The Yellow River.

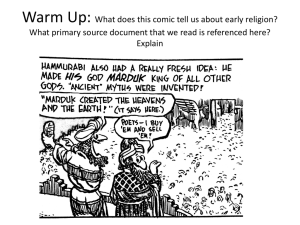

advertisement

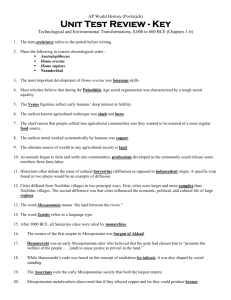

The Great River Valleys & Developing States Trade enriches. Gold-laden graves in a 6,000-year-old cemetery at Varna, Bulgaria lie by an inlet beside a woodbuilt village that is quite different from mud-walled settlements in the interior, where the graves are under the houses. The Varna culture vanished— overwhelmed perhaps by horse-tamers from the nearby steppes. Why focus on Egypt, Mesopotamia, Indus Valley, and China? • Earliest large populations • Development of monumental architecture • Development of writing – Social/economic relationships can be better understood – Religious beliefs – Political/legal systems become clearer Ecologies of Regional River Systems • • • • Nile – Regular annual flood – Abundant sunshine, few storms – Black earth – Natural boundaries Tigris and Euphrates – Irregular flooding – Violent, unpredictable storms – Region open to invaders Indus and Saraswati – Two periods of flooding annually, thus two crops possible – Monsoon – Natural boundaries, but large expanse (half million square miles) Yellow and Yangtze Rivers – Irregular floods – Loess in river replenishes nutrients in soil – Isolation because of natural boundaries of desert and mountains – Diversity of millet and grain crops (Yellow River) and rice (Yangtze River) provides greater yields, protection against famine Connections Between Ecology and Culture • • • • Egypt – God-kings, population spread along Nile River, wealthy from trade (less need for imports), developed writing and literature, rigid social/economic classes, no written laws (moral codes), belief in possible good afterlife – Stable culture, government – Regular changes in government and culture Mesopotamia – Kings governing rigidly stratified urban societies, developed writing and literature, wealth from trade (but greater need for goods from elsewhere), written laws, belief that afterlife is bad Indus Valley – Political organization unknown, writing undeciphered, urban societies (may have been independent city-states), religious beliefs unknown, internal trade and trade with Mesopotamians, highly organized cities with social stratification in some – Cities collapsed in early 2nd millennium B.C.E. China – Kings with control over religion, developed writing, feudal control over expanding territory, internal trade and wealth from abundant agriculture, social stratification – Stable culture, government “cultural divergence”? Differences in political structure, religion, trade, writing, social structure emerge alongside this move towards states. Nebamun’s tomb from the fourteenth century B.C.E. shows the Egyptian vizier hunting in the lush Nile delta, abundant in fish below his reedbuilt boat, prolific in the bird and insect life flushed from the blue thickets at his approach. He grabs birds by the handful and wields a snake like a whip. © The British Museum/Art Resource, NY Hatshepsut Diplomatic gifts. Hatshepsut’s envoy presents swords, ceremonial axes, and strung beads to the king and queen of Punt. More important, economically, than these diplomatic gifts were the vast amounts of grain and cattle the Egyptians shipped to Punt in exchange for the costly aromatic trees they acquired for the garden of the memorial temple Hatshepsut (r. c. 1503–1483 B.C.E.) was building for herself. (Fernandez-Armesto) Making bread. Some of the activities portrayed in ancient Egyptian tomb-offerings seem humdrum. Beer-making or—as in this example, nearly 3,000 years old—bread-making, are among the most common scenes. But these were magical activities that turned barely edible grains into mind expanding drinks and a life-sustaining staple food. (Fernandez-Armesto) The ziggurat of Ur. Gilgamesh, king of Uruk, hero of the world’s earliest known work of imaginative literature, shown in a relief more than 3,000 years old, kills the Bull of Heaven. The bull was a personification of drought. It was part of a king’s job to mastermind irrigation. Royal Museums of Art and History, Brussels, Belgium. Copyright IRPA–KIK, Brussels, Belgium. King Gudea (r. 2141–2122 B.C.E.) of Lagash in Sumeria, was one of ancient Mesopotamia’s most determined propagandists, distributing dozens of statues of himself to other rulers. This example is typical, with his head bound by his characteristic lamb’s fleece fillet, his overflowing oil flagon (signifying abundance under his rule), and the selfglorifying inscription that covers his robe. But the propaganda may have been born