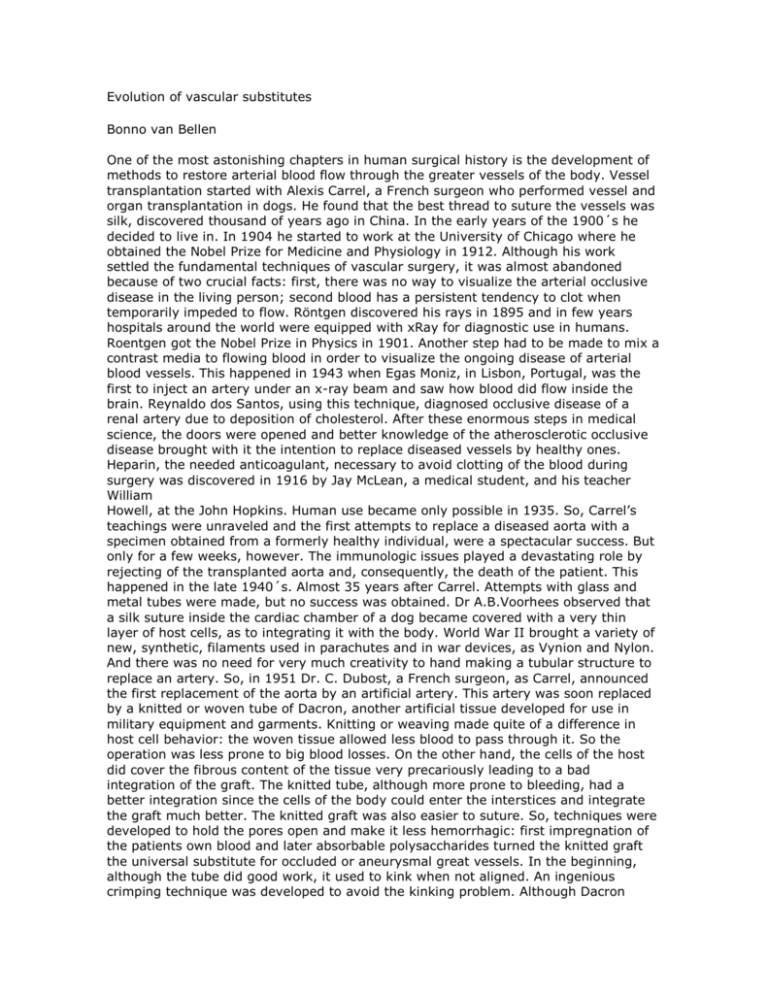

Evolution of vascular substitutes

advertisement

Evolution of vascular substitutes Bonno van Bellen One of the most astonishing chapters in human surgical history is the development of methods to restore arterial blood flow through the greater vessels of the body. Vessel transplantation started with Alexis Carrel, a French surgeon who performed vessel and organ transplantation in dogs. He found that the best thread to suture the vessels was silk, discovered thousand of years ago in China. In the early years of the 1900´s he decided to live in. In 1904 he started to work at the University of Chicago where he obtained the Nobel Prize for Medicine and Physiology in 1912. Although his work settled the fundamental techniques of vascular surgery, it was almost abandoned because of two crucial facts: first, there was no way to visualize the arterial occlusive disease in the living person; second blood has a persistent tendency to clot when temporarily impeded to flow. Röntgen discovered his rays in 1895 and in few years hospitals around the world were equipped with xRay for diagnostic use in humans. Roentgen got the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1901. Another step had to be made to mix a contrast media to flowing blood in order to visualize the ongoing disease of arterial blood vessels. This happened in 1943 when Egas Moniz, in Lisbon, Portugal, was the first to inject an artery under an x-ray beam and saw how blood did flow inside the brain. Reynaldo dos Santos, using this technique, diagnosed occlusive disease of a renal artery due to deposition of cholesterol. After these enormous steps in medical science, the doors were opened and better knowledge of the atherosclerotic occlusive disease brought with it the intention to replace diseased vessels by healthy ones. Heparin, the needed anticoagulant, necessary to avoid clotting of the blood during surgery was discovered in 1916 by Jay McLean, a medical student, and his teacher William Howell, at the John Hopkins. Human use became only possible in 1935. So, Carrel’s teachings were unraveled and the first attempts to replace a diseased aorta with a specimen obtained from a formerly healthy individual, were a spectacular success. But only for a few weeks, however. The immunologic issues played a devastating role by rejecting of the transplanted aorta and, consequently, the death of the patient. This happened in the late 1940´s. Almost 35 years after Carrel. Attempts with glass and metal tubes were made, but no success was obtained. Dr A.B.Voorhees observed that a silk suture inside the cardiac chamber of a dog became covered with a very thin layer of host cells, as to integrating it with the body. World War II brought a variety of new, synthetic, filaments used in parachutes and in war devices, as Vynion and Nylon. And there was no need for very much creativity to hand making a tubular structure to replace an artery. So, in 1951 Dr. C. Dubost, a French surgeon, as Carrel, announced the first replacement of the aorta by an artificial artery. This artery was soon replaced by a knitted or woven tube of Dacron, another artificial tissue developed for use in military equipment and garments. Knitting or weaving made quite of a difference in host cell behavior: the woven tissue allowed less blood to pass through it. So the operation was less prone to big blood losses. On the other hand, the cells of the host did cover the fibrous content of the tissue very precariously leading to a bad integration of the graft. The knitted tube, although more prone to bleeding, had a better integration since the cells of the body could enter the interstices and integrate the graft much better. The knitted graft was also easier to suture. So, techniques were developed to hold the pores open and make it less hemorrhagic: first impregnation of the patients own blood and later absorbable polysaccharides turned the knitted graft the universal substitute for occluded or aneurysmal great vessels. In the beginning, although the tube did good work, it used to kink when not aligned. An ingenious crimping technique was developed to avoid the kinking problem. Although Dacron tubes behaved very well as a substitute for the aorta and iliac arteries, they used to clot down when used to by-pass an obstructed femoral artery. Mr Gore invented an expanded form of politetrafluorethilene. This is a superb isolative garment for extreme temperatures and can be used as garments or as isolating tissue for tents. It is very often used in the army and for polar expedition. Dr. C.D. Campbell took advantage of its microporous structure, made a small tube of it and used it as a vascular substitute in smaller arteries, publishing his first results in 1976. All these technological advances in arterial grafting were put together with nitinol or steel to develop the intra-arterial grafts amenable to be delivered in a diseased artery to treat aneurismal disease by intravascular procedures, a procedure developed by Juan Parodi in 1990. Four thousend years and least three Nobel Prizes participated in the development of arterial substitutes, as a demonstration that nothing goes by itself and depends on the intersection of human mental power !