Do the Write Thing: Teaching with Writing

advertisement

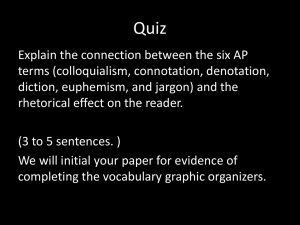

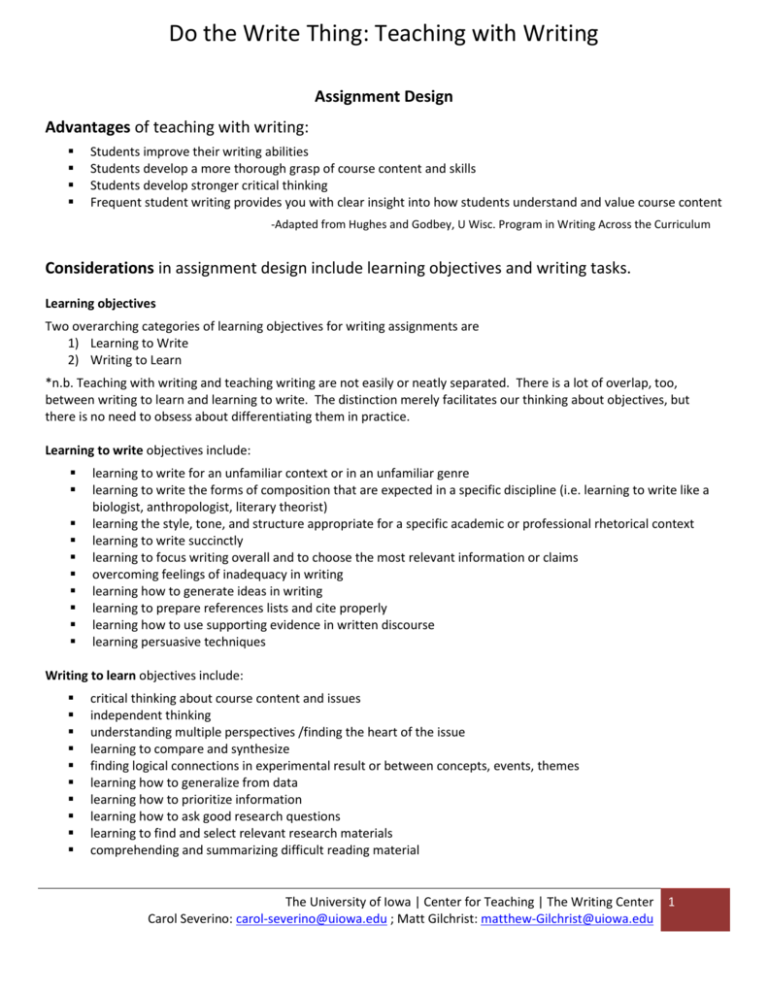

Do the Write Thing: Teaching with Writing Assignment Design Advantages of teaching with writing: Students improve their writing abilities Students develop a more thorough grasp of course content and skills Students develop stronger critical thinking Frequent student writing provides you with clear insight into how students understand and value course content -Adapted from Hughes and Godbey, U Wisc. Program in Writing Across the Curriculum Considerations in assignment design include learning objectives and writing tasks. Learning objectives Two overarching categories of learning objectives for writing assignments are 1) Learning to Write 2) Writing to Learn *n.b. Teaching with writing and teaching writing are not easily or neatly separated. There is a lot of overlap, too, between writing to learn and learning to write. The distinction merely facilitates our thinking about objectives, but there is no need to obsess about differentiating them in practice. Learning to write objectives include: learning to write for an unfamiliar context or in an unfamiliar genre learning to write the forms of composition that are expected in a specific discipline (i.e. learning to write like a biologist, anthropologist, literary theorist) learning the style, tone, and structure appropriate for a specific academic or professional rhetorical context learning to write succinctly learning to focus writing overall and to choose the most relevant information or claims overcoming feelings of inadequacy in writing learning how to generate ideas in writing learning to prepare references lists and cite properly learning how to use supporting evidence in written discourse learning persuasive techniques Writing to learn objectives include: critical thinking about course content and issues independent thinking understanding multiple perspectives /finding the heart of the issue learning to compare and synthesize finding logical connections in experimental result or between concepts, events, themes learning how to generalize from data learning how to prioritize information learning how to ask good research questions learning to find and select relevant research materials comprehending and summarizing difficult reading material The University of Iowa | Center for Teaching | The Writing Center Carol Severino: carol-severino@uiowa.edu ; Matt Gilchrist: matthew-Gilchrist@uiowa.edu 1 Do the Write Thing: Teaching with Writing Assignment Design (cont.) Writing tasks Writing tasks define what it is that students are doing when they write. Tasks can be thought of as corresponding to writing to learn and learning to write objectives, and academic tasks could be grouped into six task genres: Writing to Learn Learning to Write Reading Responses Professional Writing Analysis of Text Reports of Empirical Research Arguments from or about Sources Application of Course Concepts to the Real World Writing to learn: Reading responses: Freewriting, discussion points, journaling, microtheme, summary Analysis of text: Book review, literature review, rhetorical analysis, annotated bibliography Arguments from or about sources: Position paper, research paper, proposals and prospectuses Learning to write: Professional writing: Personal statements, résumés, letters of application, disciplinary forms like white papers Reports of empirical research: Final course papers based on research results, conference proposals and presentations, articles for publication, thesis and dissertation prospectuses, and the theses and dissertations themselves Application of course concepts to the real world: Act as if paper, evaluation of the current state of the field Thinking critically about the learning objectives you want to accomplish and the writing tasks that will best accomplish those objectives will help you zero in on the most effective approach to composing an assignment. *Prezi URL: