LANGUAGE TESTS FOR SOCIAL COHESION AND CITIZENSHIP :

advertisement

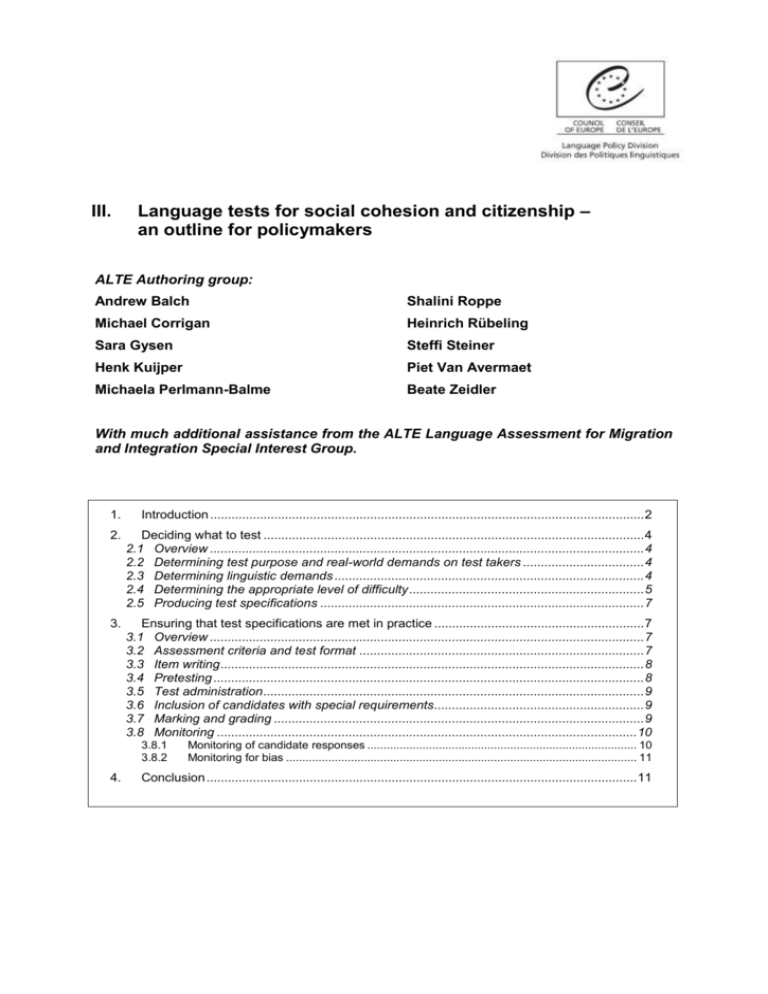

III. Language tests for social cohesion and citizenship – an outline for policymakers ALTE Authoring group: Andrew Balch Shalini Roppe Michael Corrigan Heinrich Rübeling Sara Gysen Steffi Steiner Henk Kuijper Piet Van Avermaet Michaela Perlmann-Balme Beate Zeidler With much additional assistance from the ALTE Language Assessment for Migration and Integration Special Interest Group. 1. Introduction .......................................................................................................................... 2 2. Deciding what to test ........................................................................................................... 4 2.1 Overview .......................................................................................................................... 4 2.2 Determining test purpose and real-world demands on test takers .................................. 4 2.3 Determining linguistic demands ....................................................................................... 4 2.4 Determining the appropriate level of difficulty .................................................................. 5 2.5 Producing test specifications ........................................................................................... 7 3. Ensuring that test specifications are met in practice ........................................................... 7 3.1 Overview .......................................................................................................................... 7 3.2 Assessment criteria and test format ................................................................................ 7 3.3 Item writing ....................................................................................................................... 8 3.4 Pretesting ......................................................................................................................... 8 3.5 Test administration ........................................................................................................... 9 3.6 Inclusion of candidates with special requirements........................................................... 9 3.7 Marking and grading ........................................................................................................ 9 3.8 Monitoring ...................................................................................................................... 10 3.8.1 3.8.2 4. Monitoring of candidate responses ................................................................................... 10 Monitoring for bias ............................................................................................................ 11 Conclusion ......................................................................................................................... 11 1. Introduction Many European countries are introducing or formalising linguistic requirements for the purposes of migration, residency and citizenship, and national governments often require language tests or other formal assessment procedures to be used. It is not the purpose of this chapter to promote the use of such language tests but, where mandatory testing is either in place or under consideration, to offer professional guidance based on good testing practice so as to ensure that the needs of stakeholders are met and that tests are fair for test takers. Test fairness is a particularly important quality when tests are related to migration, residency or citizenship. Unfair tests may result in migrants being denied civil or human rights. There are a number of easily-available standards (see further reading) which provide guidance for developing and administering fair tests. They may be read in conjunction with the remainder of this chapter for an illustration of how different elements of the testing process relate to an ethical framework. Where language assessment is being considered, policy makers are urged to first consider issues at a deeper level: is it more appropriate to use another form of assessment, rather than a test? could it be appropriate to use more than one method of assessment in combination? what use will be made of the test results? what will the consequences of a test on society be? what will the impact for the migrant be? what will the impact for the migrant’s society be? Mode of assessment When considering the first and second points, policy makers should be aware that there are other forms of assessment which may also be appropriate. Tests and other methods of assessment each have their own particular advantages, relating to characteristics such as impact on the candidate, the interpretability of results, standardisation and reliability of results, and cost and practicability. It is therefore important that the requirements of the situation are considered carefully to identify the most appropriate kind of assessment. It should also be noted that a combination of assessment methods is possible. Some of the advantages of tests and other forms of assessment are noted here: Tests which are properly designed, constructed and administered have the following advantages: results are highly standardised and reliable. This means that it is easy to compare candidates across the same or different administrations candidates are assessed with a high degree of independence and objectivity large numbers may be tested in a short space of time. Alternatives to tests might take