Photosynthesis and Chemosynthesis

advertisement

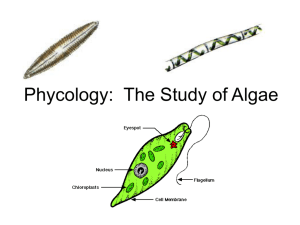

GLOSSARY March 3, 2012 LACSSP teacher workshop Photosynthesis and Chemosynthesis OXYDATION REDUCTION (REDOX): oxidation is the loss of electrons and reduction is the gain of electrons. PHOTOSYNTHETIC PIGMENTS: (http://www.ucmp.berkeley.edu/glossary/gloss3/pigments.html) Pigments are colorful compounds. Pigments are chemical compounds which reflect only certain wavelengths of visible light. This makes them appear "colorful". Flowers, corals, and even animal skin contain pigments which give them their colors. More important than their reflection of light is the ability of pigments to absorb certain wavelengths. Because they interact with light to absorb only certain wavelengths, pigments are useful to plants and other autotrophs --organisms which make their own food using photosynthesis. In plants, algae, and cyanobacteria, pigments are the means by which the energy of sunlight is captured for photosynthesis. However, since each pigment reacts with only a narrow range of the spectrum, there is usually a need to produce several kinds of pigments, each of a different color, to capture more of the sun's energy. There are three basic classes of pigments. Chlorophylls are greenish pigments which contain a porphyrin ring. This is a stable ring-shaped molecule around which electrons are free to migrate. Because the electrons move freely, the ring has the potential to gain or lose electrons easily, and thus the potential to provide energized electrons to other molecules. This is the fundamental process by which chlorophyll "captures" the energy of sunlight. There are several kinds of chlorophyll, the most important being chlorophyll "a". This is the molecule which makes photosynthesis possible, by passing its energized electrons on to molecules which will manufacture sugars. All plants, algae, and cyanobacteria which photosynthesize contain chlorophyll "a". A second kind of chlorophyll is chlorophyll "b", which occurs only in "green algae" and in the plants. A third form of chlorophyll which is common is (not surprisingly) called chlorophyll "c", and is found only in the photosynthetic members of the Chromista as well as the dinoflagellates. The differences between the chlorophylls of these major groups was one of the first clues that they were not as closely related as previously thought. Carotenoids are usually red, orange, or yellow pigments, and include the familiar compound carotene, which gives carrots their color. These compounds are composed of two small six-carbon rings connected by a "chain" of carbon atoms. As a result, they do not dissolve in water, and must be attached to membranes within the cell. Carotenoids cannot transfer sunlight energy directly to the photosynthetic pathway, but must pass their absorbed energy to chlorophyll. For this reason, they are called accessory pigments. One very visible accessory pigment is fucoxanthin the brown pigment which colors kelps and other brown algae as well as the diatoms. Phycobilins are water-soluble pigments, and are therefore found in the cytoplasm, or in the stroma of the chloroplast. They occur only in Cyanobacteria and Rhodophyta. The picture at the right shows the two classes of phycobilins which may be extracted from these "algae". The vial on the left contains the bluish pigment phycocyanin, which gives the Cyanobacteria their name. The vial on the right contains the reddish pigment phycoerythrin, which gives the red algae their common name. Phycobilins are not only useful to the organisms which use them for soaking up light energy; they have also found use as research tools. Both pycocyanin and phycoerythrin fluoresce at a particular wavelength. That is, when they are exposed to strong light, they absorb the light energy, and release it by emitting light of a very narrow range of wavelengths. The light produced by this fluorescence is so distinctive and reliable, that phycobilins may be used as chemical "tags". The pigments are chemically bonded to antibodies, which are then put into a solution of cells. When the solution is sprayed as a stream of fine droplets past a laser and computer sensor, a machine can identify whether the cells in the droplets have been "tagged" by the antibodies. This has found extensive use in cancer research, for "tagging" tumor cells. LIGHT-DEPENDENT REACTIONS: From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Light-dependent reactions of photosynthesis at the thylakoid membrane See also: Light-independent reactions The 'light-dependent reactions', or photosynthesis, is the first stage of photosynthesis, the process by which plants capture and store energy from sunlight. In this process, light energy is converted into chemical energy, in the form of the energy-carrying molecules ATP and NADPH. In the light-independent reactions, the formed NADPH and ATP