Tracheobronchomalacia

advertisement

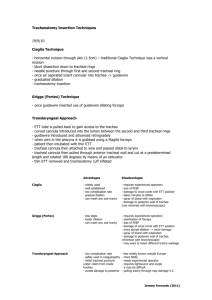

TRACHEOBRONCHOMALACIA Mita Sanghavi Goel, M.D. October 8, 2002 Description First described in 1952 in 3 infants. Caused by weakness of the tracheal wall due to softening of cartilage. Often a self-limited disease of children that resolves by the age of 3 years. Pathophysiology Dynamic collapse of the airways during expiration. Excessive dynamic compression of the major conducting airways and loss of laminar airflow cause increased airways resistance and effort of breathing, prolonged expiration, and distal air trapping. Because of inefficient cough mechanism, affected patients retain secretions and are at increased risk of developing recurrent pneumonia, bronchiectasis, and lung scarring. Clinical Presentation Intrathoracic lesion Chronic cough: recurrent, harsh, croup-like cough Wheezing and/or stridor on expiration Recurrent respiratory infections and sputum production Extrathoracic lesion Inspiratory stridor Recurrent respiratory infections and sputum production Differential diagnosis of upper airway obstruction Infectious: parainfluenza virus, bacterial membranous tracheitis, tuberculous tracheitis, rhinoscleroma Non-infectious: primary pulmonary amyloidosis, relapsing polychondritis, Wegener’s granulomatosis Other tracheal diseases: tracheal stenosis, bronchogenic cyst, intrinsic tracheal/bronchial obstruction, tracheoesophageal fistula. Pediatric entities: tracheal/bronchial atresia, tracheal bronchus. Diagnosis Requires demonstration of dynamic assessment of the trachea and bronchi throughout the respiratory cycle with demonstration of airway collapse in expiration. Tracheobronchography o Preferred method of diagnosis because of ability to assess the airways dynamically and easy to perform in intubated patients. Bronchoscopy o Of limited value because the airway may be splinted by the bronchoscope, which will reduce the dynamic compression of the airway o May not assess small airways beyond a stenosis Non-contrast fluoroscopy o Can assess the trachea well, but does not show bronchi adequately CT/MRI o Spiral and ultrafast CT and MRI with rapid acquisition sequences o Capture trachea and main bronchi, but do not reliably capture lesions because the airways move in and out of the plane of imaging during respiration Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center Residents’ Report Categorization Type 1: Intrinsic defect/immature forms of the cartilaginous portion of the trachea. Leads to increased proportion of membranous trachea. (also called primary malacia) Type 2: Extrinsic tracheal compression by cardiovascular structures, tumors, lymph nodes, or other masses. Can be congenital or acquired. (aka secondary malacia) Type 3: Result from prolonged positive pressure ventilation or infectious/inflammatory process that compromises the intrinsic cartilaginous support of the trachea. Leads to degenerationof previously normal cartilage. (also a form of secondary malacia). Treatment Steroids and bronchodilators May improve peripheral airway obstructive disease and reduce dynamic compression of airways Stents Expanding wire stents o Placed via bronchoscopy and balloon-expandable angioplasty o May cause granulomata formation, severe hemoptysis, or tracheobronchial rupture Dumon’s dedicated tracheobronchial stents o Made of molded silicon to reduce granulation tissue formation o Used more for tracheal obstruction secondary to tumors, but not well suited for diffuse tracheobronchomalacia because of stent migration and secretion retention. Y-stent o Useful for diffuse disease in the tracheobronchial tree Surgery/Tracheoplasty Reserved for patients in whom medical therapy has failed and underlying causes (tumor, etc) have been removed. References Braman S, Grillo H, Mark EJ. 44 year old man with tracheal narrowing and respiratory stridor. NEJM 1999;341(17):1292-1299. Burden RJ, Shann F, Butt W, et al. Tracheobronchial malacia and stenosis in children in intensive care: bronchograms help to predict outcome. Thorax 1999;54(6):511-517. Collard P, Freitag L, Reynaert MS, et al. Respiratory failure due to tracheobronchomalacia. Thorax 1996;51(2):224226. Furman RH, Backer CL, Dunham ME., et al. The use of baloon-expandable metallic stents in the treatment of pediatric tracheomalacia and bronchomalacia. Archives of Otolaryngology Head and Neck Surgery. 1999;125(2):203-207. Spittle N, McClusky A. Tracheal stenosis after intubation. BMJ 2000;321(7267):1000-1002. UpToDate Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center Residents’ Report