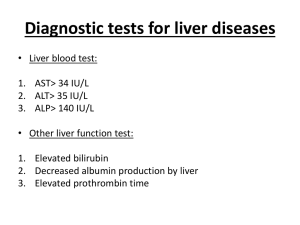

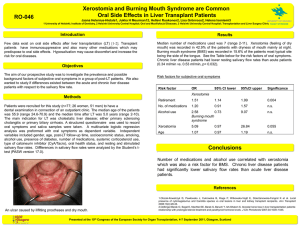

Alcoholic Liver Diseases and Alcohol Dependency

advertisement