the form of continuous assessment throughout a course, or the assessment of a range of miscellaneous evidence which the candidate is able to present1. If the assessment is intended to have a strong formative influence, it may be done as part of a course and help the learner to take a greater role in directing their learning. The assessment See Part I in this volume: “The Common European Framework of Reference for Languages and the development of policies for the integration of adult migrants”, David Little 1 2 itself may involve self-assessment as well as peer and group assessment. In addition to the formative potential of such assessment already mentioned, advantages of this approach include: material gathered for assessment may be collected under non-threatening conditions (e.g. a classroom) and this may improve its validity as evidence for a candidate’s true ability there is the potential for evidence to come from tasks which are very close to real world tasks, or actually come from the performance of real world tasks, such as those identified as particularly important for migrants and citizens there is a greater potential for candidate’s performance to be judged holistically, and therefore to focus on the underlying ability of a candidate to successfully complete tasks, placing less emphasis on testing isolated language elements Impact It should be noted that when dealing with the consequences of any test, all test results are predicated on there being a certain margin of error, as no assessment can be claimed to be completely free of error. The aim of this chapter is, therefore, to help minimise the possibility of negative consequences stemming from test use by, among other things, reducing the possibility of error, rather than aiming to remove it completely. Furthermore, large-scale tests cannot easily take into account the personality traits, learning history and personal history of an individual candidate when assessing ability. If the candidate has done unduly poorly in the test, their true ability will be underestimated. Therefore, the overall benefit which it is hoped will be attained by administering the test has to be considered in relation to the consequences of failure in the test, since some of the decisions based on test results may have been made on the basis of inaccurate information. When the mode of assessment has been selected, consideration of the use and consequences is very important as the use can have some very far reaching and unexpected consequences. It is advised that, in planning assessment, possible consequences are carefully considered and, during the operation of the assessment, research is done to discover what the actual consequences are. Possible consequences include changes in teaching and learning practices as a result of the test, or changes in the education system of the migrant’s country. After considering the issues presented above, if it is felt that a language test should be used, those involved, including the policy makers, need to be sure that (i) the test is developed to fulfil the need identified and that (ii) it functions as intended in order for the related policy to be applied appropriately and fairly. Test fairness is relevant to all types of language test and for all candidates, but, as mentioned above, it is especially important in the case of tests for migration, residency and citizenship, due to the serious implications for the test taker in terms of civil and human rights. The work of ensuring that a test is fair is something that will begin in the planning stages and must continue throughout the operation of the test. This work will allow test users to properly interpret and use the results of such a test. To assist policy makers with their responsibility in this respect, the remainder of this chapter will provide information on all stages of test development and operation and will therefore inform the selection and monitoring of a test provider and the interpretation of results, or act as a guidance for in-house production of tests. As with all tests, the result of the application of the good testing practice described in this chapter will help ensure that not only are appropriate skills and knowledge tested (making the test valid) but also that this is done consistently for all candidates and across all test versions (making the test reliable). References will also be made in this chapter to other resources which can provide further assistance with this work. 3 further reading: ALTE Code of Practice – http://www.alte.org/quality_assurance/index.php Multilingual Glossary of Language Testing Terms, Studies in Language Testing volume 6, Cambridge University Press (ISBN: 0-521-65877-2) ILTA Code of Ethics – http://www.iltaonline.com/code.pdf JCTP Code of Fair Testing Practice in Education – http://www.apa.org/science/FinalCode.pdf 2. Deciding what to test Overview In this section, the steps involved in ensuring that the design of the test fits its purpose are outlined. The first step in this process is the precise and unambiguous identification of the purpose of the test. After this is done, principled ways to determine the content and difficulty follow. Finally, the test specifications document, a document essential in later stages of test construction and review, must be developed. Determining test purpose and real-world demands on test takers Before developing any language test, it is first necessary for the precise purpose to be determined. It is not sufficient to state that a test is for the purposes of migration and citizenship, because