Capital Budgeting and Risk

advertisement

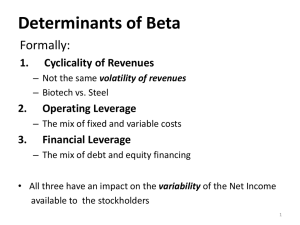

9 Capital Budgeting and Risk INTRODUCTION One of the most common and important applications of the CAPM involves estimation of the company cost of capital and required return for projects. Chapter 9 describes this application in detail. It is important to remember that the required rate of return on a project is a function of the risk of the project and does not depend on whom or which company undertakes it. The risk of the project, which is relevant, is, of course, its market risk or beta and not the total risk. A company’s stock beta and its cost of capital reflect the nature of all its assets as well as the financial leverage or the debt it carries in its balance sheet. Using the company cost of capital as the discount rate for all its new projects would be a serious error. Nevertheless, we may still want to know what return is expected from the securities of a company. From this, we can work out what return is required from projects whose risks are similar to those of the company's existing business. Riskier projects should have a higher hurdle rate and safer projects a lower cutoff rate. The chapter also discusses estimation of betas for companies using market information and the relationship between beta, financial leverage, and operating leverage. We can estimate the beta of a stock by comparing the stock’s returns over time against the market returns. However, individual company beta estimates tend to be unstable and it is often better to calculate the beta for the industry group to which the company belongs. Other related topics covered in the chapter include the risk and betas for foreign projects and the common, but often erroneous, practice of using arbitrary risk premiums (fudge factors) to adjust for projects considered risky. The concept of certainty equivalent, an alternate approach to adjust for the risk of cash flows, is also explained in this chapter. Most of the discussions on risk-adjusted returns in the chapter use the CAPM as the theoretical risk-return model. The basic principles covered apply to alternate models like the APT or the three-factor model as well. KEY CONCEPTS IN THE CHAPTER Project Risk, Required Rate of Return, and Cost of Capital: We have already learned that diversified investors require returns on their investment based on the market risk or nondiversifiable risk of their investments. The required rate of return on a project should thus be a function of only its market risk or beta. It should not make any difference as to which company undertakes the project. This follows directly from the CAPM and the value additivity principle. Thus, the discount rate used to evaluate a project should be estimated using the project’s beta. 95 Cost of capital for a company is the required rate of return demanded by the investors on the securities issued by the company. In practice, this is the weighted average of the return on the company’s securities, typically debt and equity. Companies estimate their cost of capital using market data and use this company cost of capital as the discount rate for evaluating new projects. Typically the estimated beta is used to compute the cost of equity capital using the CAPM formula: r = rf + (rm - rf). This cost of equity is appropriate and correct only if the project under consideration is exactly like the existing operations of the company, which is unlikely to be the case for any company with more than one type of business. Please remember that required rate of return demanded by investors depends on the use to which the capital is put. This does not mean that company cost of capital estimates have no practical value. In fact, they are extremely useful in estimating market’s assessment of the required rate of return on the typical mix of the company’s assets. Thus, for any project, which is of comparable risk, the company cost of capital might be a very good measure. For projects, which have higher risk, a higher discount rate will need to be used and projects, which have lower risk, should be evaluated with lower rate of return. Estimating Beta for a Project: The required rate of return for a project depends on its systematic risk and is measured by its beta. The problem of choosing a suitable discount rate for a project therefore amounts to working out what sort of beta it has. We cannot do this directly because individual investment projects are not traded in the New York Stock Exchange. The best approximation is obtained by estimating the betas of companies, which are in the same business as the project. If one can estimate the betas for a number of companies in an industry and then estimate an average beta for the industry, this will be a reliable estimate for the industry represented by the companies. The beta of a company's stock measures how its price responds to market movements and is estimated by plotting returns on the stock against returns on the market index. Monthly returns are commonly used and the slope of the fitted line through the scatter of points is the beta of the stock. The line is often referred to as the characteristic line for the stock. One can also use published betas produced by a number of brokerage and advisory services. Standard and Poor and Merrill Lynch, among others, publish information on betas. It is important to note that estimates of individual company betas are highly unstable and it is better to use industry betas with any adjustment for financial leverage as discussed later. A beta, calculated for an industry