How the Indus Valley Civilization sites were

advertisement

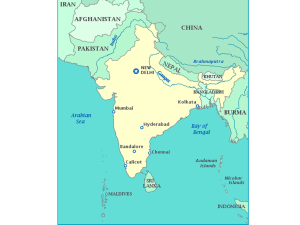

Indus Valley Civilization http://www.teachindiaproject.org/Indus_Valley_Civilization.htm Many of us are fascinated by the pyramids of Egypt and many know and relish all kinds of information and facts about that era. The remains from the Indus Valley Civilization are from roughly the same period. The Indus Valley people lived from 3500 to 1700 BCE in the Indus Valley in modern day Pakistan and India and other countries of the region. The people of this region developed a sophisticated and technologically advanced urban culture. There is archaeological evidence of urban planning, a system of uniform weights and measures, city wide drainage systems in the settlements and knowledge of metallurgy. How the Indus Valley Civilization sites were discovered In the village of Harappa (in modern day Pakistan) there was a very old ruined castle built on a hill. Nobody knew who had lived there but local legend said that it had been the home of an evil Rajah (a kind of king), who had been punished by the gods for the bad things he did, by a huge fire that burned down his castle. The ruins had stood for hundreds of years and children used to play on them. Whenever visitors came they were shown the ruins. In 1826 an English visitor called Charles Masson saw the ruins. Some years later another visitor, an archaeologist named Sir Alexander Cunningham, visited Harappa, but the ruins had been knocked down and all that was left was a huge mound of stones and rubble. Four hundred miles away from Harappa was a large area of ruined brick mounds. The people who lived nearby thought that it was a very old burial site, and called it Mohenjo-Daro or 'Mound of the Dead'. Historians used to think that the oldest cities in India and Pakistan were built in 500BCE. Charles Masson was an English traveler who visited North West India in 1823. He wrote about the things he saw: 'In Harappa a ruined brick castle with very high walls and towers, built on a hill'. In 1853 Sir Alexander Cunningham went to study the ruins in Harappa. The buildings had been completely knocked down, but he looked very carefully through everything he could see. He found some small square stones that were very polished. They had engravings of animals and designs that no-one in India had found before. In the 1920s R D Banerji found polished stone seals just like the ones at Harappa. He was excavating at Mohenjo-Daro, which was miles away near the Indus River. He found these seals in the remains of a large city and it was at least 3500 years old. Since these early excavations more and more archaeological work has been done in the Indus valley area. Thousands of settlements and some cities have been found. They all have the stone seals and artifacts just like the ones at Harappa and Mohenjo-Daro. When the British ruled India they built railways to make their lives easier. An engineer called Robert Brunton ordered workers to knock down some old walls and empty buildings. They laid the railway tracks on the stones. In 1921 the Indian government paid an archaeologist named Daya Ram Sahni, to find out more about Harappa. A trench was dug along the top of a mound. In the bottom were lots more of the stone seals like the ones Sir Alexander had found. Mr. Sahni dug further down and found seven or eight layers of houses, one on top of the other. It was an enormous city. It was also a very old city, from about 2500 BCE. This meant that it was as old as the pyramids in Egypt. The cities at Harappa and Mohenjo-Daro had streets, baths and storage for grain. In the houses archaeologists found gold and silver objects, toys made from stone and jewelry made from precious stones. Nobody knows much about the people who lived in the Indus valley 4500 years ago, but we do know they were some of the first people on earth to live in cities. 1 Reconstruction of the gate at Harappa Trade Routes 2 The Salient Features of the Indus Valley Civilization by Puja Mondal http://www.yourarticlelibrary.com/history/the-salient-features-of-the-indus-valley-civilization-history/4425/ The Harappan culture covered parts of Punjab, Sind, Baluchistan, Gujarat, Rajasthan and the fringes of western Uttar’ “Pradesh. It extended from Jammu in the north to the Narmada estuary in the South, and from the Makran coast of Baluchistan in the west to Meerut in the north-east. Image Courtesy : 3.bp.blogspot.com/-BgHVaACkNz8/TiGIUgMnQYI/sw.jpg The area formed a triangle and accounted for about 1,299,600 square kilometers. Recent Carbon-14 dating indicate the period of the mature Harappan civilization to be from C.2,800/2,900-1,800 B.C. Modern research on the Harappan civilization, establishing evidence of their contact with the Mesopotamian Civilization also corroborates this dating. Town Planning: The most remarkable feature of the Harappan civilization was its urbanization. Each city was divided into a citadel area where the essential institutions of Civil and religious life were located and the lower residential area where the urban population lived. In Mohenjodaro and Harappa, the citadel was surrounded by a brick wall. At Kalibangan, both the citadel and the lower city were surrounded by a wall. The use of baked and unbaked bricks of standard size shows that the brick making was a large scale industry for the Harappans. In the citadel area, the Great Bath at Mohenjodaro is the most striking structure. It is assumed that it was meant for some elaborate ritual of vital importance for the people. To the west of the Great Bath there are the remains of a large granary. At Harappa remarkable number of granaries has also been found ranged in two rows of six, with a central passage. In Mohenjoadro, to another side of the Great Bath, is a long building which has been identified as the residence of a very high official. Another significant building here is an assembly hall. The most significant discoveries at Kalibangan and Lothal are the fire altars. 