drive the reduction of CO2 to more useful organic compounds, such as glucose. However, although light-independent reactions are, by convention, also called dark reactions, they are not independent of the need of light, for they are driven by ATP and NADPH, products of light. They are often called the Calvin Cycle or C3 Cycle. The light-dependent reactions take place on the thylakoid membrane inside a chloroplast. The inside of the thylakoid membrane is called the lumen, and outside the thylakoid membrane is the stroma, where the light-independent reactions take place. The thylakoid membrane contains some integral membrane protein complexes that catalyze the light reactions. There are four major protein complexes in the thylakoid membrane: Photosystem I (PSI), Photosystem II (PSII), Cytochrome b6f complex, and ATP synthase. These four complexes work together to ultimately create the products ATP and NADPH. The two photosystems absorb light energy through proteins containing pigments, such as chlorophyll. (Makes the color of leaves and trees green.) The light-dependent reactions begin in photosystem II. When a chlorophyll a molecule within the reaction center of PSII absorbs a photon, an electron in this molecule attains a higher energy level. Because this state of an electron is very unstable, the electron is transferred from one to another molecule creating a chain of redox reactions, called an electron transport chain (ETC). The electron flow goes from PSII to cytochrome b6f to PSI. In PSI, the electron gets the energy from another photon. The final electron acceptor is NADP. In oxygenic photosynthesis, the first electron donor is water, creating oxygen as a waste product. In anoxygenic photosynthesis various electron donors are used. Cytochrome b6f and ATP synthase work together to create ATP. This process is called photophosphorylation, which occurs in two different ways. In non-cyclic photophosphorylation, cytochrome b6f uses the energy of electrons from PSII to pump protons from the stroma to the lumen. The proton gradient across the thylakoid membrane creates a proton-motive force, used by ATP synthase to form ATP. In cyclic photophosphorylation, cytochrome b6f uses the energy of electrons from not only PSII but also PSI to create more ATP and to stop the production of NADPH. Cyclic phosphorylation is important to create ATP and maintain NADPH in the right proportion for the light-independent reactions. The net-reaction of all light-dependent reactions in oxygenic photosynthesis is: 2H2O + 2NADP+ + 3ADP + 3Pi → O2 + 2NADPH + 3ATP The two photosystems are protein complexes that absorb photons and are able to use this energy to create an electron transport chain. Photosystem I and II are very similar in structure and function. They use special proteins, called light-harvesting complexes, to absorb the photons with very high effectiveness. If a special pigment molecule in a photosynthetic reaction center absorbs a photon, an electron in this pigment attains the excited state and then is transferred to another molecule in the reaction center. This reaction, called photoinduced charge separation, is the start of the electron flow and is unique because it transforms light energy into chemical forms. DARK REACTION: LIGHT INDEPENDENT REACTION: From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia The light-independent reactions of photosynthesis are chemical reactions that convert carbon dioxide and other compounds into glucose. These reactions occur in the stroma, the fluid-filled area of a chloroplast outside of the thylakoid membranes. These reactions take the light-dependent reactions and perform further chemical processes on them. There are three phases to the light-independent reactions, collectively called the Calvin cycle: carbon fixation, reduction reactions, and ribulose 1,5-bisphosphate (RuBP) regeneration. Despite its name, this process occurs only when light is available. Plants do not carry out the Calvin cycle by night. They, instead, release sucrose into the phloem from their starch reserves. This process happens when light is available independent of the kind of photosynthesis (C3 carbon fixation, C4 carbon fixation, and Crassulacean Acid Metabolism); CAM plants store malic acid in their vacuoles every night and release it by day in order to make this process work.