group, would generally provide a more accurate measure of the beta of a project than that of the estimate for a single company. The typical information published with beta include the following: - Beta: the regression-analysis estimate of beta - Alpha: the intercept of the fitted regression line - R2: the proportion of the variance of price changes explained by market movements - Residual standard deviation: the standard deviation of the unique risk of the stock 96 - Standard errors of beta and alpha: measures of the probable accuracy of these estimates - Adjusted beta: the earlier estimate adjusted to take account of the effect of estimation errors. The R2 gives the percentage of the variance of the stock returns explained by the market return or a measure of its market risk. A stock with an R2of 35 percent has 65 percent unique risk. Thirty five percent of its risk is market risk. Beta and Financial Leverage: The beta of a project in a strict sense should reflect its business risk. The typical beta measured using stock returns reflect not only the business risk, but also the effect of any financial leverage or borrowing of the company. When a company borrows money it increases the risk of the stockholders. Thus, other things equal, financial leverage increases the risk of the company and the beta of a stock with leverage will be higher than the pure asset beta. We can derive the effect of leverage on beta using the relationship: Value of assets = value of equity + value of debt with all the values measured in market values. The beta of a portfolio is the weighted average of the individual security betas. Consider the company's assets as financed by a portfolio of liabilities or sources of funds, i.e. partly by equity and partly by debt. Therefore, the beta of the assets should equal the beta of the weighted average of the betas of the liabilities. equity debt debt x V V where V = equity + debt assets = equity x The beta of debt is often very close to zero. Therefore, we can rewrite the relationship as: assets equity x equity V equity assets x V equity These equations can be used to calculate the beta of assets from the market-estimated beta of a leveraged company stock. Example: ABC Corp. stock has a beta of 1.3. The company has a debt/assets ratio of 30 percent. Assuming the debt beta to be zero, assets 13 . x 0.7 0.91 What will happen if the company reduces its debt to 20 percent of assets? Again, we can use the 97 relationship above to figure out the beta for the stock. V equity assets x equity 1 equity 0.91x 114 . (1 0.2) The impact of leverage on beta and the cost of capital presented in this chapter ignores the effect of taxes. We will deal with that in Chapter 19. Betas and Discount Rates for International Projects: The conventional wisdom on overseas investments is that they are generally riskier than investments in one’s own country. This perception is based on the general feeling that things get more uncertain when one leaves one’s home country. However, this ignores the fact that the risk that matters should be the nondiversifiable risk that is measured by beta and that beta is a function of not only the standard deviation of the project’s cash flows but also the correlation of the project’s cash flows to the domestic market returns. While the standard deviation for foreign projects can be higher than their domestic counterparts, it is also generally true that the correlation of such projects are a lot less than a comparable domestic project will have to the domestic market return. Thus, it does not automatically follow that foreign projects will have higher betas and should be evaluated at higher discount rates. One should analyze both the standard deviation and the correlation of the project to domestic market returns. This will apply to a foreign company undertaking a project in the U.S. as well. Cost of Capital Across Countries: It is a mistake to compare interest rates and costs of capital across countries without adjusting for the differences in inflation. The nominal interest rates across countries will differ because of the differences in inflation. Thus, the fact that interest rates in Japan are 3 percentage points lower does not mean that it is cheaper to borrow in Japan and Japanese companies enjoy a lower cost of capital advantage. One has to compare the real interest rates before making any judgement. Of course, it is possible that the savings and therefore, the supply of loanable funds could be different and relatively large in one country relative to the demand for loans. In such a case, the country could have a lower real rate. This line of argument assumes that capital does not easily flow across borders; an assumption not too realistic in an increasingly global economy. Arbitrary Discount Rates: Corporate managers often face the task of setting discount rates for projects which are different from the typical project handled by them. These projects may be considered riskier than normal and are often evaluated with an arbitrary and higher discount rate than normal. The higher discount rate may be assigned to cover for an imprecise cash flow estimate and/or for the perceived higher uncertainty surrounding the project. One needs to think through the nature of the risk involved and distinguish between systematic and unique risk. The question is not simply what makes an asset's future earnings uncertain. What matters is the extent to which abnormally low earnings are likely to coincide with low earnings in the economy as a whole. It is also better to sort out the cash