Pablo Sanguinetti[·] - Departamento de Economía

advertisement

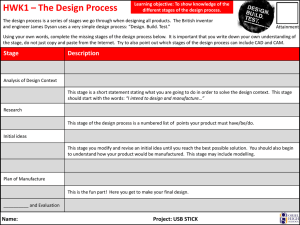

![Pablo Sanguinetti[·] - Departamento de Economía](http://s3.studylib.net/store/data/005909182_1-a5e7469e63ba12dc1ec7a51c45e4d2f0-768x994.png)