Piriformis Syndrome

advertisement

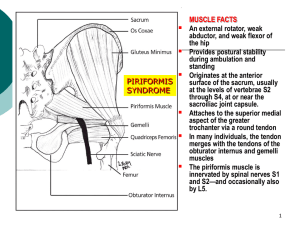

Piriformis Syndrome Rate this Article Email to a Colleague Last Updated: March 16, 2006 Get CME/CE for article Synonyms and related keywords: hip socket neuropathy, pseudosciatica, wallet sciatica, deep gluteal syndrome, pyriformis syndrome AUTHOR INFORMATION Section 1 of 10 Author Information Introduction Clinical Differentials Workup Treatment Follow-up Miscellaneous Pictures Bibliography Author: Milton J Klein, DO, Consulting Staff, Department of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, Sewickley Valley Hospital and Ohio Valley General Hospital Milton J Klein, DO, is a member of the following medical societies: American Academy of Disability Evaluating Physicians, American Academy of Osteopathy, American Academy of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, American Association of Neuromuscular and Electrodiagnostic Medicine, American Medical Association, American Osteopathic Association, and American Osteopathic College of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation Editor(s): Rajesh R Yadav, MD, Assistant Professor, Section of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, MD Anderson Cancer Center, University of Texas at Houston; Francisco Talavera, PharmD, PhD, Senior Pharmacy Editor, eMedicine; Michael T Andary, MD, MS, Residency Program Director, Associate Professor, Department of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, Michigan State University College of Osteopathic Medicine; Kelly L Allen, MD, Consulting Staff, Department of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, Lourdes Regional Rehabilitation Center, Our Lady of Lourdes Medical Center; and Consuelo T Lorenzo, MD, Consulting Staff, Department of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, Alegent Health Care, Immanuel Rehabilitation Center Disclosure Quick Find Author Information Introduction Clinical Differentials Workup Treatment Follow-up Miscellaneous Pictures Bibliography Click for related images. Related Articles [Lumbar Degenerative Disc Disease] Lumbar Facet Arthropathy Lumbar Spondylolysis and Spondylolisthesis Myofascial Pain Trochanteric Bursitis INTRODUCTION Section 2 of 10 Author Information Introduction Clinical Differentials Workup Treatment Follow-up Miscellaneous Pictures Bibliography Background: Piriformis syndrome has remained a controversial diagnosis since its initial description in 1928. Piriformis syndrome usually is caused by a neuritis of the proximal sciatic nerve. The piriformis muscle can either irritate or compress the proximal sciatic nerve due to spasm and/or contracture, and this problem can mimic a diskogenic sciatica (pseudosciatica). Pathophysiology: The piriformis muscle is flat, pyramid-shaped, and oblique. This muscle originates to the anterior of the S2-S4 vertebrae, the sacrotuberous ligament, and the upper margin of the greater sciatic foramen (see Image 1). This muscle passes through the greater sciatic notch and inserts on the superior surface of the greater trochanter of the femur. With the hip extended, the piriformis muscle is the primary external rotator; however, with the hip flexed, the piriformis muscle itself becomes a hip abductor. This muscle is innervated by branches from L5, S1, and S2. A lower lumbar radiculopathy also may cause secondary irritation of the piriformis muscle, which may complicate the diagnosis and hinder patient progress. Many developmental variations of the relationship between the sciatic nerve in the pelvis and piriformis muscle have been observed. In approximately 20% of the population, the muscle belly is split with one or more parts of the sciatica nerve dividing the muscle belly itself. In 10% of the population, the tibial/peroneal divisions are not enclosed in a common sheath. Usually, the peroneal Continuing Education CME available for this topic. Click here to take this CME. Patient Education Click here for patient education. portion splits the piriformis muscle belly; the tibial division rarely splits the muscle belly. Involvement of the superior gluteal nerve usually is not seen in cases of piriformis syndrome. This nerve leaves the sciatic nerve trunk and passes through the canal above the piriformis muscle. Blunt injury may cause hematoma formation and subsequent scarring between the sciatic nerve and short external rotators. Nerve injury can occur with prolonged pressure on the nerve or vasa nervorum. Etiology can be subdivided into a few categories as follows: Hyperlordosis Muscle anomalies with hypertrophy Fibrosis (due to trauma) Partial or total nerve anatomical abnormalities Other causes can include the following: Pseudoaneurysms of the inferior gluteal artery