even within this area, there is a wide range of reasons for testing migrants, ranging from motivating learners (to help them use and improve their current competence in the target language), ascertaining whether their competence is sufficient for participation in well-defined social situations (e.g. study or work), to making decisions which affect their legal rights, such as their right to remain in a country or acquire citizenship of it. Only when the purpose has been clearly defined is it possible to identify the real-world demands that test-takers will face (e.g. the need to take part in societal processes and exercise the rights and responsibilities of citizenship) and which should be reflected in the test. As well as informing test development, a clear and explicit purpose will not only help to clarify test takers’ expectations, contributing to test fairness, but will also allow other members of society to interpret and use test results appropriately. This process of establishing the needs is termed needs analysis. When conducting this needs analysis, it is also necessary to take into account the fact that there are various subgroups of migrants with their own specific needs. Those, for instance, who want to join the job market as soon as possible often have different needs from those who are planning to raise young children at home. In a needs analysis, it is good practice for language test developers to define the relevant contexts and situations of the target group. In planning such needs analyses, policy makers should be sure to set aside sufficient resources and delegates from different sections of society should be involved in the definition of the needs. Determining linguistic demands Once these real-world demands have been identified, they must be translated into linguistic requirements specifying not only the knowledge and skills, but also the ability level for each that the test-taker is likely to need. If, for instance, a language test were designed to gauge whether the test-taker had the language proficiency necessary to follow a vocational training course, we might expect it to test the ability to follow lessons and workshops, to communicate with teachers and fellow students, to read relevant literature, to write 4 assignments, etc. This analysis could then help to determine the appropriate level of language proficiency required (or the levels required in each of the individually tested skills such as reading and writing). If, on the other hand, a language test were designed for the certification of translators or interpreters, a comparable needs analysis of the profession would show the required level of proficiency to be much higher, and it would be found that for the translator, higher levels would be required in reading and writing proficiency, whilst for interpreters oral proficiency would be more important. In contrast to the examples above, deriving linguistic requirements from relevant real-world tasks is far less straightforward in the case of migrants and candidates for citizenship. The relation between language proficiency in the official language(s) and the ability to integrate into society and/or exercise the rights and responsibilities of citizenship is looser and far more difficult to pin down. After all, if language proficiency were the only factor in play, all native inhabitants of a country would be fully integrated citizens. As this is not the case, it can be deduced that other factors are also important. The task for the language test developer is, nevertheless, to identify the relevant linguistic demands that apply. After a careful needs analysis as described above, it is also important to ensure that mistaken assumptions about candidates’ cultural or educational background do not influence the test. Language tests for study and work are, in most cases, taken by groups of candidates which are homogeneous with respect to educational background and cognitive skills, whereas tests for integration and citizenship (tests to acquire civil rights) must cater for a full range of possible candidates, and must therefore be accessible to people with little or no literacy skills, as well as those with a high level of academic education. Determining the appropriate level of difficulty Once the linguistic demands have been identified, developers should attempt to map them onto the can do statements of the Common European Framework of Reference of Languages2 (CEFR). This framework provides a common basis for the elaboration of language syllabuses, curriculum guidelines, examinations, textbooks, etc. across Europe. It describes what language learners have to learn to do in order to use a language for communication and what knowledge and skills they have to develop so as to be able to act effectively. CEFR, p1 The framework contains a number of illustrative scales (one each for speaking, writing, reading, listening and interaction), defining levels of proficiency, showing what a learner can do at each level and allowing progress to be measured along a six–level scale, A1 (low proficiency) to C2 (high proficiency). 