TB or not TB - IeDEA Southern Africa

advertisement

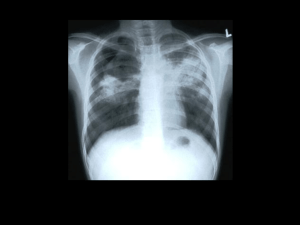

The ART-LINC collaboration Incidence of tuberculosis in antiretroviral treatment programs in lower-income countries: Impact of screening and diagnostic capacity. Draft 1.0 Target: Clinical Infectious Diseases Brief Report (1500 words max) We examined screening, diagnostic and treatment practices regarding TB in 24 ART programs from lower income countries. In suspected TB, chest X-ray (CXR), sputum examination and culture were available free of charge to patients in 21 (87.5%), 22 (91.7%) and 16 (66.7%) sites, respectively. Treatment was rifampin based at all sites, 4 (18.7%) used directly observed therapy (DOT) during the first 2 months and 6 (25%) during the entire treatment period. INH prophylaxis was routinely used in 6 sites (25%). The TB rate was 8.2 per 100 pyrs (95% CI 7.7 to 8.7) during the first year of ART. It was 12.4 in programs routinely screening for TB compared to 4.8 per 100 pyrs in programs not screening (adjusted rate ratio 0.39, 95% CI 0.20-0.79). Low baseline CD4 count were strongly associated (p<0.001) with a higher risk of TB in sites with access to chest X-rays (CXR), sputum and culture, but not in sites with more limited diagnostic capabilities. Only a minority of sites participating in this network routinely screen for TB before and during ART, and only half of programs use DOT. More intensive screening for TB may substantially improve case detection and might contribute to reducing the high early mortality observed in patients starting ART in low income countries. Introduction Although HAART reduces death rates remarkably from all causes, the management of tuberculosis (TB) and other opportunistic infections (OIs) remains an essential component of comprehensive HIV care. Nowadays, TB continues to cause morbidity and mortality in HIV-infected individuals since some HAART patients do not have a sustained response to antiretroviral agents for multiple reasons such as poor adherence, drug toxicities, drug interactions and initial acquisition of a drug-resistant strain of HIV1. Furthermore, the Starting Antiretrovirals at three Points in Tuberculosis (SAPIT) trial revealed that mortality among TB-HIV co-infected patients is reduced substantially if ART is provided with TB treatment 2 (what is the best ref?). An optimal scaling-up of antiretroviral therapy thus cannot be performed without a successful management of TB, including extended access to secondary prophylaxis, early diagnosis and affordable treatments. Despite this, the optimal use of existing diagnostic tests is failing nowadays3, resulting in missed diagnosis. Since standard Rifanpicin-based treatments have acceptable cure rates, high mortality rates in patients with both HIV and TB have been attributed those missed diagnosis4. Furthermore, HIV infection, negative sputum smear, extrapulmonary TB (two TB presentations being common in HIV infection) have been identified as main factors associated with diagnostic delay5. Thus, intensified case finding and appropriate diagnostic tools are nowadays key for trying to prevent TB fatalities. We examined screening, diagnostic and treatment practices regarding TB in ART programs in lower income countries. We additionally assessed the impact of screening and diagnostic practices on TB detection rate. Material and methods A cross-sectional survey was performed (December 2007 - April 2008) using an online questionnaire written in English, translated to French and revised after pilot testing. ARTLINC treatment programs were invited to complete the questionnaire, which comprehensively covered sites’ general practices regarding ART supply and HIV/AIDS management, including TB screening, diagnosis, prevention and treatment. The webbased WHO Data Collector system6 was used. All ART-LINC sites (n=24) agreed to participate to the survey and completed this web-based questionnaire. For 15 programs routinely recording detected TB cases, the site-level information could be linked to patient data prospectively collected after the start of ART (Botswana [Gaborone], Brazil [Porto Alegre and Rio de Janeiro], Côte d’Ivoire [Abidjan], India [Chennai], Kenya [Eldoret], Nigeria [Lagos], Malawi [Lilongwe], Morocco [Casablanca], Senegal [Dakar], South Africa [Cape Town, Khayelitsha, and Soweto], Thailand [Bangkok], and Uganda [Kampala]). Patients aged ≥16 years with a known date of HAART start, a documented baseline CD4 cell count and who had not previously received antiretroviral therapy were eligible. HAART was defined as any antiretroviral combination therapy that included ≥ 3 drugs. As of a previously published study7, the end point was a new pulmonary or extrapulmonary TB after HAART initiation, defined as a diagnosis of a TB episode at least 6 months after the last TB episode8. Time was measured from the start of HAART and ended at whichever of the following events occurred first: new TB event or death, last follow-up visit, or month 12 after HAART onset. Incidence rates were calculated for the first year of HAART (ref # 6 again). Crude TB incidences and adjusted rate ratios for baseline CD4, age and sex were computed according to the following sites characteristics: tuberculosis clinic as point of entry in the facility; TB diagnostic tests (CXR, sputum smear and cultures) availability and costs charged to patients or not; and routine TB CXR screening. To estimate the adjusted relative rates of 1-year tuberculosis incidence, we applied Poisson regression analyses with gamma-distributed random effects (xtpoisson procedure in Stata 10.0, Stata Corp, College Station, TX). Two additional random effects models were performed for a) sites performing routine active case identification through CXR screening and with full free diagnostic capacities (free CXR, sputum and culture for M. tuberculosis) (n=6) and b) sites without routine active case identification and partial diagnostic capacities (charges applicable to CXR and/or sputum; cultures not available or available with charges) (n=9). In those two models, the following patients-level variables were considered (baseline CD4 cell count and TB prophylaxis). Sites-specific variables included baseline population TB incidence9 and TB programme as important point of entry in HAART clinics. Both models were adjusted for age, sex and first-line antiretroviral regimen. Matthias: I think it would be better to adjust models from table 1 and 2 with the same covariates. It does not change anything anyway…. Results Seven of 24 sites (29.2%) routinely did CXR to screen for TB before and during ART. In suspected TB, CXR, sputum examination and culture were available free of charge to patients in 21 (87.5%), 22 (91.7%) and 16 (66.7%) sites, respectively. All sites routinely performing TB screening diagnosed TB cases using free CXR, sputum and cultures. In those not routinely performing screening, 76% did free CXR, 90% free sputum and 40% free cultures. Treatment was rifampin based at all sites, 10 (41.6%) used directly observed therapy (DOT) at least during the first 2 months or during the entire treatment period. INH prophylaxis was routinely used in 6 sites (25.0%) only. Eligible patients (n=19413) were included from the 15 sites routinely collecting data on TB. The median year of HAART onset was 2005 (IQR 2004-2005). The median CD4 cell count was 115 cells/µL (IQR 46-191). In the first year of HAART, 1081 tuberculosis events were diagnosed during 13236 person-years of follow-up. The overall TB rate was 8.2 per 100 person-years (95% CI 7.7 to 8.7) during the first year of ART. TB rates varied according to diagnostic and screening practices among sites (table 1). It was 12.4 per 100 person-years in programs routinely screening for TB compared to 4.8 in programs not screening (adjusted rate ratio 0.39, 95% CI 0.20-0.79). Low baseline CD4 counts (p<0.001) and national TB incidence (p=0.001) were strongly associated with higher TB rates in sites with unlimited and free access to chest X-rays, sputum and culture, but not in sites with more limited diagnostic capabilities (Table 2). Discussion We examined TB screening, diagnostic and treatment practices regarding TB in 24 ART programs in lower income countries and were able to relate programs screening and diagnosis practices to actual TB rate in 15 sites. Only a minority of sites