"It\`s Alive!" Fossil Activity

advertisement

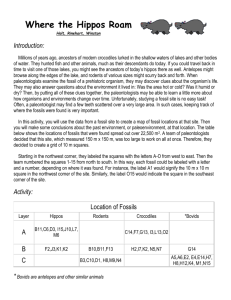

Title: “It’s Alive!” Fossil Activity Author: Dr. Peg Yacobucci Associate Professor Department of Geology Bowling Green State University 190 Overman Hall Bowling Green, OH 43403 419-372-7982 mmyacob@bgsu.edu Context: This activity is the first lab exercise students do. Each student selects a fossil, describes and sketches it, and then must write out a "proof" that this object represents a once-living animal, rather than a mere rock or mineral formation. In addition to getting students comfortable handling fossils and encouraging them to observe closely, the activity leads students towards an understanding of uniformitarianism. Goals: In this activity, students will learn about: The types of features typically preserved on a fossil The idea that “the present is the key to the past” – that comparing fossils to living organisms is a powerful approach for understanding fossils The historical origins of modern paleontology They will also gain experience in: Creative problem solving Touching and picking up a fossil specimen Observing fossil specimens closely Expressing these observations in both words and pictures Role playing Description: The first lab activity for the course is called “Paleontology—Past, Present, and Future”. In addition to discussing several documents related to present and future research directions in the field, students review a brief timeline of the historical development of paleontology as a science. Then they get their first opportunity to work directly with fossils. Students are presented with a set of fossil specimens in boxes (with no identifying labels). Each student selects one fossil of their own. They are asked to make and record very close, detailed observations of the specimen, and to sketch the fossil. Then they are told to “think like it’s 1600.” Someone has brought this object, taken out of the local rocks, for the student to investigate. The student must write a “proof” that this fossil was obviously once alive, and is not just an interesting mineral or rock formation. They can use their observations, compare the specimen to other objects with which they’re familiar, resort to pure logic, or apply any other avenue of argumentation they think will help make their case. Note: In the next lab, on fossil preservation and taphonomy, the students revisit their fossil specimen, and determine its mode of preservation. Indeed, the student’s “pet fossil” could be used throughout the course to illustrate various components of the course content. Evaluation: The exercise is evaluated on three components: Depth and level of detail in the student’s description of the specimen Care taken in making the sketch (although artistic ability is downplayed, attention to detail is important) Thought shown in, and creativity of, the student’s proof GEOLOGY 415/515 Paleontology Lab 1 Paleontology—Past, Present, and Future Look over the set of fossil specimens laid out on the table. Choose one specimen, write your name on a paper label, and place the label in the specimen’s box. Let’s begin by looking closely at your fossil. Examine the specimen carefully, and write out a description of it. Include things like its color, size, shape, and texture, and a list of the major features you can see. Next, make a few detailed sketches of your fossil. You might sketch it from several different sides, for instance. While your artistic talent will not be graded, be sure that you’re showing all the details you think might be important. Also, indicate the size of the specimen. Now imagine that the year is 1600. Your neighbor, knowing that you’re a modern, 17th Century kind of person who’s interested in such puzzles, has just brought you this specimen. She reports that she found it embedded in a rock face on the outskirts of town. While your neighbor thinks this object is just an interestingly-shaped rock, you suspect otherwise. Write a “proof” that this object was obviously once a living organism, and is not just an interesting mineral or rock formation. You might refer to your description and sketches, compare the specimen to other objects with which you’re familiar, use pure logic, or any other argument you think will help make your case.