[1] Light-independent reactions The simplified internal structure of a chloroplast Overview of the Calvin cycle and carbon fixation CORRECT EQUATION FOR PHOTOSYNTHESIS—get from Nick is this correct? The overall chemical reaction involved in photosynthesis is: 6CO2 (carbon dioxide) + 12H2O (water) --> C6H12O6 (glucose) + 6O2 (oxygen gas) + 6H2O (water) CHROMOTOGRAPHY Main article: History of chromatography Thin layer chromatography is used to separate components of a plant extract, illustrating the experiment with plant pigments that gave chromatography its name Chromatography, literally "color writing", was first employed by Russian scientist Michael Tsvet in 1900. He continued to work with chromatography in the first decade of the 20th century, primarily for the separation of plant pigments such as chlorophyll, carotenes, and xanthophylls. Since these components have different colors (green, orange, and yellow, respectively) they gave the technique its name. New types of chromatography developed during the 1930s and 1940s made the technique useful for many separation processes. Chromatography technique developed substantially as a result of the work of Archer John Porter Martin and Richard Laurence Millington Synge during the 1940s and 1950s. They established the principles and basic techniques of partition chromatography, and their work encouraged the rapid development of several chromatographic methods: paper chromatography, gas chromatography, and what would become known as high performance liquid chromatography. Since then, the technology has advanced rapidly. Researchers found that the main principles of Tsvet's chromatography could be applied in many different ways, resulting in the different varieties of chromatography described below. Advances are continually improving the technical performance of chromatography, allowing the separation of increasingly similar molecules. CHEMOSYNTHESIS: http://www.pmel.noaa.gov/vents/nemo/explorer/concepts/chemosynthesis.html Chemosynthesis is the process by which certain microbes create energy by mediating chemical reactions. From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Chemosynthesis In biochemistry, chemosynthesis is the biological conversion of one or more carbon molecules (usually carbon dioxide or methane) and nutrients into organic matter using the oxidation of inorganic molecules (e.g. hydrogen gas, hydrogen sulfide) or methane as a source of energy, rather than sunlight, as in photosynthesis. Chemoautotrophs, organisms that obtain carbon through chemosynthesis, are phylogenetically diverse, but groups that include conspicuous or biogeochemically-important taxa include the sulfur-oxidizing gamma and epsilon proteobacteria, the Aquificaeles, the Methanogenic archaea and the neutrophilic iron-oxidizing bacteria. Many microorganisms in dark regions of the oceans also use chemosynthesis to produce biomass from single carbon molecules. Two categories can be distinguished. In the rare sites at which hydrogen molecules (H2) are available, the energy available from the reaction between CO 2 and H2 (leading to production of methane, CH4) can be large enough to drive the production of biomass. Alternatively, in most oceanic environments, energy for chemosynthesis derives from reactions in which substances such as hydrogen sulfide or ammonia are oxidized. This may occur with or without the presence of oxygen. Many chemosynthetic microorganisms are consumed by other organisms in the ocean, and symbiotic associations between chemosynthesizers and respiring heterotrophs are quite common. Large populations of animals can be supported by chemosynthetic secondary production at hydrothermal vents, methane clathrates, cold seeps, and whale falls. It has been hypothesized that chemosynthesis may support life below the surface of Mars, Jupiter's moon Europa, and other planets.[1] Giant tube worms use bacteria in their trophosome to react hydrogen sulfide with oxygen as a source of energy. Some reactions produce sulfur, such as: Hydrogen sulfide chemosynthesis: CO2 + O2 + 4H2S → CH2O + 4S + 3H2O (CH2O is used to mean carbohydrate, not formaldehyde.) Instead of releasing oxygen gas as in photosynthesis, solid globules of sulfur are produced. In bacteria that can do this, such as purple sulfur bacteria, yellow globules of sulfur are present and visible in the cytoplasm. Discovery In 1890, Sergei Nikolaevich Vinogradskii (or Winogradsky) proposed a novel life process called chemosynthesis. His discovery suggested that some microbes could live solely on inorganic matter and emerged during his physiological research in the 1880s in Strassburg and Zurich on sulfur, iron, and nitrogen bacteria. This was confirmed nearly 90 years later, when hydrothermal ocean vents were predicted to exist in 1970s. The hot springs and strange creatures were discovered by Alvin, the world's first deep-sea submersible, in 1977 at the Galapagos Rift. At about the same time, Harvard graduate student Colleen Cavanaugh proposed chemosynthetic bacteria that oxidize sulfides or elemental sulfur as a mechanism by which tube worms could survive near hydrothermal vents. Cavanaugh later managed to confirm that this was indeed the method by which the worms could thrive, and is generally credited with the discovery of chemosynthesis.[citation needed] A 2004 television series hosted by Bill Nye named chemosynthesis as one of the 100 greatest scientific discoveries of all time.[2]