participating in this network routinely screened for TB before and during ART, used DOT and routinely performed INH prophylaxis. The estimated overall TB incidence rate (8.2 per 100 personyears) was comparable to the one previously found (7.4 cases per 100 person-years; 95% CI, 6.6-8.4) but significantly varied according to TB screening practices. Moreover, well-established associations between variables such as baseline CD4 or baseline national incidence rates and TB incidence rate were weak in sites not performing CHX TB screening, those ones noteworthy having more limited diagnostic capabilities. Conversely, those associations were strong among sites routinely performing free screening and diagnostic tests. Lower TB incidence rate and weak associations both suggest inappropriate TB case detection in sites not routinely screening for TB and with limited diagnosis capacities, potentially leading to a substantial amount of missed TB diagnoses. Indeed, lack of sensitive TB case detection produces false negatives (i.e. unidentified TB cases) which may bias rate ratio estimates toward the null. Since sites routinely doing CXR screening actually performed exclusively free diagnostic tests (CXR, sputum and culture), it is difficult to determine whether better case detection relied on laboratory capacities free of charge alone or active case finding procedures such as CHR TB screening. However, TB rates were negatively associated with tests unavailability or tests for which patients incurred the fees. Participating sites were heterogeneous and represented a convenience sample. As previously mentioned (ref # 6 again), an important number of patients had to be excluded because of missing data. Adjusted mortality rates were lower in sites with full and free diagnostic capacities but did not reach statistical significance (RR = 0.65 (0.341.23) p=0.183). On the other hand, rates of follow-up losses tended to be higher in those sites (RR = 1.98 (0.85-4.61) p=0.114). The generalizability of our results and their effect on mortality are therefore uncertain, but this study clearly points significant problems with TB prophylaxis, screening, diagnosis and treatment. In addition, improved TB detection rates in this study were not attributable to better patients follow-up. In the light of the results of SAPIT 10 (ref), more intensive screening for TB improves case detection and might contribute to reducing the high early mortality observed in patients starting ART in low income countries. Accurate TB diagnosis in HIV-infected patients cannot always solely rely on sputum smear microscopy. Cultures play an important role in smear negative and extrapulmonary TB diagnostics and are mentioned in algorithms and recommendations allowing earlier initiation of TB treatment in HIV patients 11, . In 12 addition, cultures are commonly considered as the closest gold standard from clinical specimens13. However, sputum smear examination by light microscopy is the only diagnostic test for tuberculosis available in many lower income countries that are most affected by tuberculosis, although only 20-50% of tuberculosis cases are estimated to be positive by this method14, this proportion being even lower in the setting of HIV infection. Therefore, active TB screening using CXR and sputum cultures that have been proposed for HIV patients15,16 are obviously not widely implemented yet. Very little is being done by governments and cooperation agencies to develop laboratory facilities in countries with a high OI-related burden, including TB. This neglect might be short-sighted as it leaves many territories incapable of performing or culture-based diagnosis or drug-resistance testing. Table 1 Patients’ important points of entry in the facility TB program Other 2 TB Diagnostic tools Chest X-rays Free of charge Charges applicable Sputum Free of charge Charges applicable Cultures Free of charge Charges applicable Not available CXR TB screening Routinely Not routinely 1 Adjusted for baseline CD4, age and sex 2 PMTCT, STI clinic, VCT, spontaneous referral n % Crude TB incidence rate / 100 personyears (95% CI) IRR (95% CI) 1 7 8 46.7 53.3 9.9 (5.0-19.7) 6.2 (2.7-14.1) 1.0 0.62 (0.22-1.72) 