Congenital Anomalies

advertisement

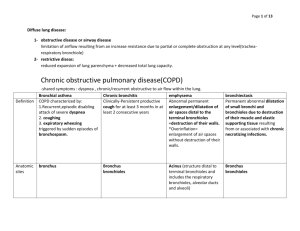

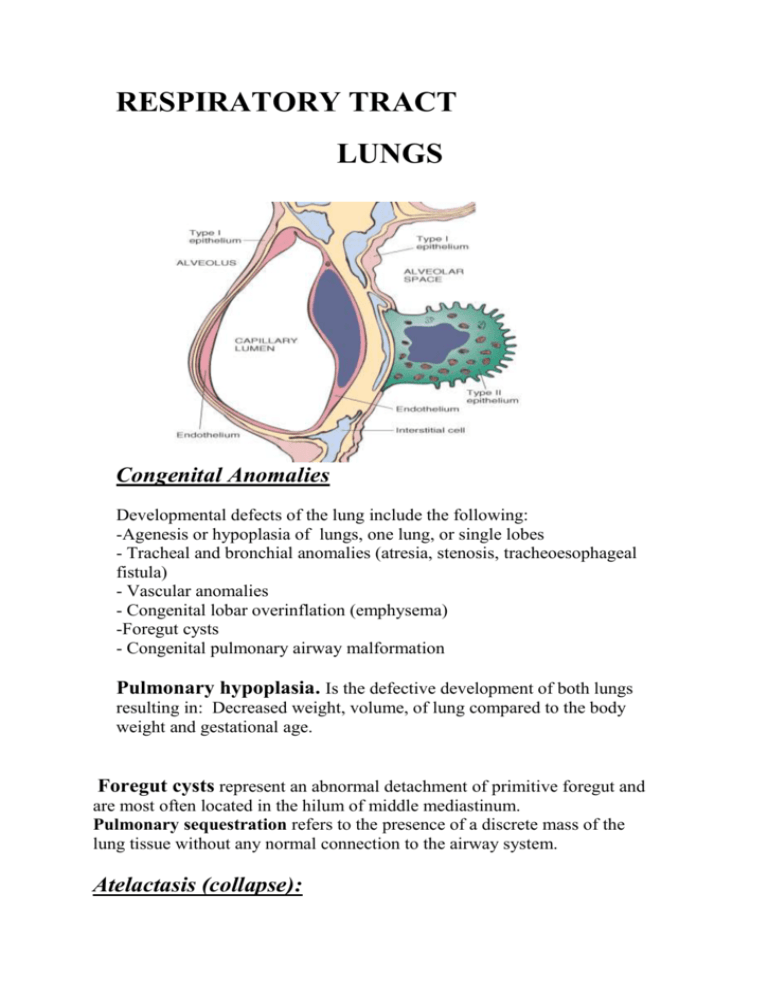

RESPIRATORY TRACT LUNGS Congenital Anomalies Developmental defects of the lung include the following: -Agenesis or hypoplasia of lungs, one lung, or single lobes - Tracheal and bronchial anomalies (atresia, stenosis, tracheoesophageal fistula) - Vascular anomalies - Congenital lobar overinflation (emphysema) -Foregut cysts - Congenital pulmonary airway malformation Pulmonary hypoplasia. Is the defective development of both lungs resulting in: Decreased weight, volume, of lung compared to the body weight and gestational age. Foregut cysts represent an abnormal detachment of primitive foregut and are most often located in the hilum of middle mediastinum. Pulmonary sequestration refers to the presence of a discrete mass of the lung tissue without any normal connection to the airway system. Atelactasis (collapse): It refers either to incomplete expansion of the lungs (neonatal atelactasis) or to the collapse of previously inflated lung, producing areas of relatively airless pulmonary parenchyma. Acquired ate.: Encountered mainly in adults, devided into resorption (or obstruction), compression, and contraction ate.. ♦RESORPTION ATE.:Is the consequences of complete obstruction of an airway, which leads to resorption of the oxygen trapped in the dependent alveoli, since lung volume is diminished, the mediastinum shifts toward the atelactatic lung. ♦COMPRESSION ATE.:Results whenever the pleural cavity is partially or completely filled by fluid exudates, tumor, blood, or air, when air pressure impinges on and threatens the function of the lung and mediastinum. ♦CONTRACTION ATELACTASIS:Occurs when local or generalized fibrotic changes in the lung or pleura prevent full expansion. ♦ significant atelactasis reduces oxygenation and predispose to infection. ♦ it is a reversible disorder (except that caused by contraction). OBSTRUCTIVE VERSUS RESTRICTIVE PULMONARY DISEASES Depending on the pulmonary function test pulmonary diseases can be classified into two categories: 1- Obstructive diseases (OPD), characterized by an increase in resistance to airflow owning to partial or complete obstruction at any level of respiratory tract. 2- restrictive diseases (RPD), reduce expansion of the lung parenchyma, with reduce total lung capacity. Obstructive diseases (OPD):- emphysema. - Chronic bronchitis. - Asthma. - And broncheactasis. EMPHYSEMA It is a condition of the lung characterized by abnormal permanent enlargement of the airspaces distal to the terminal bronchioles, accompanied by destruction of their walls and without obvious fibrosis. ♦ overinflation: enlargement of the airspaces unaccompanied by destruction. TYPES: According to the anatomic distribution in the lobule: - centriacinar. - Panacinar. - Paraseptal. - Irregular. 1- CENTRIACINAR EMPHYSEMA: - involve the central or proximal parts of the acini (formed by the respiratory bronchioles ), sparing the distal part. - More common in the upper lobes. - The wall often contain large amount of black pigment. - It occurs predominantly in heavy smokers , often in association with chronic bronchitis. 2- PANACINAR E.:- the acini are uniformly enlarged from the level of the respiratory bronchiole to the terminal blind alveoli. - More commonly in the lower zone of the lung, and most severe in the bases. - Associated with alpha1 antitrypsin deficiency. 