Item 12 - Circular Economy Update

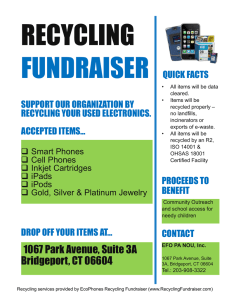

advertisement