adjacent to the piriformis syndrome Bilateral piriformis syndrome due to prolonged sitting during an extended neurosurgical procedure Cerebral palsy Total hip arthroplasty Myositis ossificans Vigorous physical activity This syndrome remains controversial because, in most cases, the diagnosis is clinical, and no confirmatory tests exist to support the clinical findings. Papadopoulos et al proposed a new classification of piriformis syndrome. Primary piriformis syndrome is for all intrinsic pathology of the piriformis muscle itself, such as myofascial pain, anatomic variations, and myositis ossificans. Secondary piriformis syndrome (pelvic outlet syndrome) includes all other etiologies of piriformis syndrome, with the exclusion of lumbar spinal pathology. Frequency: In the US: Given the lack of agreement on exactly how to diagnose this condition, estimates of frequency of sciatica caused by piriformis syndrome vary from rare to approximately 6% of sciatica cases seen in a general family practice. Approximately 90% of adults have had at least one episode of disabling low back pain (LBP) in their lifetime. Mortality/Morbidity: Piriformis syndrome is not life-threatening, but it can have significant associated morbidity. The total cost of LBP and sciatica is significant, exceeding $16 billion in both direct and indirect costs. Sex: Some reports suggest a 6:1 female-to-male predominance. CLINICAL Section 3 of 10 Author Information Introduction Clinical Differentials Workup Treatment Follow-up Miscellaneous Pictures Bibliography History: Piriformis syndrome often is not recognized as a cause of LBP and associated sciatica. This clinical syndrome is due to a compression of the sciatic nerve by the piriformis muscle. This condition is identical in clinical presentation to LBP with associated L5, S1 radiculopathy due to diskogenic and/or lower lumbar facet arthropathy with foraminal narrowing. Not uncommonly, patients demonstrate both of these clinical entities simultaneously. This diagnostic dilemma highlights the need for patients with LBP and associated radicular pain to undergo a complete history and physical examination, including a digital rectal examination. Many cases of refractory trochanteric bursitis are observed to have an underlying occult piriformis syndrome due to the insertion of the piriformis muscle on the greater trochanter of the hip. If both the trochanteric bursitis and the piriformis syndrome are treated inadequately, both conditions remain resistant to medical management. Physical: Examination findings may include the following: Piriformis muscle spasm often is detected by careful deep palpation. Digital rectal examination may reveal tenderness on lateral pelvic wall that reproduces symptoms. Reproduction of sciatica type pain with weakness is noted by resisted abduction/external rotation (Pace test). The Freiberg test is another diagnostic sign that elicits pain upon forced internal rotation of the extended thigh. The Beatty maneuver reproduces buttock pain by selectively contracting the piriformis muscle. The patient lies on the uninvolved side and abducts the involved thigh upward; this activates the ipsilateral piriformis muscle, which is both a hip external rotator and abductor with the hip flexed. A painful point may be present at the lateral margin of the sacrum. Shortening of the involved lower extremity may be seen. The patient may have difficulty sitting due to an intolerance of weight bearing on the buttock. The patient may have the tendency to demonstrate a splayed foot on the involved side when in the supine position. Piriformis syndrome alone is rarely a cause of a focal neuromuscular impairment; either a sciatic mononeuropathy or an L5-S1 radiculopathy can mimic both of these conditions, obscuring diagnosis of piriformis syndrome. A Morton foot may predispose the patient to developing piriformis syndrome. The prominent second metatarsal head destabilizes the foot during the push-off phase of the gait cycle, causing foot pronation and internal rotation of the lower limb. The piriformis muscle (external hip rotator) reactively contracts repetitively during each push-off phase of the gait cycle as a compensatory mechanism, leading to piriformis syndrome. Causes: Approximately 50% of patients with piriformis syndrome have a history of trauma, with either a direct buttock contusion or hip/lower back torsional injury. The remaining 50% of cases are of spontaneous onset, so the treating physician must have a high index of suspicion for this problem, lest it be overlooked. DIFFERENTIALS Section 4 of 10 Author Information Introduction Clinical Differentials Workup Treatment Follow-up Miscellaneous Pictures Bibliography [Lumbar Degenerative Disc