3 The lower town was divided into wards like a chess board, by north-south and east-west arterial roads and smaller lanes, cutting each other at right angles, as in a grid system. The rectangular town planning was a unique feature of the civilization. The arterial roads were provided with covered drains having additional soak pits made of pots and placed at convenient intervals. The houses of varying sizes point towards the economic groups in the settlement. The parallel rows of two room cottages unearthed at Mohenjodaro and Harappa were perhaps used by the poorer sections of society, while the big houses, which had much the same plan- a square courtyard around which were a number of rooms – were used by the rich. The houses were equipped with private wells and toilets. The bathrooms were connected by drains with sewers under the main street. The drainage system is one of the most impressive achievements of the Harappans and presupposes existence of some kind of municipal organization. The houses were constructed with the kiln-made or Kuccha bricks, not stones. The bathrooms and drains were invariably built with pukka bricks made waterproof by adding gypsum. Agriculture: The Harappans cultivated wheat and barley, peas and dates and also sesame and mustard which were used for oil. However, the people cultivated rice as early as 1,800 B.C. in Lothal. The Harappans were the earliest people to grow cotton. Irrigation depended on the irregular flooding of the rivers of Punjab and Sind. Canal irrigation was not practiced. The evidence of a furrowed field in Kalibangan indicates that the Harappans were using some sort of wooden plough. It has also suggested that the Harappan people used a toothed harrow. Stock Breeding: No less important than agriculture was stock breeding. Besides sheet and goats humped cattle, buffalos and elephants were domesticated. The camel was rare and the horse was probably not known to the Harappans. Trade and Its Network: There was extensive inland and foreign trade. It has also been reasonably established that this trade might have been overland as well as maritime. It is proved by the occurrence of small terracotta boats, and above all, by the vast brick built dock at Lothal. As there is a no evidence of coins, barter must have been the normal method of exchange of goods. But the system of weights and measures was excellent. For weighing goods – small as well as large – perfectly made cubes of agate were employed. The weights followed a binary system in the lower denominations: 1, 2, 4, 8 to 64 and then going to 160 and then in decimal multiples of 16, 320, 640, 1,600, 3,200 etc. What they imported must have been goods locally unavailable such as copper (from South India, Baluchistan and Arabia), gold (South India, Afghanistan and Persia), Silver (Afghanistan and Iran), lapis lazuli (Badak-shan in north east Afghanistan) turquoise (Iran), Jade (Central Asia), amethyst (Maharashtra), agate, chalcedony and carnelian from Saurashtra and western India. Harappan seals and other small objects used by the merchants and traders for stamping their goods have been found in Mesopotamia. Mesopotamian literature speaks of the merchants of Ur (in Mesopotamia) as carrying on trade with foreign countries. Among these the most frequently mentioned are Tilmun, Magan and Meluhha. 4 Tilmun is most commonly identified with the island of Bahrein in the Persian Gulf-Magan may be Oman or some other port of South Arabia. Meluhha is now generally understood to mean India, especially the Indus region and Saurashtra. Crafts: The various occupations in which the people were engaged spanned a wide range – spinning and weaving of cotton and wool, pottery- making, bead-making and seal making metal working was highly skilled. They made fine jewelry in gold, bronze implements, copper beakers, saws, chisels and knives of different metals. Stone sculptures were rare and undeveloped. The Bearded Head in stone from Mohenjodaro is a well-known piece of art. Science: The Harappans knew mining metal- working and the art of constructing well-planned buildings, some of which were higher than two stories. They were also adopting at manufacturing gypsum cement which was used to join stones and even metals. They knew how to make long-lasting paints and dyes. The Indus Script: The Harappan script has not been deciphered so far, but overlaps of letters on some of the potsherds from Kalibangan show that the writing was boustrophedon or from right to left and from left to right in alternate lines. Religion: Clay figures of the mother Goddess, worshipped by the people as the symbol of fertility, have been found. A seated figure of a male god, carved on a small stone seal, has also been found. The seal immediately brings to mind the traditional image of Pasupati mahadeva. Certain trees seem to have been treated as sacred, such as the pipal. They also held the bull scared. Major Cities: Harappa: Harappa, located on the bank of river Ravi, was the first site to be excavated. It ranks as the premier city of the