coated

urinary catheters in hospitalized patients. Arch Intern Med 2000; 160:3294.

36. Saint S, Veenstra DL, Sullivan SD, et al. The potential clinical and economic benefits of silver

alloy urinary catheters in preventing urinary tract infection. Arch Intern Med 2000; 160:2670.

37. Rupp ME, Fitzgerald T, Marion N, et al. Effect of silver-coated urinary catheters: efficacy, costeffectiveness, and antimicrobial resistance. Am J Infect Control 2004; 32:445.

38. Reiche T, Lisby G, Jørgensen S, et al. A prospective, controlled, randomized study of the effect

of a slow-release silver device on the frequency of urinary tract infection in newly catheterized

patients. BJU Int 2000; 85:54.

39. Pachler J, Frimodt-Møller C. A comparison of prelubricated hydrophilic and non-hydrophilic

polyvinyl chloride catheters for urethral catheterization. BJU Int 1999; 83:767.

40. Vaidyanathan S, Soni BM, Dundas S, Krishnan KR. Urethral cytology in spinal cord injury

patients performing intermittent catheterisation. Paraplegia 1994; 32:493.

41. Diokno AC, Mitchell BA, Nash AJ, Kimbrough JA. Patient satisfaction and the LoFric catheter

for clean intermittent catheterization. J Urol 1995; 153:349.

42. Lanara V, Plati C, Paniara O, et al. The prevalence of urinary tract infection in patients related

to type of drainage bag. Scand J Caring Sci 1988; 2:163.

43. Kunin CM, McCormack RC. Prevention of catheter-induced urinary-tract infections by sterile

closed drainage. N Engl J Med 1966; 274:1155.

44. Schaberg DR, Haley RW, Highsmith AK, et al. Nosocomial bacteriuria: a prospective study of

case clustering and antimicrobial resistance. Ann Intern Med 1980; 93:420.

45. Schaberg DR, Alford RH, Anderson R, et al. An outbreak of nosocomial infection due to

multiply resistant Serratia marcescens: evidence of interhospital spread. J Infect Dis 1976;

134:181.

46. Jarlier V, Fosse T, Philippon A. Antibiotic susceptibility in aerobic gram-negative bacilli isolated

in intensive care units in 39 French teaching hospitals (ICU study). Intensive Care Med 1996;

22:1057.

47. Bjork DT, Pelletier LL, Tight RR. Urinary tract infections with antibiotic resistant organisms in

catheterized nursing home patients. Infect Control 1984; 5:173.

48. Krieger JN, Kaiser DL, Wenzel RP. Nosocomial urinary tract infections cause wound infections

postoperatively in surgical patients. Surg Gynecol Obstet 1983; 156:313.

49. Wagenlehner FM, Krcmery S, Held C, et al. Epidemiological analysis of the spread of

pathogens from a urological ward using genotypic, phenotypic and clinical parameters. Int J

Antimicrob Agents 2002; 19:583.

50. DeGroot-Kosolcharoen J, Guse R, Jones JM. Evaluation of a urinary catheter with a

preconnected closed drainage bag. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 1988; 9:72.

51. Huth TS, Burke JP, Larsen RA, et al. Clinical trial of junction seals for the prevention of urinary

catheter-associated bacteriuria. Arch Intern Med 1992; 152:807.

52. Wille JC, Blussé van Oud Alblas A, Thewessen EA. Nosocomial catheter-associated

bacteriuria: a clinical trial comparing two closed urinary drainage systems. J Hosp Infect 1993;

25:191.

53. Danachaivijitr. S. Should the open urinary drainage system be continued. J Med Assoc Thai

1988; 71:S14.

54. Leone M, Garnier F, Dubuc M, et al. Prevention of nosocomial urinary tract infection in ICU

patients: comparison of effectiveness of two urinary drainage systems. Chest 2001; 120:220.

55. Leone M, Garnier F, Antonini F, et al. Comparison of effectiveness of two urinary drainage

systems in intensive care unit: a prospective, randomized clinical trial. Intensive Care Med

2003; 29:410.

56. Daneshmand S, Youssefzadeh D, Skinner EC. Review of techniques to remove a Foley

catheter when the balloon does not deflate. Urology 2002; 59:127.

57. Erickson RP, Merritt JL, Opitz JL, Ilstrup DM. Bacteriuria during follow-up in patients with spinal

cord injury: I. Rates of bacteriuria in various bladder-emptying methods. Arch Phys Med

Rehabil 1982; 63:409.

58. Wyndaele JJ. Intermittent catheterization: which is the optimal technique? Spinal Cord 2002;

40:432.