2 Council of Europe / Cambridge University Press, 2001. Available online: www.coe.int/lang 5 C2 C E F R l e v e l C1 typical progress of a learner over time B2 B1 position of a learner on the CEFR’s system of levels A2 A1 time → Figure 1 learning progress and the CEFR levels Figure 1 shows a typical learner’s progress over time against the CEFR levels represented as horizontal bands. It should be noted that the width of each level on this diagram should not be taken to imply that a similar length of time is required to reach each additional level. For this reason, the curve illustrating typical progress of a learner is steep near the beginning and flattens out towards the end. This is because the range of skills and language added at each level, and therefore the time required to move from one level to the next, increases as progress is made. The needs analysis should therefore not be based on the number of study hours but on the careful mapping of stakeholder needs onto can do statements. Test constructors should also be aware that the competences of most candidates are not evenly spread over the four skills: reading, listening, writing and speaking, as Figure 1 suggests. Rather, it is common that competences in speaking and listening are higher than in those involving writing and reading. The learner marked on the diagram, therefore, might have a jagged profile when the four language skills are considered, as illustrated Figure 2. Test providers may therefore find some benefit in explicitly profiling competencies through the assessment. C2 C1 B2 B1 A2 A1 reading listening speaking writing Figure 2 A learner’s jagged language ability profile Aside from giving a more accurate picture of a candidate’s abilities, a modular approach to testing has several advantages. If it is possible to sit a test for each skill separately, candidates can sit a test of those skills they are better at, which can be more motivating, rather than on all four skills at once. This option would be especially suitable for the group of illiterate migrants or for participants with very little experience in writing. A corollary of 6 this approach is that language courses can focus on those skills that need more attention. In communicating the results of a test of partial competencies to the public, testing institutions have to be very clear about the skills that have been tested so that there is no confusion between tests of partial competences and tests of all the four skills. Test reports or certificates from profiled tests should therefore not show one overall level of ability for a candidate but rather the level achieved in each skill. further reading: The Common European Framework of Reference for Languages: Learning, Teaching, Assessment – [www.coe.int/lang] http://www.coe.int/t/dg4/linguistic/CADRE_EN.asp Producing test specifications Once the target candidature, purpose and testing focus have been decided upon, these should be documented in detailed test specifications. Specifications also describe the item or task types to be used, the format of the test and other practical matters. The rationale for deciding such practical matters will also be derived from the basic precepts, such as target candidature. These specifications then act as a reference document, informing decisions at all later stages of test use. 3. Ensuring that test specifications are met in practice 3.1 Overview Once the test specifications have been finalised, several further stages are necessary if the test is to work as intended. Assessment criteria and a test format need to be developed, and test items (‘questions’) written in accordance with the specifications, proven to meet them and then assembled into appropriate test combinations according to the specifications. Once produced, the test needs to be administered consistently and fairly for the intended testtakers. Finally, the data resulting from the test administration should be analysed to confirm that the test performed as expected, and adjustments made where this is not the case. Throughout this process, quality assurance checks are needed and are described in the text. There are a number of useful documents which aim to assist test providers in implementing the codes of practice/ethics mentioned in the further reading section of the introduction to this chapter. They suggest a more detailed and concrete form for the concepts discussed in the documents mentioned in the introduction and are listed in the further reading section here. further reading: AERA/APA/NCME Standards for Educational and Psychological Testing – http://www.apa.org/science/standards.html ALTE COP QMS Checklists – http://www.alte.org/quality_assurance/code/checklist.php ALTE Minimum standards for establishing quality profiles in ALTE examinations – http://www.alte.org/quality_assurance/index.php ALTE Principles of Good Practice – http://www.alte.org/quality_assurance/code/good_practice.pdf EALTA Guidelines for Good Practice – http://www.ealta.eu.org/guidelines.htm ILTA Draft Code of Practice – http://www.iltaonline.com/ILTA-COP-ver3-21Jun2006.pdf 3.2 Assessment criteria and test format The testing focus as outlined in the test specifications (2.5) will need to be broken down into specific, individual testing points in order to be of use to the test developer. It is only then, when a clear picture has developed of how candidate performance will be assessed, that work can begin on developing a suitable combination of test tasks and task types. Foremost 7 in the developer’s mind should be the need to provide candidates with adequate opportunities to demonstrate that they meet the assessment criteria. 