A study of the flow-dependence of background error

advertisement

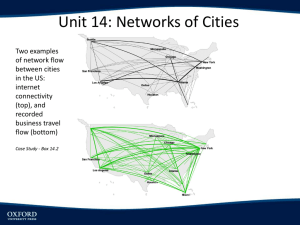

A study of the flow-dependence of background error covariances based on the NMC method Harald Anlauf, Werner Wergen, and Gerhard Paul Deutscher Wetterdienst, Offenbach, Germany E-Mail: harald.anlauf@dwd.de The NMC method, i.e., using differences of short-range forecasts verifying at the same time but with different starting dates as proxies for background error, was applied to the global model GME at DWD. The aim was to explore the variability of the background error covariance matrix B with respect to region, altitude, season, and flow pattern. The method was first applied univariately to the mass, humidity and wind field and then extended to study multivariate aspects. We present results for the years 2003 and 2004 and discuss the implications our findings will have for the modeling of the B-matrix. 1. Motivation Modern data assimilation systems such as the 4D-Var and the Ensemble Kalman Filter (EnKF) use the dynamics of the forecast model to evolve the covariance matrix of background error, B, in time either implicitly (4D-Var) or explicitly (EnKF). As a consequence, these schemes effectively use flow-dependent structure functions, although at correspondingly high computational costs. Nevertheless, the initial B-matrix still has to be specified, like for any simpler assimilation system (e.g., OI, 3D-Var). The 4D-Var also does not transfer the full dynamical background covariances to subsequent assimilations. 2. Method In order to explore the variability of the B-matrix with respect to flow pattern explicitly, we applied the NMC method at DWD to the global model GME (Majewski et al. 2002). The NMC method (Parrish and Derber 1992) uses differences of short-range forecasts verifying at the same time but with different starting dates as proxies for background error. It assumes that the spatial structure of background error does not strongly vary with forecast time, so that correlations obtained from forecast differences are reasonable approximations to the true background error correlations, at least for the mid-latitudes. covariances was performed with forecasts interpolated to a regular grid and with zonal averaging. For an assessment of seasonal variations we also used the forecasts for the summer periods of 2003 and 2004. Our investigation began with a study of the isotropic part of the empirical horizontal correlation of the 500 hPa geopotential height at 45°N using the full sample of forecasts for winter 2003/2004, shown as the blue curve in figure 1. For the exploration of the flow-dependence, we took the 24h forecast of the local 500 hPa height as an indicator for the meteorological situation. Based on the statistics of the 500 hPa geopotential height at fixed latitude over the whole period, we distributed the contributions into three classes of approximately equal sample sizes. For this forecast sample and at 45°N, a data point was associated with a region of “high” and “low” pressure if z(500 hPa) > 5527 gpm and z(500 hPa) < 5371 gpm, respectively, otherwise it was assigned to the “neutral” class. 3. Results The main results of the present study are based on the differences of 48h and 24h forecasts verifying at 00Z during the winter period from Dec. 1, 2003, until Feb. 29, 2004. The forecast fields were taken from the archived main runs of the operational GME model. The evaluation of Fig. 1: Flow-dependence of the 500 hPa horizontal geopotential correlation at 45°N, winter 2003/2004. The resulting horizontal correlation functions obtained from contributions in the classes “high” and “low” are shown in figure 1 as green and red curves. Clearly the correlations for "highs" are significantly broader than for "lows". While the above result appears quite simple, its implementation is actually non-trivial. Any attempt to modify the B-matrix in order to take into account flow-dependence has to respect symmetry and positive-definiteness constraints (Riishøjgaard 1998). The dynamical B-matrix therefore cannot be a function of the meteorological situation at only one point, it must be a function of the flow at both points. However, for the present study we ignored the latter dependence. A related quantity that depends on one point only and still provides some insight is given by the the standard deviation of the 48h-24h forecast difference. Figures 2 and 3 show the meridional