flow estimation problems by correcting the estimates rather than add an arbitrary risk premium for a vaguely defined risk. High discount 98 rates heavily penalize projects with cash flows in later years of the project’s life. Cyclicality, Operating Leverage, and Beta: High standard deviation of earnings does not necessarily mean high beta. What matters are the earnings variability and its relationship to the market returns. Cyclical firms, whose earnings are strongly dependent on the state of the business cycle, tend to have high betas. Variability of earnings can be due to unique risk. A strong relationship between a firm's earnings and aggregate earnings means high market risk. The accounting beta or the cash-flow beta can be used to measure this. These betas are estimated using the accounting earnings or cash flows instead of security returns. Beta is also a function of the operating cost structure. Other things equal, higher fixed costs will mean higher beta. The high level of fixed cost produces a leverage effect which makes profits particularly vulnerable: a small percentage change in revenues will produce a much larger percentage change in profits. Companies with high fixed costs (often called high operating leverage) tend to have high betas. The relationship can be expressed as follows: asset revenue 1 PV ( fixed cos t ) Pv(asset ) Certainty-Equivalent Cash Flows: The standard approach for calculating present value of a stream of uncertain cash flows is to discount the cash flows using a risk-adjusted rate derived from the CAPM or some other risk-return model. That is: n Ct t t 0 (1 r ) NPV where r rf ( rm rf ) . This procedure would be inappropriate for a project whose beta is expected to vary through time. In such cases, it is better to use the certainty equivalent cash flows (CEQ) which are cash flows fully adjusted for the risk involved so that they can be discounted using the risk-free rate. Thus, the NPV can be written as: n NPV t 0 CEQt (1 r f ) t The certainty equivalent CEQt is some fraction of the expected cash flow Ct. The two methods must give the same present value, so n CEQt NPV t = t 0 (1 r f ) n Ct t = t 0 (1 r ) 99 (1 r f ) Ct t x (1 r ) t t 0 (1 r f ) n t CEQt = atCt, where at = (1 r f ) t (1 r ) t The certainty equivalent approach is suited for projects where cash flows have uneven risk through the life of the project, so that using one constant discount rate will lead to incorrect decisions. WORKED EXAMPLES 1. J. B. McIntosh is interested in finding the appropriate discount rate for its new project for making blue, pink, red and yellow widgets. The average beta of a group of colored widget manufacturers is 1.4 and their average debt-equity ratio is 0.30. McIntosh plans to have a debt-equity ratio of 0.20. If the risk-free rate is 6 percent and the expected risk premium on the market portfolio is 9 percent, what is: (a) the required return for the project and (b) the required return on the shares of the company? SOLUTION The average beta of the shares of the other widget manufacturers is 1.4. Debt to equity ratio of 0.3 means debt/assets = 0.3/1.3 = 0.23. Equity/asset = 1 - 0.23 = 0.77. Assuming beta for debt is zero, equity asset equity x 1.4x 0.77 1.08 V Required rate of return for the project = 6 + (1.08 x 9) = 15.72 percent Debt/asset ratio for McIntosh = 0.2/1.20 = 0.17, Equity/asset = 1 - 0.17 = 0.83 1 1.30 Beta of the shares of McIntosh = 1.08x 0.83 Return on McIntosh shares = 6 + (1.30 x 9) = 17.7 percent 2. Jale Breaker Inc. is considering a project, which requires an investment of $100,000 now to buy the exclusive rights to a new high tech prison security system from Victor Conway. The security system is still under trial. The results of the trial will be known next year. The experts associated with the project feel that there is a 50 percent chance that the trials will be successful. If found successful, Jale Breaker Inc. will be required to invest $2,000,000 to install the system in prisons in 20 states. The project will generate a cash flow of $500,000 forever, starting from year 2. Typical prison security system companies have a beta of 1.2. The risk free rate is 6 percent and the market risk premium is 9 percent. The cost of capital for the typical project is thus estimated at 16.8 percent. Mr. Breaker, CEO of the company, feels that the project has very high risk and therefore wants to discount the cash flows from the project using a rate of 34 percent (double the normal rate). Calculate the NPV of the project using the 34 percent discount rate. Is there a more appropriate way to evaluate the project? 100 SOLUTION NPV using 34 percent discount rate = 100,000 2,000,000 500,000 / 0.34 = -$495,083 134 . 134 . A more appropriate approach will be to evaluate the project in steps. The cash flows from the $2,000,000 investment made next year have the same risk as other security system projects or the discount rate for this should be: r r f (rm r f ) = 6 + (1.2 x 9) = 16.8 percent. The NPV of the investment of $2,000,000 will then be: NPV = 2,000,000 500,000 = $976,190 0168 . There is a 50 percent chance of this happening. That is, for the initial investment of $100,000, the company will get either zero (the trial fails) or $976,190 (trial succeeds). Thus, the overall project NPV for the initial investment of $100,000 is: NPV = 0.5( 100,000 976,190 ) 367,890 1168 . SUMMARY This chapter deals with the application of CAPM to practical capital budgeting problems. These problems include estimation of required rates of returns for projects and cost of capital. The chapter