59. Wong, ES, Hooton, TM. Guidelines for prevention of catheter-associated urinary tract

infections. Infect Control 1981; 2:126.

60. Zimakoff JD, Pontoppidan B, Larsen SO, et al. The management of urinary catheters:

compliance of practice in Danish hospitals, nursing homes and home care to national

guidelines. Scand J Urol Nephrol 1995; 29:299.

61. Burke JP, Garibaldi RA, Britt MR, et al. Prevention of catheter-associated urinary tract

infections. Efficacy of daily meatal care regimens. Am J Med 1981; 70:655.

62. Huth TS, Burke JP, Larsen RA, et al. Randomized trial of meatal care with silver sulfadiazine

cream for the prevention of catheter-associated bacteriuria. J Infect Dis 1992; 165:14.

63. Classen DC, Larsen RA, Burke JP, et al. Daily meatal care for prevention of catheterassociated bacteriuria: results using frequent applications of polyantibiotic cream. Infect

Control Hosp Epidemiol 1991; 12:157.

64. Bergqvist D, Brönnestam R, Hedelin H, Ståhl A. The relevance of urinary sampling methods in

patients with indwelling Foley catheters. Br J Urol 1980; 52:92.

65. Grahn D, Norman DC, White ML, et al. Validity of urinary catheter specimen for diagnosis of

urinary tract infection in the elderly. Arch Intern Med 1985; 145:1858.

66. Kunin CM, Chin QF, Chambers S. Indwelling urinary catheters in the elderly. Relation of

"catheter life" to formation of encrustations in patients with and without blocked catheters. Am J

Med 1987; 82:405.

67. Tenney JH, Warren JW. Bacteriuria in women with long-term catheters: paired comparison of

indwelling and replacement catheters. J Infect Dis 1988; 157:199.

68. Warren JW, Platt R, Thomas RJ, et al. Antibiotic irrigation and catheter-associated urinary-tract

infections. N Engl J Med 1978; 299:570.

69. Schneeberger PM, Vreede RW, Bogdanowicz JF, van Dijk WC. A randomized study on the

effect of bladder irrigation with povidone-iodine before removal of an indwelling catheter. J

Hosp Infect 1992; 21:223.

70. Sweet DE, Goodpasture HC, Holl K, et al. Evaluation of H2O2 prophylaxis of bacteriuria in

patients with long-term indwelling Foley catheters: a randomized controlled study. Infect

Control 1985; 6:263.

71. Wald HL, Ma A, Bratzler DW, Kramer AM. Indwelling urinary catheter use in the postoperative

period: analysis of the national surgical infection prevention project data. Arch Surg 2008;

143:551.

72. Phipps S, Lim YN, McClinton S, et al. Short term urinary catheter policies following urogenital

surgery in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2006; :CD004374.

73. Saint S, Wiese J, Amory JK, et al. Are physicians aware of which of their patients have

indwelling urinary catheters? Am J Med 2000; 109:476.

74. Huang WC, Wann SR, Lin SL, et al. Catheter-associated urinary tract infections in intensive

care units can be reduced by prompting physicians to remove unnecessary catheters. Infect

Control Hosp Epidemiol 2004; 25:974.

75. Meddings J, Rogers MA, Macy M, Saint S. Systematic review and meta-analysis: reminder

systems to reduce catheter-associated urinary tract infections and urinary catheter use in

hospitalized patients. Clin Infect Dis 2010; 51:550.

76. Gülmez I, Ekmekcioglu O, Karacagil M. A comparison of various methods to burst Foley

catheter balloons and the risk of free-fragment formation. Br J Urol 1996; 77:716.

77. Niël-Weise BS, van den Broek PJ. Antibiotic policies for short-term catheter bladder drainage

in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2005; :CD005428.

78. Sandock DS, Gothe BG, Bodner DR. Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole prophylaxis against

urinary tract infection in the chronic spinal cord injury patient. Paraplegia 1995; 33:156.