3.3 Item writing In order to write appropriate test items, item writers need to be given clear guidelines. These would normally provide an overview of the target candidature and the test’s purpose, along with general advice such as the suitability or unsuitability of certain topics, the length of the input (e.g. number of words in a reading text), and output (i.e. number of words candidates should write), the degree to which texts must be ‘authentic’, etc. before focussing on each item type in turn. Once items have been written, other experts should then judge whether both the letter and the spirit of the guidelines have been respected. further reading: Item Writer Guidelines - http://www.alte.org/projects/item_writer.php 3.4 Pretesting The use of expert judgement (in 3.3 above) should lead to items which appear suitable for testing purposes. However, in order to confirm that the items actually work as intended (testing the target language, differentiating effectively between stronger and weaker candidates, not resulting in bias towards a particular candidate profile, etc), it is necessary to pretest the materials under test conditions on candidates with as similar a demographic profile as possible to that of the live test candidature. Pretesting of objectively-marked (e.g. multiple-choice) tests culminates in a detailed statistical analysis, whereas that of subjectively-marked tests (e.g. speaking tests) is more likely to lead to the qualitative analysis of the candidates’ production to determine the extent that this met the test provider’s expectations. Based on these analyses, items and tasks can be either accepted for future live test use, edited and pretested again, or rejected. In addition, if an item bank is created and filled with items, each with slightly different characteristics, tests can then be constructed with certain desired characteristics, such as that of covering a precise range of ability levels. At various stages during item writing and pretesting, it is important for experts to review tasks and items. This should probably happen more than once, as items may be altered and will therefore need to be reviewed again, or new information can become available (i.e. the results of pretesting). Some tools to assist with such reviews are listed in the further reading section. Items and tasks and sometimes responses to the tasks can be analysed through the categories in these instruments and it can be established how tasks differ from each other and to what extent the task accords with the test specifications. The Grids mentioned below were originally designed to assist test providers in aligning their examinations to the CEFR but may be used with this slightly wider aim in mind. further reading: Content Analysis Checklists – http://www.alte.org/projects/content.php Council of Europe: www.coe.int/portfolio CEFR Grids for the analysis of test tasks (listening, reading, speaking and writing) [http://www.coe.int/T/DG4/Portfolio/?L=E&M=/documents_intro/Manual.html] See also: Illustrations of the European levels of language proficiency [http://www.coe.int/T/DG4/Portfolio/?L=E&M=/main_pages/illustrationse.html] 8 3.5 Test administration Test providers should ensure that the test is taken under conditions which are equally fair for all candidates. To this end, it is recommended that procedures be developed to minimise differences in administration. These procedures should ensure: test centres are suitably accredited for the overall administration of the tests test centre staff are professionally competent, adequately informed and supported, and monitored as necessary a high level of security and confidentiality is maintained at examination centres throughout the whole process from enrolment to issuing results and report papers at the end of the process physical conditions in the exam room are appropriate (level of noise, temperature, distance between candidates, etc). arrangements are made for test takers with special requirements 3.6 Inclusion of candidates with special requirements The testing system must not discriminate against candidates with special requirements. These may include temporary of long-term physical, mental or emotional impairments or disabilities, learning disorders, temporary or long-term illness, illiteracy in the L1 or target language, regulations related to religion, penal confinement or any other circumstances which would make it difficult or impossible for a candidate to take the test in the same way as anyone else. Provisions should exist to: decide whether any candidates with special requirements will be exempt from taking the test, or parts of the test take suitable measures in order to ensure that candidates with special requirements are judged fairly define which institution is responsible for deciding whether the test has to be taken by a particular candidate which special conditions apply in any given case (e.g. test papers in Braille, test papers in large print, provision of a Brailler or computer with special features, provision of a reader/scribe/assistant, extended time for certain parts of the test, additional rest breaks, sign language interpreter, special examination dates or venues) ensure that an appeal against this decision is possible, inform candidates how an appeal should be applied for and outline the way in which a final decision should be made Information on these regulations and exemptions should be publicly available and accessible to the candidates. further reading: "Special Educational Needs in Europe. The Teaching & Learning of Languages. Teaching Languages to Learners with Special Needs", European Commission, DG EAC 23 03 LOT 3, January 2005. 