Disease] Lumbar Facet Arthropathy Lumbar Spondylolysis and Spondylolisthesis Myofascial Pain Trochanteric Bursitis Other Problems to be Considered: Lumbosacral radiculopathy Buttock pain Ischial tuberosity bursitis Sciatica WORKUP Section 5 of 10 Author Information Introduction Clinical Differentials Workup Treatment Follow-up Miscellaneous Pictures Bibliography Lab Studies: Laboratory studies generally are not indicated in diagnosing piriformis syndrome. Imaging Studies: Diagnostic imaging of the lumbar spine is mandatory to exclude associated diskogenic and/or osteoarthritic contributing pathology. Reports in the literature on piriformis muscle describe imaging by nuclear diagnostic studies and MRI of the pelvis, but these tests are neither practical nor reliable diagnostic approaches to this problem. The history and clinical diagnostic examination provide the greatest and most specific diagnostic yield for this problem. Diagnostic ultrasound imaging of the piriformis muscle for assessment of muscle morphology has demonstrated a significant correlation of piriformis muscle morphology abnormality, especially in patients with lumbosacral/buttock pain and pain ascending stairs, referred pain to the posterior thigh on the symptomatic side, and reproduction of pain with needling of the piriformis muscle. Other Tests: Results of electrodiagnostic testing for piriformis syndrome usually are normal. Reports of positional H-reflex abnormalities can be found in the literature; however, such findings have not been widely accepted or reproduced. TREATMENT Section 6 of 10 Author Information Introduction Clinical Differentials Workup Treatment Follow-up Miscellaneous Pictures Bibliography Rehabilitation Program: Physical Therapy: Because a definitive method to accurately diagnose this problem is not available, treatment regimens are controversial and have not been subjected to randomized blind clinical trials. Despite this fact, numerous treatment strategies exist for patients with piriformis syndrome. Functional biomechanical deficits may include the following: o o o o o Tight piriformis muscle Tight hip external rotators and adductors Hip abductor weakness Lower lumbar spine dysfunction Sacroiliac joint hypomobility Functional adaptations to these deficits include the following: o o o Ambulation with thigh in external rotation Functional limb length shortening Shortened stride length Once the diagnosis has been made, these underlying perpetuating biomechanical factors must be corrected. Consider the use of ultrasound and other heat modalities prior to physical therapy sessions. Prior to performing piriformis stretches, the hip joint capsule should be mobilized anteriorly and posteriorly to allow for more effective stretching. Soft tissue therapies of the piriformis muscle can be helpful, including longitudinal gliding with passive internal hip rotation, as well as transverse gliding and sustained longitudinal release with the patient lying on his/her side. Addressing sacroiliac joint and low back dysfunction also is important. A home stretching program should be provided to the patient. These stretches are an essential component of the treatment program. During the acute phase of treatment, stretching every 2-3 hours (while awake) is a key to the success of nonoperative treatment. Prolonged stretching of the piriformis muscle is accomplished in either a supine or orthostatic position with the involved hip flexed and passively adducted/internally rotated. Medical Issues/Complications: No consensus exists on overall treatment of piriformis syndrome due to lack of objective clinical trials. Conservative treatment (eg, stretching, manual techniques, injections, activity modifications, modalities like heat or ultrasound, natural healing) is successful in most cases. Injection therapy can be incorporated if the situation is refractory to the aforementioned treatment program. For effective injection, the piriformis muscle must be localized manually by digital rectal examination. Then the piriformis muscle is injected using a 3.5-inch (8.9-cm) spinal needle. Care must be taken to avoid direct injection of the sciatic nerve. Surgical Intervention: Surgical management is the treatment of last resort. Surgery for this condition involves resection of the muscle itself or the muscle tendon near its insertion at the superior aspect of the greater trochanter of the femur (as described by Mizuguchi). These surgical procedures are described as effective, and they do not cause any associated superimposed postoperative disability. Consultations: Because of the enigmatic nature of piriformis syndrome, initial consultation obtained from an orthopedic surgeon or similar specialist usually is nonspecific. This