civilization. In Harappa, a substantial section of the population was engaged in activities other than food production – like administration, trade, craft work or religion. Mohenjodaro: Mohenjodaro, located on the bank of river Indus, was the largest Harappan city. Excavations show that people lived here for a very long time and went on building and rebuilding houses at the same location. Lothal: In Gujarat, settlements such as Rangapur, Surkotada and Lothal have been discovered. This place seems to have been an outpost for sea-trade with contemporary west Asian Societies. Decline: Around 1,800 B.C. the major cities in the core region decayed and were finally abandoned. The settlements in the outlying regions slowly de- urbanized. Some of the plausible theories for the decline of the Harappan civilization are the given here along with their pros and cons. A. Floods and Earthquakes: It has been postulated that floods and earthquakes destroyed the civilization. The theory has been criticized on various grounds: 1. Decline of settlements outside the Indus Valley cannot be explained by this theory. 2. A river cannot be damaged by tectonic effects. 5 B. Change in Course of the Rivers: Another theory (HT Lamb rick) is that Mohenjodaro was destroyed by the change in the course of river Indus away from it. The people of the city and the surrounding food producing village deserted the area because they were starved of water. According to this theory, silt observed in the city is actually the product of wind action. Criticism:This can explain only desertion of Mohenjodaro but not its decline. C. Aridity: Another hypothesis is that the increased aridity of the Indus region and the drying up of the river Ghaggar led to the decline of civilization. Though the theory is interesting, it has not yet been fully worked out. Drying up of river Ghaggar has not yet been dated. D. Aryan Invasion: Another theory states that barbarian or Aryan invasion destroyed Harappa (M Wheeler). Aryan arrival is not dated earlier than 1,500 B.C. Therefore, a Harappan and Aryan clash seems difficult to accept. E. Ecological Factors: Scholars like Fairservis tried to explain the decay in terms of the problems of ecology – that the growing demands of the centers disturbed the ecology in the semi-arid region and the area could not support them anymore. Town people moved away to Gujarat and eastern areas. This process of decline was completed by raids and attacks of nearby settlements. Criticism: Soil continues to be fertile till today in the area. More information about the needs of the Harappan towns is required before this hypothesis is substantiated. Problems in explaining Harappan decline had led the scholars to: 1. Abandon the search for causes of decline. 2. Look for continuities of Harappa in a geographical perspective. 3. Accept that the cities declined and certain traditions like seals, writing, and pottery were lost. Archaeologically speaking, the Harappan communities merged into the surrounding agricultural groups after the urban phase was over but still retained some of their traditions. Did This Ancient Civilization Avoid War for 2,000 Years? Annalee Newitz http://io9.com/a-civilization-without-war-1595540812 The Harappan civilization dominated the Indus River valley beginning about five thousand years ago, many of its massive cities sprawling at the edges of rivers that still flow through Pakistan and India today. But its culture remains a mystery. Why did it leave behind no representations of great leaders, nor of warfare? Archaeologists have long wondered whether the Harappan civilization could actually have thrived for roughly 2,000 years without any major wars or leadership cults. Obviously people had conflicts, sometimes with deadly results — graves reveal ample skull injuries caused by blows to the head. But there is no evidence that any Harappan city was ever burned, besieged by an army, or taken over by force from within. Sifting through the archaeological layers of these cities, scientists find no layers of ash that would suggest the city had been burned down, and no signs of mass destruction. There are no enormous caches of weapons, and not even any art representing warfare. That would make the Harappan civilization an historical outlier in any era. But it's especially noteworthy at a time when neighboring civilizations in Mesopotamia were erecting massive war monuments, and using cuneiform writing on clay tablets to chronicle how their leaders slaughtered and enslaved thousands. 6 What exactly were the Harappans doing instead of focusing their energies on military conquest? The Harappan People The Indus River flows out of the Himalayas, bringing fresh water to the warm, dry valley where the ancient city of Harappa first began to grow. The Harappan civilization is the namesake of this city, located between two rivers, whose arts, written language, and science spread to several other large, riverside cities in the area. Mohenjo-Daro was the largest of these cities with a population of roughly 80,000 people. Archaeologists have recently analyzed the teeth of people buried in Mohenjo-Daro's graveyards, searching for telltale chemical traces that reveal where these people drank water as children. They discovered that many had grown up drinking water from elsewhere in the region, meaning that a lot of the city's inhabitants were migrants who had come to the city as adults. Art from Harappan cities also attests to a very mixed population, with statues showing people who sport a wide