Topic 8090 Version 6.0

GRAPHICS

Indications for urinary bladder catheters

Type of catheter

Indications

Indwelling

urethral

Intermittent

urethral

Suprapubic

Condom

Urinary retention

Y

Y

Y

N

Urine output monitoring in critically ill

patient

Y

Y

Y

N

• Patients undergoing prolonged duration

of surgery

Y

N

Y

N

• Patients requiring large volume

infusions or diuretics

Y

N

Y

N

• Patients requiring intraoperative

monitoring of urinary output

Y

N

Y

N

• Patients with urinary incontinence

Y

N

Y

Y

Post-prostate, bladder or gynecologic

surgery

Y

Y

Y

N

Hematuria with clots

Y

N

Y

N

Prolonged immobilization

Y

Y

Y

Y

Urinary incontinence in patients who fail

behavioral and pharmacological therapy and

incontinence pads

Y

N

N

Y

Neurogenic bladder/spinal cord patients

Y

Y

Y

Y

Assist in healing of open sacral or perineal

wounds in incontinent patients

Y

Y

Y

Y

Improve comfort for end of life care

Y

Y

Y

Y

Intra- and post-operative monitoring:

Data from: Gould, CV, Umscheid, CA, Agarwal, RK, et al. Guideline for the prevention of catheterassociated urinary tract infections 2008. Department of Health and Human Services. Centers for

Disease Control and Prevention.

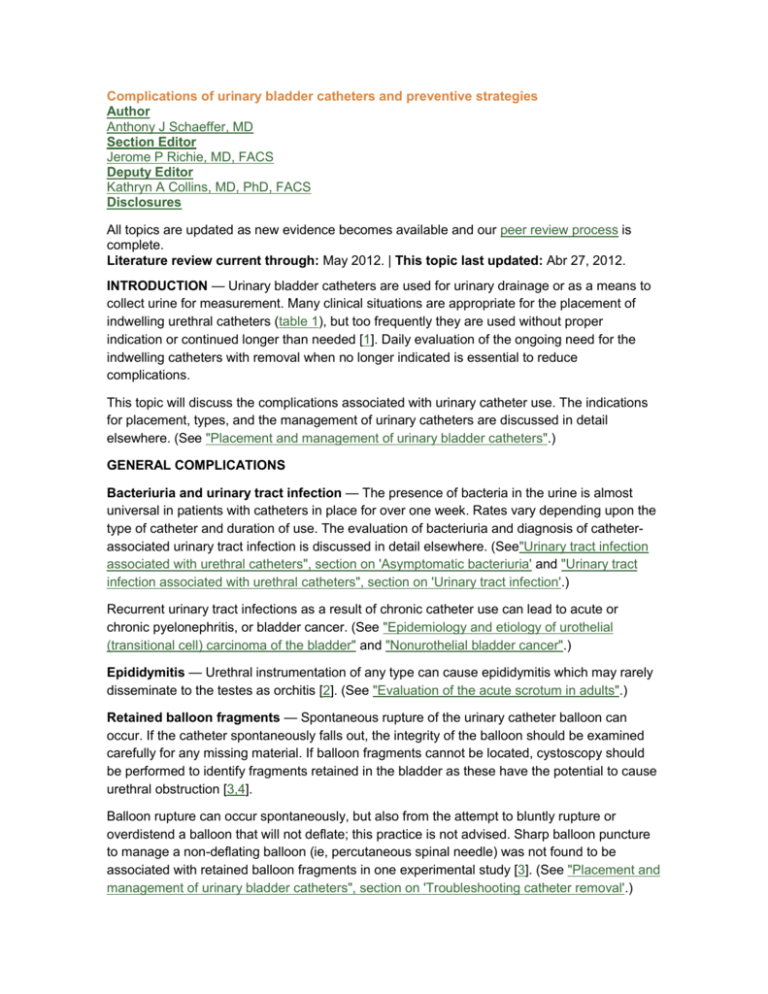

Percutaneous suprapubic catheter placement

Percutaneous suprapubic catheters are placed using sterile technique with local

anesthesia, and sedation if needed. Ultrasound is used to verify full bladder distension

prior to the procedure. The lower abdominal skin is prepared and lidocaine is injected

in the midline, 2 centimeters above the symphysis pubis. The catheter is placed

through a small skin incision into the bladder either with a direct puncture or Seldinger

technique. For the direct puncture technique, a mushroom catheter is straightened

with a stylet and advanced into the bladder. Once the catheter is confirmed within the

bladder, the stylet is removed. For the Seldinger technique, a needle is inserted until

urine is aspirated. A guidewire is placed through the needle into the bladder and the

needle is removed. A dilator is advanced over the wire enlarging the tract. The dilator

is then replaced with a sheath, the guidewire removed, and the catheter placed

through the sheath which is then peeled away. The catheter balloon is inflated and the

catheter gently withdrawn until slight tension is felt. The catheter is then connected to

the catheter drainage system and secured to the patient.

© 2012 UpToDate, Inc. All rights reserved. | Subscription and License Agreement |Release: 20.6 - C20.10

Licensed to: UpToDate Individual Web - FABIO SOUZA |Support Tag: [ecapp1003p.utd.com-177.146.71.2512C53CE97-6.14-178097067]