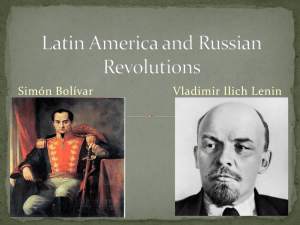

The Origins of Post-Independence Political Instability and Violence

advertisement