http://prezi.com/b1efylil8mbs/do-the-write-thing-teaching-with-writing/ The University of Iowa | Center for Teaching | The Writing Center Carol Severino: carol-severino@uiowa.edu ; Matt Gilchrist: matthew-Gilchrist@uiowa.edu 2 Do the Write Thing: Teaching with Writing A structure for writing prompts: one right way to write an assignment Title of the assignment: You want your students to have compelling and original titles; model that practice in your prompt. Tasks: Using language that states the task explicitly, tell students what they must do in the very first sentence of the prompt. Begin the prompt with your context-specific definition of the task to help students understand how, for instance, an analysis in a course about jazz composition differs from an analysis in a rhetoric course. Discussion: Provide all of your expectations. If you have a lengthy list of things that should be included or questions that must be answered, put them in bullet-point form so they don’t get lost. Put active verbs that direct the students’ efforts in bold (e.g. select, prepare, read, critique, compare). Some of these action words are actually task genres and learning objectives in disguise! Don’t take for granted that a student knows what you mean by “critique” or how to properly “select” relevant sources. Explain these tasks and objectives in the prompt. Avoid conditional language like “you may want to” or “consider including.” Avoid ambiguous (or culturally coded) language that stands in for concrete expectations (e.g. explore, expound upon, develop your ideas about_____). Make sure that your words say what you mean. Include any information required to “set the stage,” for instance to explain the situation that the students should imagine themselves writing within or to explain that the students should write with a particular audience in mind. Make the discussion as long as in needs to be to make all of your expectations explicit. But keep it as short as possible! Purpose: Tell students what you hope they will be doing and learning. Repeat the tasks from above and connect them explicitly to your intended learning outcomes. For instance: By analyzing multiple perspectives in the controversy about prescription drug abuse, you will gain a depth of understanding about a pressing issue in the field of public health. You will also develop your skills of evaluating published research and thinking critically. Finally, this assignment is intended to help you think and write like a public health professional. Grading criteria: Students will want to know what will determine their grade, so listing your criteria or providing your rubric on the assignment sheet will help them immensely. Doing so will also help you to cross check in order to determine whether your grading criteria match your learning objectives and the purposes of the assignment. Grades should be determined primarily by the students’ performance on the stated tasks and purposes of the assignment. Formatting and other minutia: If you require specific margins and line spacing or a specific citation format, put it at the end. The assignment should be structured in a hierarchy of importance with the most important information at the top. Scaffolding assignments: A very, very long assignment prompt might suggest that you have more than one assignment rolled into a single prompt. Keep in mind that students might not have yet had the opportunity to engage in a sustained and multi-faceted writing project. Ambitious assignments are great, but students may need help approaching them in steps that build toward a final ambitious project. You might ask students to write several book reviews early in the semester, compose an annotated bibliography near the middle, create a prospectus or proposal, and then use all of this preparatory thinking and writing to compose a position paper. This suggests four writing prompts rather than one. The University of Iowa | Center for Teaching | The Writing Center Carol Severino: carol-severino@uiowa.edu ; Matt Gilchrist: matthew-Gilchrist@uiowa.edu 3