D10

advertisement

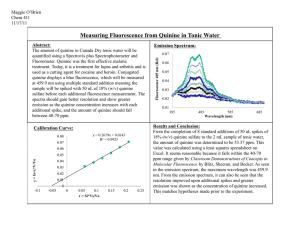

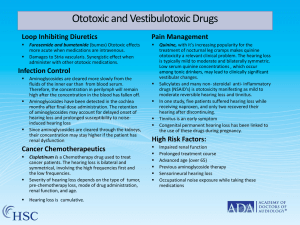

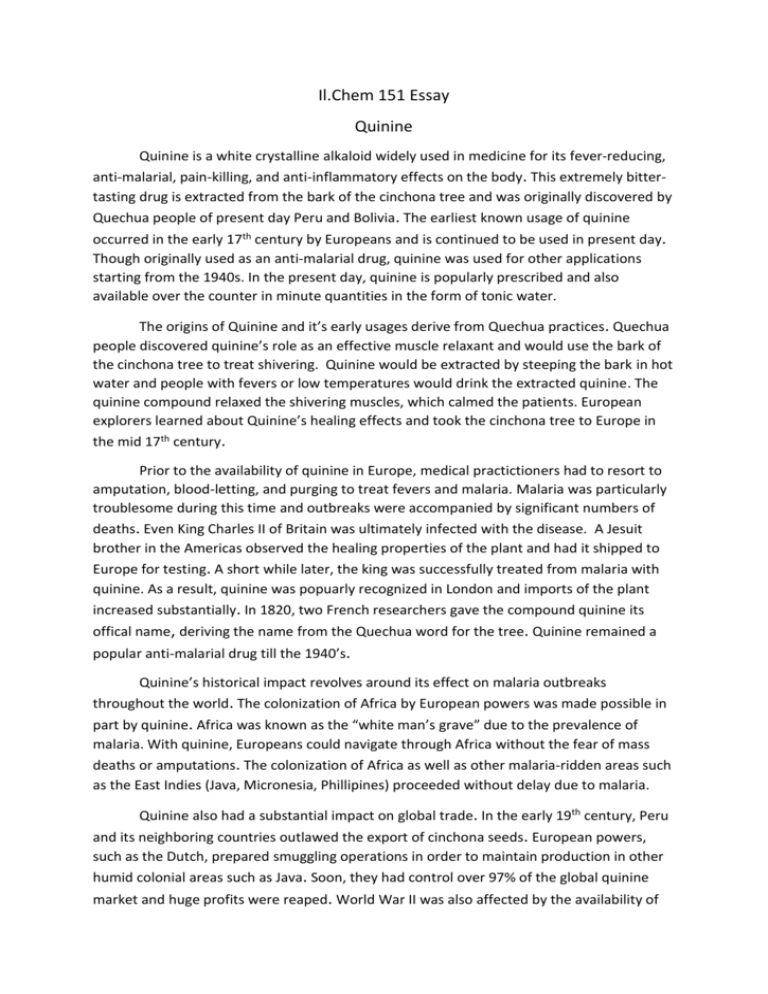

Il.Chem 151 Essay Quinine Quinine is a white crystalline alkaloid widely used in medicine for its fever-reducing, anti-malarial, pain-killing, and anti-inflammatory effects on the body. This extremely bittertasting drug is extracted from the bark of the cinchona tree and was originally discovered by Quechua people of present day Peru and Bolivia. The earliest known usage of quinine occurred in the early 17th century by Europeans and is continued to be used in present day. Though originally used as an anti-malarial drug, quinine was used for other applications starting from the 1940s. In the present day, quinine is popularly prescribed and also available over the counter in minute quantities in the form of tonic water. The origins of Quinine and it’s early usages derive from Quechua practices. Quechua people discovered quinine’s role as an effective muscle relaxant and would use the bark of the cinchona tree to treat shivering. Quinine would be extracted by steeping the bark in hot water and people with fevers or low temperatures would drink the extracted quinine. The quinine compound relaxed the shivering muscles, which calmed the patients. European explorers learned about Quinine’s healing effects and took the cinchona tree to Europe in the mid 17th century. Prior to the availability of quinine in Europe, medical practictioners had to resort to amputation, blood-letting, and purging to treat fevers and malaria. Malaria was particularly troublesome during this time and outbreaks were accompanied by significant numbers of deaths. Even King Charles II of Britain was ultimately infected with the disease. A Jesuit brother in the Americas observed the healing properties of the plant and had it shipped to Europe for testing. A short while later, the king was successfully treated from malaria with quinine. As a result, quinine was popuarly recognized in London and imports of the plant increased substantially. In 1820, two French researchers gave the compound quinine its offical name, deriving the name from the Quechua word for the tree. Quinine remained a popular anti-malarial drug till the 1940’s. Quinine’s historical impact revolves around its effect on malaria outbreaks throughout the world. The colonization of Africa by European powers was made possible in part by quinine. Africa was known as the “white man’s grave” due to the prevalence of malaria. With quinine, Europeans could navigate through Africa without the fear of mass deaths or amputations. The colonization of Africa as well as other malaria-ridden areas such as the East Indies (Java, Micronesia, Phillipines) proceeded without delay due to malaria. Quinine also had a substantial impact on global trade. In the early 19th century, Peru and its neighboring countries outlawed the export of cinchona seeds. European powers, such as the Dutch, prepared smuggling operations in order to maintain production in other humid colonial areas such as Java. Soon, they had control over 97% of the global quinine market and huge profits were reaped. World War II was also affected by the availability of the medicine as well as synthetic variants. When the Germans conquered the Dutch and the Japanese took the Phillipines and Indonesia, the Allied powers were cut off from their quinine supply. The U.S had reserves of quinine seeds and began planting, but due to the lack of supply for the demand, tens of thousands of troops fell to malaria. It was during this time that American researchers attempted to produce quinine synthetically to distribute to American soldiers in the Pacific and Africa. By 1944, two American chemists developed a formal chemical synthesis for quinine. However, harvesting