3- DISTAL ACINAR E.:- The distal part is predominantly involved. - Occur adjacent to the areas of fibrosis, scarring, or atelactasis. - Usually more severe in the upper part of the lung. 4- Airspaces enlargement with fibrosis (irregular emphysema), - acinus irregularly involved. - Almost invariably associated with scarring. - Usually asymptomatic and insignificant. PATHOGENESIS: For the destruction of the alveolar walls the most plausible hypothesis is the ◘ protease antiprotease mechanism aided by ◘ oxidant-antioxidant imbalance. Alveolar wall destruction result from an imbalance between protease (mainly elastase) and antiprotease in the lung.this theory based on important observations; the homozygous patients with a deficiency of protease inhibitor (α1-AT) have markedly enhanced tendency to develop pulmonary emphysema. This theory also explains the deleterious effect of cig. Smoking both increased elastase availability and decreased antielastase activity occur in smokers. Smoking also cause oxidant- antioxidant imbalance, tobacco smoke contain abndant amount of free radicals (reactive oxygen species which deplete antioxidant mechanisms in the lung, thereby inciting tissue damage. Figure 15-7 Pathogenesis of emphysema. The protease-antiprotease imbalance and oxidantantioxidant imbalance are additive in their effects and contribute to tissue damage. 1 antitrypsin (1 -AT) deficiency can be either congenital or "functional" as a result of oxidative inactivation. See text for details. IL-8, interleukin 8; LTB4 , leukotriene B4 ; TNF, tumor necrosis factor. MORPHOLOGY: GROSS: voluminous lungs, large blebs or bullae may bee seen. MIC: there are abnormally large alveoli separated by thin septa, there are even larger abnormal airspaces.often the respiratory bronchioles and vasculature of the lung deformed and compressed. Figure 15-6 A, Centriacinar emphysema. Central areas show marked emphysematous damage (E), surrounded by relatively spared alveolar spaces. B, Panacinar emphysema involving the entire pulmonary architecture. CHRONIC BRONCHITIS Chronic bronchitis, so common--among habitual smokers and inhabitants of smog-laden cities. When persistent for years, it may (1) progress to chronic obstructive airway disease, (2) lead to cor pulmonale and heart failure, or (3) cause atypical metaplasia and dysplasia of the respiratory epithelium, providing a rich soil for cancerous transformation. Important definitions in bronchitis include the following: Chronic bronchitis per se is defined clinically. It is present in any patient who has persistent cough with sputum production for at least 3 months in at least 2 consecutive years, in the absence of any other identifiable cause. * In simple chronic bronchitis, patients have a productive cough but no physiologic evidence of airflow obstruction. * Some individuals may demonstrate hyperreactive airways with intermittent bronchospasm and wheezing. This condition is called chronic asthmatic bronchitis. - Finally, some patients, especially heavy smokers, develop chronic airflow obstruction, usually with evidence of associated emphysema, and are classified as showing obstructive chronic bronchitis. Pathogenesis. The primary or initiating factor in the genesis of chronic bronchitis appears to be chronic irritation by