3.7 Marking and grading Objectively marked test items can be marked accurately by machines or by trained markers. Subjectively marked items usually need to be marked by trained raters. This procedure is more likely to lead to clerical and judgemental error. Judgemental error takes the form of 9 inconsistencies in examiners’ interpretation of candidate responses and/or application of the test’s assessment criteria. Examiners can be inconsistent either when compared with other examiners or in the way they themselves apply the criteria over time. Such inconsistencies can be greatly reduced through the application of rigorous training and monitoring procedures, as well as through the additional marking of some or all of the candidate performances by other raters. Markers’ work could also be ‘scaled’ to compensate for consistent leniency/harshness, though significant differences are likely to require further training. 3.8 Monitoring As well as monitoring the behaviour of examiners (3.7, above), it is also important that the language test developer collect and analyse both information about candidate responses and demographic information about the candidates (e.g. age, gender and nationality). This is necessary to ensure that: each test measures the abilities it sets out to the abilities are measured in a consistent way by all versions of the same test, past and future each test works in a way which is fair to all targeted test takers, no matter what their background The results of such monitoring can then be used to ensure that test results accurately portray the ability of the candidate. Additionally, conclusions from the analysis can be fed back into the test construction, administration and grading processes, so that these processes may be continually improved. 3.8.1 Monitoring of candidate responses During live tests, candidate responses to items and tasks are used both to provide raw scores and to give test providers information on how well the items and tasks performed in measuring candidate ability (see 3.4 above). Items should be gauged not only for their level of difficulty, but also on the extent to which they discriminate between stronger and weaker candidates (because the basic aim of the test is to distinguish between these two groups). A record of these and other statistics should be kept and comparison made between them for past and future versions of the test. This will allow test providers to ensure that results from one version or session of the test are comparable with those from another. Where test construction has been based on pretesting, it is likely that items and tasks would perform as expected in the live test. However, confirmation of this through analysis is important and investigation followed by corrective action may be needed where performance is not as expected. It is, of course, also important that a particular version of a test indicates the ability of candidates in a way which is consistent with past and future versions. For this reason, live response data is often used to help decide grade boundaries or pass marks. If a candidate were to take two different versions of the same test, they would be unlikely to achieve exactly the same raw score. However, it is possible for the test provider to ensure with reasonable certainty that the candidate would get the same grade, or fall the same side of the pass mark on both tests. This can be done by equating one test to the other, or judging which score in version B is equal to the score needed to pass version A. Where pretesting has been carried out, such judgement may be easier to make and is likely to be more accurate. 10 3.8.2 Monitoring for bias Similar techniques to those outlined in 3.8.1 above should also be applied to the performance of groups of candidates with the same ability levels. If, for example, compared to other candidates of the same ability, candidates of one nationality were found to do significantly better or worse on an item or group of items, this may be due to item bias towards or against people of that particular nationality and would therefore be unfair. However, the cause may also be linguistic differences/similarities between the native and target languages, which cannot be considered unfair. Either way, after quantitative investigation has exposes possible bias, qualitative investigation is needed. If an item is found to be biased, this may require its removal and/or changes in the procedures by which items are produced. 4. Conclusion Using tests for migration and citizenship purposes is considerably more complex than it may at first seem. This chapter has attempted to outline the issues that need to be considered and, by implication, the issues for which policy makers should take responsibility. The questions of what type of assessment is necessary for the intended purpose, and what it can be expected to measure should be considered first. Where it has been decided to use a test, it is vital that the test meets the requirements outlined in this chapter. The test should be continually monitored to ensure its functioning and quality. It must not be forgotten, also, that the outcomes of a test can have important consequences both for the candidates, for larger groups of people, and the society as a whole. Among these consequences are those relating to the civil and human rights of the test taker. For the successful use of a language test for migration and citizenship purposes, those who define the policy must work with the test providers on several aspects after the decision to use a test has been made. These aspects include the definition of the precise purpose of the test and the allocation of resources for successful completion of all stages of test development and test use. At all times, test fairness should be considered of prime importance. 11