quinine from natural sources was still far more efficient. Since the advent of synthetically prepared quinine, several more efficient quinine total syntheses have been found. However, they still cannot compete with the natural derivation process in terms of efficiency and cost. Drugs of similar nature have also been made which have somewhat replaced quinine’s use in medicine. In 2006, the World Health Organization rescinded its recommendation for quinine being used in treating malaria as a first option. It should only be used in situations were arteminisins are not available. This was the first time in almost 400 years that quinine was no longer considered the best treatment for malaria. However, malaria strains had evolved so synthetic quinine drugs were no longer effective. The World Health Organization experimented with natural quinine and found that the evolved strains of malaria could be treated by medicine derived from natural quinine. The reason for WHO’s decision to not recommend quinine usaage is due to its considerable negative effects. Quinine can cause cinchonism, which is essentially a quinine overdose. Symptoms include flushed skin, tinnitus, pain, impaired hearing, etc, but there are heavier consquences for larger overdoses. Skin rashes, deafness, and anaphylactic shock can lead to blackwater fever. In addition, pulmonary edema’s, constipation, paralysis in case of overdose, and renal failure are also possible side-effects. In the past, quinine was also used to treat leg cramps, but has since been banned by the FDA in 1994 due to adverse health effects. The over the counter availability of quinine has been dropping in first world countries and now usually requires a prescription. However, the risks associated with quinine use are deemed acceptable when attempting to treate malaria as malaria is a lifethreatening disease. Despite the adverse medical effects associated with the therapeutic application, there are some nonmedical regulated uses of quinine. Tonic water dates back to the Quechua people, who would mix quinine and water in order to remove the bitter taste of the drug. The British mixed tonic water and gin back in the times of British India, originating the ‘gin and tonic’ cocktail. Several other alcoholic beverages, such as wine, list quinine as one of their ingredients. The amount of quinine in these commercial drinks are at appropriate levels in order to avoid the harmful side effects. Quinine has a molar mass of 324.4 g and a melting point of 177°C. It is a commonly used as a fluorescence standard in photochemistry due to its defined and constant quantum yield. UV absorption peaks are around 350 nm and fluorescent peaks are around 460 nm. Quantum yield refers to how efficiently absorbed light creates an optical effect. Fluorescence is observed when a substance absorbs photons at the UV range and emits excited photons in the visible spectrum. Quinine creates a blue-green fluorescent effect when subjected to ultraviolet light, as shown in Figure 1. Quinine’s value in the past was immeasurable. A remedy against endemic malaria outbreaks provided a great deal of relief to European citizens who no longer needed to fear the idea of amputation or death if infected. It allowed for further colonization by the European powers in more tropical locations. As the years passed, it became a major commodity in the global trade market. Quinine’s usage entered a down period after the advent of synthetic alternatives in the 1940’s. However, quinine maintained its relevance in today’s world as an anti-malarial drug because of its effectiveness against evolved malarial strains. Quinine has saved many lives over the course of approximately 400 years of use and continues to be a useful compound for scientific study today. Figure 1. Tonic water exposed to UV light.