variety of clothing and hair styles. So the Harappans appear to have been a very diverse lot. Some traveled far from their cities, probably by boat across the Persian Gulf, to trade with other great civilizations in the region during the 2000s BCE. There was at least one Harappan trade outpost in Mesopotamia, in the city of Eshnunna, which today lies about 30 km northeast of Baghdad. People from other Mesopotamian cities like Ur owned distinctively Harappan luxury goods such as beads and tiny carved bones. Harappans appear to have been traders who welcomed people to their cities from pretty much anywhere. But that doesn't mean they were disorganized or anarchic. Standard Measures and Writing By studying the layers of built environments in Harappa, archaeologists have pieced together a fragmentary history of the civilization's rise. Harappa began as a village, probably about 6,000 years ago. There's evidence of agriculture and very early pottery throughout the 3000s BCE. It's also during this time that we begin to see markings that look like writing on pottery. Over a period of just a couple of centuries, these crude marks evolved quickly into an alphabet that we still can't decipher. Here you can see a typical example of Harappan writing, on a seal that would have been pressed into soft clay, and was probably used in trade. Indeed, it seems that writing in Harappa followed soon after the invention of standard weights and measures for commerce. Archaeologists have unearthed hundreds of blocks in a variety of standard sizes that conform to the binary weight system favored in the Indus Valley. This fits with most accounts of how writing emerges in civilizations. Often, it begins with people using numbers and math to determine who owns what, or who has bought what from whom. From there, it develops quickly into a full-blown system of symbols. Writing seems to be one of those technological innovations that evolves very rapidly once people start using it. It's next to impossible to build an urban civilization without standard measures and writing, but it's rare that we have a chance to look back in history to glimpse a literate culture emerging from a pre-literate 7 one. In the ruins of Harappa, we can track that transition taking place. And the more writing we see in a given layer, the more complicated and advanced the civilization had become. Advanced Technologies and Civil Engineering Harappans didn't just create standardized measures — they liked everything to be standardized, right down to the size of the bricks they used to build their homes. Bricks and boards, like weights, came in just a few standard sizes. Echoing this love of order, Harappans built their cities on fairly strict grids. Above is a sketch of the city plan of Mohenjo-Daro, based on what we've been able to reconstruct from ruins. There are several wide promenades — large enough for two carts to drive side-by-side — that passed through the city, then out of the gates and into the farmlands beyond. Though the idea of a street grid seems perfectly ordinary to city-dwellers today, it was unusual at the time. Most great cities in Mesopotamia, for example, had curving streets and a more organic-looking layout. Sometimes archaeologists call the Harappan architectural style "nested" because they loved to build walls within walls. Every city was surrounded by a wall, but once inside, residents would find themselves walking past several more walled enclosures. We're not entirely sure why the Harappans designed their cities this way, but it's possible that these inner walls protected sacred areas or the estates of particularly high-status citizens. I mentioned earlier that the Harappans left no monuments to their leaders, but their walls and city layouts make it clear that they were hardly egalitarians. Homes ranged from single rooms in dormitorylike buildings, possibly for slaves, to palatial estates with dozens of rooms and multiple outdoor 8 courtyards. Harappans preferred two-story buildings, and semi-public courtyards were part of nearly every home. There were regions of Harappan cities, often in their northwest corners, that were elevated above the rest. One of these elevated areas — surrounded by walls, of course — has been excavated extensively at Mohenjo-Daro. Dubbed (somewhat incorrectly) "the citadel," it includes what some archaeologists believe is a granary, as well as large, public buildings whose uses remain mysterious. But one structure stands out, partly because its design is tied to one of the greatest technological innovations of the Harappan city. It's a public bath. You can see it above, along with the grand staircase that would have taken visitors down into its waters. The floor of the bath was built from specially-sized fired bricks, and it was surrounded by many passages and small rooms. Whether or not this particular bath was simply a public bathing site, or perhaps something more ceremonial, it was the largest version of a technology that was common throughout Harappan cities. Because, you see, Harappans had plumbing. Every home had bathrooms, many had toilets, and drainage ditches throughout their cities carried waste beyond its walls. In fact, one way we know that the Harappans set up outposts in Mesopotamia is that their cities had such sophisticated, distinctive plumbing. Perhaps, instead of making war, the Harappans were devoting their money and energy to city infrastructure planning. Below, you can see an artist's recreation of what a city's plumbing would look like. Clay