distribution for the 500 hPa height, indicating that the standard deviations at mid-latitudes on the northern hemisphere are roughly 50% higher for “lows” than for "highs" during the winter period (fig. 2), and up to 60% higher during summer (fig. 3). Analogous results are obtained on the southern hemisphere for southern winter and summer, resp. These findings also agree with the higher variance of background error for lows than for highs in the implicitly evolved covariances of the ECMWF 4D-Var system (Thépaut et al. 1996). Fig. 3: Same as fig.2, but for summer 2004. Correlations obtained from forecast differences of the horizontal wind at the same vertical level show a similar flow-dependence. Figure 4 compares the transverse wind correlations at 45°N for contributions of "high” and "low” pressure, as determined by the geopotential height of the 500 hPa surface. Again, the correlations are clearly broader in the former case. The flow-dependence of the correlations of longitudinal wind is significantly smaller, see fig. 5. Fig. 4: Flow-dependence of transverse wind correlations at 500 hPa, 45°N, winter 2003/2004. Fig. 2: Flow-dependence of the zonally averaged standard deviation of the 48h-24h forecast differences of the 500 hPa height for winter 2003/2004. Fig. 5: Same as fig.4, but for longitudinal wind. The same pattern is found in the crosscorrelation of geopotential height and transverse wind (fig. 6). This result is expected because of the geostrophic balance relationship that is well satisfied at mid- and high latitudes. It also stresses that a proper treatment of mass-wind balance is an essential ingredient in a flow-dependent modeling of background error covariance. the local minimum of the correlation length scale is shifted upwards because the tropopause level is higher during these periods. The flow-dependence of background error covariances manifests itself also in the empirical vertical correlations. Figure 8 shows the vertical temperature correlation with the 700 hPa surface for summer 2004. Again, the blue line represents the result from taking all contributions into account, while the green and red lines show the correlations for "highs" and "lows", respectively. Fig. 6: Flow-dependence of the cross-correlation of 500 hPa height and transverse wind. We extended the above analyses of the horizontal correlations also to other pressure levels. In order to keep a uniform criterion for the selection of meteorological situations, we always determined the flow by the geopotential height of the co-located 500 hPa surface. Horizontal correlation length scales were obtained from fits of the empirical correlations to a second order autoregressive function. The dependence of the horizontal correlation scale on vertical level is displayed in fig. 7. The data clearly demonstrate that there is a considerable variation of correlation scale with flow pattern also at other levels. Fig. 8: Flow-dependence of the vertical temperature correlation with 700 hPa, summer 2004. 4. Outlook Investigations are underway how to perform a consistent modeling of a symmetric and positive definite B-matrix that incorporates the empirical flow-dependence presented here. As an essential ingredient, the simple local selection criterion for the meteorological situation used here has to be extended to a bi-local and level-dependent formulation that automatically satisfies the symmetry and positive-definiteness constraints. References D. Majewski, D. Liermann, P. Prohl, B. Ritter, M. Buchhold, T. Hanisch, G. Paul, W. Wergen and J. Baumgardner, The operational global icosahedralhexagonal gridpoint model GME: Description and highresolution tests, Mon. Wea. Rev. 130, 319 (2002) D. F. Parrish and J. D. Derber, The National Meteorological Center’s Spectral Statistical-Interpolation Analysis System, Mon. Wea. Rev. 120, 1747 (1992) Fig. 7: Vertical profile of the length scale of the horizontal geopotential correlation as a function of the co-located 500 hPa height, 45°N, winter 2003/2004. Results for the summer seasons 2003 and 2004 were similar, although the vertical location of L. P. Riishøjgaard, A direct way of specifying flowdependent background error correlations for meteorological analysis systems, Tellus 50A, 42 (1998) J.-N. Thépaut, P. Courtier, G. Belaud and G. Lemaître, Dynamical structure functions in a four-dimensional variational assimilation: A case study, Q. J. R. Meteorol. Soc. 122, 535 (1996)