stresses the essential element of the CAPM – the risk that matters is the non-diversifiable risk. Thus, the required return on any investment should be related to this risk component and not the total risk. The chapter also points out the fact that the required rate of return on a project will depend on its market risk and not who undertakes the project. It is a mistake to use the company cost of capital to evaluate all the projects undertaken by a company. The company cost of capital reflects the mix of assets the company has and the only project to which one can apply the company cost of capital are those which are mirror images of the company’s existing operations. Estimation of a company’s stock beta involves determining the relationship between the stock’s returns and the market returns. This is easily accomplished by plotting the two sets of returns on a graph and calculating the slope of the fitted line. It is important to note that the estimated beta reflects the business risk of the company’s assets and the financial risk of the company. Higher leverage or borrowings lead to a higher beta. The asset beta reflecting the pure business risk of the assets can be derived from the stock beta. The relationship can be used to find betas at different levels of leverage. The common perception that international projects are riskier ignores the fact that international projects often have lower correlation to the domestic market returns than their domestic counterparts. This results in a lower beta, even though the variance of cash flows might be 101 higher. This assumes that each country’s investors have a predominantly domestic bias and their market portfolio essentially comprises their home country stocks. The chapter also discusses the common but erroneous practice of adding fudge factors to account for perceived risks. The fudge factors are arbitrary risk premiums and in many cases reflect nonsystematic risk. They are also often used for the correction of cash flow estimation problems. One should look at the factors causing the risk and try to identify the effect they will have on the project’s beta. Remember that beta is a function of not only the project cash flows’ variance, but also the correlation of these cash flows to market returns. Other things equal, a non-cyclical project will have a lower beta compared to a cyclical project. The standard approach to project evaluation uses a risk-adjusted discount rate for discounting all cash flows. This assumes that the project’s cumulative risk increases at a constant rate. There may be projects that have cash flows whose risk does not increase steadily. For such projects, the certainty equivalent approach might be preferable. This allows separate risk adjustment for cash flows of different periods. LIST OF TERMS Accounting beta Alpha Business risk Cash-flow beta Certainty equivalent Company cost of capital Cyclical Financial leverage Financial risk Industry beta Operating leverage Project beta Risk-adjusted rate EXERCISES Fill-in Questions 1. The use of the _______________________ as a discount rate ignores differences in the risk of projects. 2. The discount rate for evaluating a capital budgeting proposal should be derived from the ___________. 3. ____________________ measures the average rate of price appreciation on a stock in the past, when investors in the market as a whole earned nothing. 4. When a company raises debt finance, it increases the ________________________ borne by its shareholders. 5. The cost of capital depends on the ________________________ of the firm’s investments. 102 6. Financial risk is produced by_____________________ leverage. 7. Companies with high fixed costs have high _____________________. 8. A firm whose revenues and earnings are strongly dependent on the state of the business cycle is said to be a firm. 9. We can measure the strength of the relationship between a firm's earnings and the aggregate earnings on real assets by estimating either its _________________________ beta or its ________________. 10. Instead of discounting the expected value of a cash flow by its__________, we may discount its _____________________ at the risk-free rate. 11. The beta of a portfolio of stocks drawn from a single industry is called a(n) ____________. Problems 1. A firm is considering the following projects: PROJECT A B C D BETA 0.7 1.4 1.8 0.9 EXPECTED RETURN, % 13 16 21 15 The firm’s cost of capital is 16 percent. The risk-free rate is 6 percent and the expected market risk premium is 9 percent. a. Which projects will be accepted if the firm’s cost of capital is used? b. Which projects should be accepted ? 2. CBC Corp. is considering investing in two new projects. Project A is estimated to give a return of about 14%. The estimated standard deviation for the cash flows from the project is 30% and the correlation coefficient of the cash flows to market returns is 0.4. The standard deviation for the market returns is 15%. The expected market return is 14% and the risk free rate is 5%. The CEO of the company has decided that the project is not a good investment because of its "high risk" as measured by the standard deviation. The CEO does like Project B which is expected to give a return of 20% with the same standard deviation of cash flows as Project A. The correlation coefficient for this project’s cash flow with that of the market is estimated at about 0.9. Is the CEO right? Is Project B a better investment than project A? Explain your answer to the CEO. 3. Dummy Corp. stock has the following characteristics: 103 Adjusted beta Alpha 1.33 - 0.56% per month a. How much would the stock tend to go up in a month in an unchanged market? b. How much would the stock tend to go up in a month when the market went up 10 percent? 