disorder is considered to be a soft tissue problem that presents as low back or buttock pain with sciatica. After all differential diagnoses have been excluded, consider piriformis syndrome. Due to the traumatic etiology of most cases, piriformis syndrome usually is associated with other more proximal causes of LBP, sciatica, and buttock pain (thereby further clouding the diagnosis). Other Treatment (injection, manipulation, etc.): The Spray N' Stretch myofascial treatment and ultrasound modality preceding physical therapy sessions are useful. Manual muscle medicine, including facilitated positional release, may be helpful. Injections with steroids, local anesthetics, and botulinum toxin type B (12,500 U) have been reported in the literature for management of this condition. No single technique is universally accepted. Localization techniques include manual localization of muscle with fluoroscopic and electromyographic guidance. The piriformis muscle, after localization with a digital rectal examination, can be injected with a 3.5-inch (8.9-cm) spinal needle. Care should be taken to avoid direct injection of the sciatic nerve. FOLLOW-UP Section 7 of 10 Author Information Introduction Clinical Differentials Workup Treatment Follow-up Miscellaneous Pictures Bibliography Further Inpatient Care: Inpatient care would be necessary only if surgical intervention is warranted. Surgery is the last resort treatment for severe cases of piriformis syndrome. Further Outpatient Care: Piriformis syndrome usually is treated effectively with conservative measures. Please refer to the Treatment section for a discussion of treatment recommendations. Deterrence/Prevention: No method has been demonstrated to prevent piriformis syndrome. The best prevention is to maintain biomechanical balance by restoration of a more physiologic weight bearing distribution with a level pelvis/sacral base and equal leg lengths, achieved by heel lift therapy if necessary. This treatment approach also prevents recurrences of piriformis syndrome, especially if the underlying etiology is a leg-length discrepancy. The patient also must engage in a general stretching program that includes bilateral piriformis muscles. Complications: The most significant complication is failure to recognize, diagnose, and treat this disabling condition. If left untreated, a patient may undergo unsuccessful back surgery for a disk herniation; however, a coexisting occult piriformis syndrome can result in a failed back syndrome. Another complication is inadvertent direct injection of the sciatic nerve, which usually results in a nondisabling and temporary sciatic mononeuropathy. Prognosis: The prognosis depends upon early recognition and treatment. As this is a soft tissue syndrome, it has a tendency to be chronic, usually due to late diagnosis and treatment and has a less favorable prognosis. Patient Education: For conservative measures to be effective, the patient must be educated with an aggressive home-based stretching program to maintain piriformis muscle flexibility. He or she must comply with the program even beyond the point of discontinuation of formal medical treatment. MISCELLANEOUS Section 8 of 10 Author Information Introduction Clinical Differentials Workup Treatment Follow-up Miscellaneous Pictures Bibliography Medical/Legal Pitfalls: The greatest medical/legal concern is either misdiagnosis or failure to diagnose piriformis syndrome. In most cases, the diagnosis is one of exclusion. Therefore, if piriformis syndrome is not in the differential diagnosis list, it may be overlooked. The patient becomes a chronic pain patient doomed to a lifetime of disability and chronic management with medication. Because the diagnosis usually is elusive, missing the diagnosis does not constitute malicious negligence and, therefore, rarely would be sufficient grounds alone for a medical malpractice lawsuit. Piriformis syndrome may be a secondary perpetuating factor underlying chronic posttraumatic intractable LBP. Negligent misdiagnosis or delayed diagnosis of this condition has caused a significant degree of unnecessary disability and financial loss. Special Concerns: In female patients, piriformis syndrome may be a cause of dyspareunia, but, again, this connection becomes impossible to prove. Diagnosis of piriformis syndrome requires a high index of suspicion by either the primary care physician or the obstetric/gynecologic specialist/surgeon. A bimanual simultaneous vaginal-rectal examination of female patients to determine this soft tissue diagnosis helps the physician to prescribe appropriate treatment. Although it is a misdiagnosed etiology of LBP/sciatica, piriformis syndrome can be a significant cause of soft tissue pain