pipes ran alongside city streets, and past homes. Harappans were also spending a lot of time perfecting the art of luxury goods. They made bangles, carved decorative bones, worked copper and other metals. Most of all, they crafted beads that must have been famous for thousands of kilometers, given that archaeologists have found them in far-flung Mesopotamian cities. Above are some examples of the kinds of beads made in the Indus Valley. They were carved from stones, crystals and gems — and they were polished to a fine luster. Every Harappan city that we've excavated has an area that's packed with shops where artisans and engineers crafted goods for trade. We've even found scraps of cotton, which suggests that the Harappans may have been very early cultivators of this crop that later became the foundation of many textile industries in the region. Women and Men What little we know of Harappan social life comes from statues and graves. This figurine captures a woman in mid-stride, wearing the bangles so popular in Harappan shops. Her hair is styled in an elaborate twist, and the expression on her face hovers between amused and defiant. Some have called her a "dancer," but she might just as easily be standing with arms akimbo. The archaeologists who studied the teeth of people in Harappan graves noticed an interesting pattern when it came to couples who had been buried side-by-side. Because teeth gave them clues about where 9 people were from, they knew which skeletons were from native Harappan city-dwellers. And in many instances, they found Harappan women buried with migrant men. Could this mean that Harappan people participated in a tradition where husbands came to live with the families of their wives? In nearby Mesopotamia, this practice was unknown — women became the property of their husbands, and thus went to live with their new owners. Perhaps the Indus Valley style of marriage was one way that Harappan cities were able to attract so many immigrants. Or perhaps it was a sign that women in a city like Mohenjo-Daro wouldn't have been relegated to the status of property. We simply can't ever know. Some scientists have suggested that women must have been respected as people among Harappans, because so many of the surviving statues from the Indus Valley cultures are of women. But that could be a red herring — after all, Catholic cultures in the middle ages were extremely patriarchal, though they produced some of the most beautiful and enduring portraits of the Virgin Mary. Representing women in art is not the same thing as representing them in city government. All we really know is that Harappan women often married men who came from beyond the walls of their cities. And some of them probably liked to dance. The End of Indus Valley Cities Unlike other ancient civilizations in Egypt and China, the Harappan civilization has no obvious inheritors. When people began leaving Harappan cities in the late 1000s BCE, there is no obvious route that they took. Archaeologists studying the decline of this ancient civilization point to several factors that led to its death. First, there was a rather brutal climate change that began in the early 1000s BCE. Monsoons came irregularly, and the once-fertile valley became parched. Add to this drought the fact that the cities had already been over-farming, and it's likely that starvation began driving people away from Harappa. There is also ample evidence that people in the cities were suffering from tuberculosis and other infectious diseases. The one-two punch of famine and plague left the region depopulated. The last Harappan city to be abandoned was its largest, Mohenjo-Daro. During the final centuries of its occupation, the city infrastructure began to fall apart and we see fewer examples of writing. There is also some evidence of warfare — probably on the scale of gang violence. One grave outside the city walls is full of bodies where the skulls have been smashed open. In previous centuries, head injuries from fighting were sometimes survivable — doctors often treated them with trepanation, or skulldrilling. But in the waning days of the city, people with skull injuries were dumped into mass graves. Until we decipher the Indus writing system, it's unlikely that we'll ever know precisely what brought the Harappan people together into such technologically advanced cities — nor what drove them out. But the remains of their civilization have beckoned the curious for over a century now. And with each new archaeological dig, we learn more. Perhaps, at some point, we'll even discover how the Harappans managed to escape the ravages of war for over 2,000 years. 10 Name: _______________________________________ Date: ______________ Class: ______ Indus Valley/Harappan Civilization: Read the introduction on p.1, then complete your organizer with information from ALL of the articles/sources. ONLY write on this sheet! Sketch the location of the Indus River Civilization; add two major cities Town Planning/Engineering Major Indus Valley Cities Agriculture Types of buildings found Stock animals/domestication: Plumbing Trade Partners Women and Men 11 How does the invention of writing in the Indus Valley Why can’t learn much about them from their writing compare across ancient civilizations? at this time? Citing evidence from the articles, why do you think the Harappans avoided war for nearly 2,000 years? Citing evidence from the articles, what do you think was/were the 1-2 greatest causes of the decline and end of the Indus River Civilization? 12