4. MetaMarket Inc. stocks have a total market value of $50 million and debt of $30 million. The current Treasury bill rate is 6 percent, and the expected market risk premium is 9 percent. A plot of the returns on the stock against the market returns shows a scatter of points through which a line can be fitted with a slope of 45. a. What is the company’s financial leverage? b. What is the beta of the stock? c. What is the beta of the company’s assets? 5. MetaMarket Inc., of problem 4, now decides to invest $20 million in additional assets that are similar to its existing assets. It decides to finance this investment by borrowing a further $20 million of debt. a. What is the beta of the additional assets? b. What discount rate should be used for these additional assets? c. What is the beta of the stock after the debt issue? 6. The market value of the shares of Astrofab Corp. is currently $24 million, and their beta is 1.4. Astrofab has a nominal $6 million of 8 percent coupon debentures outstanding which mature in 7 years. These debentures have a beta of 0.1, and they currently yield 10 percent. What is the beta of Astrofab's assets? 7. Other things being equal, which company (from each of the following pairs) do you think should be using the higher discount rate in its capital budgeting? a. (i) A steel company, (ii) a brewing company b. (i) a manufacturer of recreational vehicles, (ii) a mining company c. (i) a company with high operating leverage, (ii) a company with high financial leverage d. (i) a manufacturer of office equipment, (ii) an electric utility company. 8. A project is expected to generate net cash flows of $1,000 in each of years 1 and 2. Its beta will be 1.5 throughout its life. The risk-free interest rate is 6 percent, and the expected return on the market is 15 percent. Calculate: a. the present value of the cash flows b. the certainty equivalents of the cash flows c. the ratios of the certainty equivalents to the expected cash flow (that is, a1 and a2). 9. NFL Inc. is expanding its business in Europe. It is evaluating projects in 3 countries with details as follows: Country Project standard Correlation of project returns to deviation US market returns 104 Country A Country B Country C Country D US project 36 percent 28 percent 42 percent 22 percent 18 percent 0.4 0.6 0.2 0.8 0.9 The standard deviation of U.S. market returns is 14 percent. Calculate the beta for evaluation of the projects in each country. Essay Questions 1. Write a short memorandum describing how you will set discount rates for projects with different risks. 2. Your company uses the DCF rate of return to appraise new investment projects in the following way: a. Projects with paybacks less than 3 years are accepted if their DCF rate of return exceeds 12 percent. b. Projects with paybacks longer than 3 years are accepted if their DCF rate of return exceeds 16 percent. Discuss the advantages and disadvantages of this rule. 3. Describe how you would calculate the cost of capital of a company using the CAPM. 4. Explain why foreign projects need not necessarily have a higher discount rate than their domestic counterparts. 5. Explain the difference between the use of risk-adjusted discount rates and certaintyequivalent cash flows. Give an example of a situation where you think the certaintyequivalent method is preferable. ANSWER TO EXERCISES Fill-in Questions 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. Company cost of capital Project beta Alpha Financial risk Business risk Financial 7. Operating leverage 8. Cyclical 9. Accounting, cash-flow beta 10. Risk-adjusted rate, certainty equivalent 11. Industry beta Problems 105 1. a. Only B and C will be accepted. A and D will be rejected. b. The company should use risk-adjusted rates based on project betas. The risk-adjusted rates based betas for the different projects are: A = 12.3 percent, B = 18.6 percent, C = 22.2 percent, and D = 14.1 percent. B and C have returns less than their required rates of return; so they should be rejected. A and D have returns higher than the required rates and should be accepted. 0.4 x 30 0.9 x 30 0.8 ; Beta for Project B = 18 . 15 15 Based on the betas, the required rates of returns for the projects will be 12.2 percent and 21.2 percent. This shows that project A gives a return higher than its required rate of return, while project B does not clear its hurdle rate. 2. Beta for Project A = 3. a. -0.56 percent. b. r = 056 . 133 . x10 12.74 percent 30 0.375 ; b. Beta = 1; c. You can calculate 30 50 equity 1x (1 0.375) 0.63 (assumes the beta of assets using the relationship: asset equity x V beta of debt = 0) 4. a. The financial leverage = debt/assets = 5. a. Beta = 0.63. b. Discount rate = 6 + (0.63 x 9) =11.67 percent. c. beta = 0.63x 100 126 . 50 6. Value of debt: market price per bond x 6000 bonds = $902.63 x 6,000 = $5.42 million Value of equity: $24 million Total market value of firm = value of debt + value of equity = 5.42 + $24.00 = $29.42 million assets debt x debt equity equity x 01 . x 018 . 14 . x 0.82 116 . V V 7. a. i; b. i; c. i; d. i 8. a. Using r =6 + 1.5(15-6) = 19.5 percent, PV = $1,537.09 b. Certainty - equivalent cash flows are $887 and $786.80. c. a1 = 1.06/1.195 = 0.9016 and a2 = (1.06/1.195)2. 9. The betas for the different country projects are: A = 1.03; B = 1.2; C = 0.6; D = 1.26; Beta for the U.S. project = 1.16 106