and disability. This problem requires a skillful, attentive physician to conduct a thorough history/physical examination that provides an accurate diagnosis. Once the clinical diagnosis has been made, a specific treatment can be formulated to provide the best outcome with a minimal degree of long-term disability. PICTURES Section 9 of 10 Author Information Introduction Clinical Differentials Workup Treatment Follow-up Miscellaneous Pictures Bibliography Caption: Picture 1. Nerve irritation in the herniated disk occurs at the root (sciatic radiculitis). In the piriformis syndrome, the irritation extends to the full thickness of the nerve (sciatic neuritis). View Full Size Image eMedicine Zoom View (Interactive!) Picture Type: Image BIBLIOGRAPHY Section 10 of 10 Author Information Introduction Clinical Differentials Workup Treatment Follow-up Miscellaneous Pictures Bibliography Barton PM: Piriformis syndrome: a rational approach to management. Pain 1991 Dec; 47(3): 345-52[Medline]. Beatty RA: The piriformis muscle syndrome: a simple diagnostic maneuver. Neurosurgery 1994; 34: 512514[Medline]. Beauchesne RP, Schutzer SF: Myositis ossificans of the piriformis muscle: an unusual cause of piriformis syndrome. A case report. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1997 Jun; 79(6): 906-10[Medline]. Broadhurst NA, Simmons DN, Bond MJ: Piriformis syndrome: Correlation of muscle morphology with symptoms and signs. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2004 Dec; 85(12): 2036-9[Medline]. Brown JA, Braun MA, Namey TC: Pyriformis syndrome in a 10-year-old boy as a complication of operation with the patient in the sitting position. Neurosurgery 1988 Jul; 23(1): 117-9[Medline]. Durrani Z, Winnie AP: Piriformis muscle syndrome: an underdiagnosed cause of sciatica. J Pain Symptom Manage 1991 Aug; 6(6): 374-9[Medline]. Fishman LM, Zybert PA: Electrophysiologic evidence of piriformis syndrome. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 1992 Apr; 73(4): 359-64[Medline]. Fishman LM, Konnoth C, Rozner B: Botulinum neurotoxin type B and physical therapy in the treatment of piriformis syndrome: a dose-finding study. Am J Phys Med Rehabil 2004 Jan; 83(1): 42-50; quiz 51-3[Medline]. Freidberg AH: Sciatic pain and its relief by operation on muscle and fascia. Arch Surg 1937; 34: 337-49. Frymoyer JW: Back pain and sciatica. N Engl J Med 1988 Feb 4; 318(5): 291-300[Medline]. Jankiewicz JJ, Hennrikus WL, Houkom JA: The appearance of the piriformis muscle syndrome in computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging. A case report and review of the literature. Clin Orthop 1991 Jan; (262): 205-9[Medline]. Karl RD Jr, Yedinak MA, Hartshorne MF, et al: Scintigraphic appearance of the piriformis muscle syndrome. Clin Nucl Med 1985 May; 10(5): 361-3[Medline]. Lang AM: Botulinum toxin type B in piriformis syndrome. Am J Phys Med Rehabil 2004 Mar; 83(3): 198202[Medline]. Mizuguchi T: Division of the pyriformis muscle for the treatment of sciatica. Postlaminectomy syndrome and osteoarthritis of the spine. Arch Surg 1976 Jun; 111(6): 719-22[Medline]. Noftal F: The Piriformis Syndrome. Can J Surg 1988 Jul; 31(4): 210[Medline]. Pace JB, Nagle D: Piriform syndrome. West J Med 1976 Jun; 124(6): 435-9[Medline]. Papadopoulos EC, Khan SN: Piriformis syndrome and low back pain: a new classification and review of the literature. Orthop Clin North Am 2004 Jan; 35(1): 65-71[Medline]. Papadopoulos SM, McGillicuddy JE, Albers JW: Unusual cause of "piriformis muscle syndrome". Arch Neurol 1990 Oct; 47(10): 1144-6[Medline]. Parziale JR, Hudgins TH, Fishman LM: The piriformis syndrome. Am J Orthop 1996 Dec; 25(12): 81923[Medline]. Rask MR: Superior gluteal nerve entrapment syndrome. Muscle Nerve 1980 Jul-Aug; 3(4): 304-7[Medline]. Retzlaff EW, Berry AH, Haight AS, et al: The piriformis muscle syndrome. J Am Osteopath Assoc 1974 Jun; 73(10): 799-807[Medline]. Robinson D: Piriformis syndrome in relation to sciatic pain. Am J Surg 1947; 73: 355-8. Schiowitz S: Facilitated positional release. J Am Osteopath Assoc 1990 Feb; 90(2): 145-6, 151-5[Medline]. Steiner C, Staubs C, Ganon M, Buhlinger C: Piriformis syndrome: pathogenesis, diagnosis, and treatment. J Am Osteopath Assoc 1987 Apr; 87(4): 318-23[Medline]. TePoorten BA: The piriformis muscle. J Am Osteopath Assoc 1969 Oct; 69(2): 150-60[Medline]. Thiele GH: Tonic spasm of the levator ani, coccygeus and piriformis muscles. Trans Am Proct Soc 1936; 37: 14555. Uchio Y, Nishikawa U, Ochi M, et al: Bilateral piriformis syndrome after total hip arthroplasty. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg 1998; 117(3): 177-9[Medline]. Yeoman W: The relation of arthritis of the sacroiliac joint to sciatica. Lancet 1928; ii: 1119-22.