13 2 86.7 13.3 9.3 (5.1-17.2) 4.9 (3.0-8.1) 1.0 0.55 (0.26-1.18) 14 1 93.3 6.7 9.0 (5.1-15.8) 3.4 (2.7-4.4) 1.0 0.42 (0.23-0.74) 8 3 4 53.3 20.0 26.7 9.5 (4.1-21.7) 7.9 (2.6-24.4) 6.1 (5.4-7.0) 1.0 0.85 (0.22-3.31) 0.65 (0.27-1.57) 6 9 40.0 60.0 12.4 (6.7-22.9) 4.8 (3.6-6.5) 1.0 0.39 (0.20-0.79) Table 2 TB Factors associated with tuberculosis in the first year after HAART onset Sites with Chest X Rays TB Sites with partial TB screening and full diagnostic capacities diagnostic capacities (9 sites; n=9903) (6 sites; n=9510) Baseline CD4 cells count <25 cells/μL 25–49 cells/μL 50–99 cells/μL 100–199 cells/μL 200–350 cells/μL >350 cells/μL TB prophylaxis after HAART onset No Yes TB programme as important entry No Yes National TB incidence Per 1% increase 1 IRR (95% CI) 1 P IRR (95% CI) 1 P 1 (reference) 0.88 (0.68-1.14) 0.74 (0.59-0.94) 0.63 (0.51-0.78) 0.51 (0.39-0.68) 0.43 (0.29-0.64) <.001 1 (reference) 1.29 (0.89-1.88) 1.01 (0.72-1.43) 0.95 (0.69-1.30) 0.92 (0.64-1.32) 0.83 (0.44-1.55) n.s. 1 (reference) 0.49 (0.38-0.61) <.001 1 (reference) 0.51 (0.01-3.72) .508 1 (reference) 3.63 (1.45-9.08) .006 1 (reference) 2.0 (0.83-4.86) .125 7.33 (2.26-23.75) .001 0.57 (0.12-2.73) .483 Adjusted for age, sex and first-line antiretroviral regimen References Benson CA, Kaplan JE, Masur H, Pau A, Holmes KK. Treating Opportunistic Infections among HIVInfected Adults and Adolescents: Recommendations from CDC, the National Institutes of Health, and the HIV Medicine Association/Infectious Diseases Society of America. CID 2005; 40: S131-235 1 2 XXXX World Health Organisation. WHO Report 2008. Global tuberculosis control surveillance, planning, financing. Available at http://www.who.int/tb/publications/global_report/2008/en/index.html. (Accessed August 26, 2008) 3 Havlir DV, Getahum H, Sanne I, Nunn P. Opportunities and challenges for HIV care in overlapping HIV and TB epidemics. JAMA 2008; 300: 423-430 4 Storla DG, Yimer S, Bjune GA. A systematic review of delay in the diagnosis and treatment of tuberculosis. BMC Public Health. 2008; 8:15 5 DataCol (Data Collector). Available at http://www.who.int/datacol/home.asp. Accessed August 25, 2008. 6 The Antiretroviral Therapy in Low-Income Countries Collaboration of the Intrnational epidemiological Databases to Evaluate AIDS (IeDEA) and the ART Cohort Collaboration. Tuberculosis after Initiation of Antiretroviral Therapy in Low-Income and High-Income Countries. CID 2007; 45:1518-21 7 Connoly LE, Edelstein PH, Ramakrishnan L. Why is long term therapy required to cure tuberculosis? PLoS Med 2004; 4:e120 8 WHO Statistical Information System (WHOSIS). http://www.who.int/whosis/en/index.html (accessed August 10th 2008) 9 10 XXXX World Health Organisation. Improving the diagnosis and treatment of smear-negative pulmonary and extrapulmonary tuberculosis among adults and adolesecents. Recommendations for HIV-prevalent and resource-constrained settings. Available at http://www.who.int/entity/tb/publications/2006/tbhiv_recommendations.pdf (Accessed August 26, 2008) 11 Saranchuk P, Boulle A, Hilderbrand K, Coetzee D, Bedelu M, van Gutsem G, Meintjes G. Evaluation of a diagnostic algorithm for smear-negative pulmonary tuberculosis in HIV-infected adults. S Afr Med J 2007; 97: 517-523 12 Getahun H, Harrington M, O'Brien R, Nunn P. Diagnosis of smear-negative pulmonary tuberculosis in people with HIV infection or AIDS in resource-constrained settings: informing urgent policy changes. The Lancet 2007; 369: 2042-9. 13 Perkins M. D.. New diagnostic tools for tuberculosis. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis 2000; 4:S182-8. 14 Shah NS, Anh MH, Thuy TT, Duong Thom BS, Linh T, Nghia DT, Sy DN, Duong BD, Chau LT, Wells C, Laserson K, Varma JK. Population-based chest X-ray screening for pulmonary tuberculosis in people living with HIV/AIDS, An Giang, Vietnam. : Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2008; 12:404-10 15 Bakari M, Arbeit RD, Mtei L, Lyimo J, Waddell R, Matee M, Cole BF, Tvaroha S, Horsburgh CR, Soini H, Pallangyo K, von Reyn CF. Basis for treatment of tuberculosis among HIV-infected patients in Tanzania: the role of chest x-ray and sputum culture. BMC Infect Dis. 2008;;8:32. 16