of despair. After his reign, Lagash vanishes from the historical record. (Fernandez-Armesto) Mohenjodaro Harappan seals. In the last couple of centuries, scholarly code-crackers have worked out how to read most of the world’s ancient scripts. But the writing on Harappan seals remains elusive. The seals seem to depict visions and monsters— but the messages they conveyed were probably of routine merchants, data-stock-taking and prices. In most cases that we know of, writing was first devised to record information too uninteresting for people to confide to memory. (Fernandez-Armesto) Dancing girl. One of a collection of bronze figures known as “dancing girls” unearthed at Mohenjodaro. Their sinuous shapes, sensual appeal, and provocative poses suggest to some scholars that they may portray temple prostitutes. They are modeled with a freedom that contrasts with the formality and rigidity of the handful of representations of male figures that survive from the same Civilization. Dancing girl. Bronze statuette from Mohenjo Daro. Indus Valley Civilization. National Museum, New Delhi, India. Borromeo/Art Resource, NY Harappan elite. Society and politics of ancient Harappa remain mysterious because little art survives as a clue to what went on, and we do not know how to decipher Harappan writings. A few sculptures, like this one from Mohenjodaro, depict members of an elite. The embroidered robe, jeweled crown, combed beard, and grave face all imply power—but is it priestly power, political power, or both? Andy Crawford © Dorling Kindersley, Courtesy of the National Museum, New Delhi Harappan Civilization Weighing the soul. About 4,500 years ago, Egyptian sensibilities changed. Instead of showing the afterlife as a prolongation of life in this world, tomb-painters began to concentrate on morally symbolic scenes, in which gods interrogate the dead and weigh their good against their evil deeds. (Fernandez-Armesto) The Yellow River. The powdery, wind-blown soil from inner Asia that gives the Yellow River its name is highly fertile if irrigated. In a climate slightly warmer and slightly wetter than today’s, it produced great quantities of millet in the third and second millennia B.C.E. What we now think of as Chinese civilization took shape when this region combined economically and politically with the moist, rice-producing Yangtze valley to the south. (Fernandez-Armesto) Oracle bones in China in the second millennium B.C.E. were heated until they cracked. Specialist diviners—shamans at first, later royal appointees— read the future along the lines of the cracks, scratching their interpretations into the bone. Most predictions were formal and even banal. This example says characteristically, “If the king hunts, there will be no disaster.” Connections Between Ecology and Culture Egypt God-kings, population spread along Nile River, wealthy from trade (less need for imports), developed writing and literature, rigid social/economic classes, no written laws (moral codes), belief in possible good afterlife Stable culture, government Regular changes in government and culture Mesopotamia Kings governing rigidly stratified urban societies, developed writing and literature, wealth from trade (but greater need for goods from elsewhere), written laws, belief that afterlife is bad Indus Valley Political organization unknown, writing undeciphered, urban societies (may have been independent city-states), religious beliefs unknown, internal trade and trade with Mesopotamians, highly organized cities with social stratification in some Cities collapsed in early 2nd millennium B.C.E. China Kings with control over religion, developed writing, feudal control over expanding territory, internal trade and wealth from abundant agriculture, social stratification Stable culture, government Today’s Question Is hierarchy necessary in complex human societies? Consider Hierarchy in early complex societies responded to deficiencies in communications technology and from differential control of scarce resources. Today, productive resources are sufficient to overcome scarcity. Today, global communications via the Internet can theoretically link everyone together. Modern political theory vests sovereignty in “the people” and respects the rights of all individuals. Have we created the conditions in which it is possible to put modern theory into practice and do away with hierarchical leadership? What useful functions do leaders still serve? Can we at least make access to leadership more equitable and restrict the abuse of power more effectively?