inhaled substances such as tobacco smoke (90% of patients are smokers) and grain, cotton, and silica dust. Bacterial and viral infections are important in triggering acute exacerbation of the disease. Both sexes and all ages may be affected, but chronic bronchitis is most frequent in middle-aged men. Chronic bronchitis is 4 to 10 times more common in heavy smokers regardless of age, sex, occupation, and place of dwelling. The earliest feature of chronic bronchitis is hypersecretion of mucus in the large airways, associated with hypertrophy of the submucosal glands in the trachea and bronchi.2° Proteases released from neutrophils, such as neutrophil elastase and cathepsin, and matrix metalloproteinases, stimulate this mucus hypersecretion. As chronic bronchitis persists, there is also a marked increase in goblet cells of small airways—small bronchi and bronchioles—leading to excessive mucus production that contributes to airway obstruction. It is thought that both the submucosal gland hypertrophy and the increase in goblet cells are a protective metaplastic reaction against tobacco smoke or other pollutants. Many of the respiratory epithelial effects of environmental irritants are believed to be mediated through the epidermal growth factor (EGF) receptor. Morphology. Grossly, there may be hyperemia. swelling, and edema of the mucous membranes, frequently accompanied by excessive mucinous mucopurulent secretions layering the epithelial surfaces. Sometimes, heavy casts of secretions and pus fill the bronchi and bronchioles. The characteristic histologic features of chronic bronchitis are: ◘ chronic inflammation of the airways (predominantly lymphocytes) ◘ and enlargement of the mucus-secreting glands of the trachea and bronchi. ◘Although the numbers of goblet cells increase slightly, the major increase is in the size of the mucous glands. ◘The bronchial epithelium may show squamous metaplasia and dysplasia. ◘There is marker narrowing of bronchioles caused by goblet cell metaplasia, mucus plugging, inflammation, and fibrosis. ◘ In the most severe cases, there may be obliteration of lumen due to fibrosis (bronchiolitis obliterans). Clinical Features. The cardinal symptom of chronic bronchitis is a persistent cough productive of sputum. For years, no other respiratory functional impairment is present but eventually, dyspnea on exertion develops. With time, and usually with continued smoking, other elements of COPD may appear, including hypercapnia, hypoxernia, and mild cyanosis. ASTHMA it is a chronic inflammatory disorder of the airways that causes recurrent episodes of wheezing, breathlessness, chest tightness, and cough especially at night or in the early morning. TYPES: 1- atopic; most common type, usu begins at childhood, triggered by environmental antigens, e.g.dust, pollens, animal danders, and foods. A positive family history of atopy is common, asthmatic attacks are often preceded by allergic rhinitis, urticaria, or eczema. 2- Nonatopic asthma: most commonly triggered by RTI especially viral, a positive family history is uncommon.serum IgE level is normal, there is no other associated allergies, pathogenesis; due to hyperirritability of the bronchial tree; virus induce inflammation of the respiratory mucosa lowers the threshold of the subepithelial vagal receptors to irritants. 3- Drug-Induced asthma: Aspirin- sensitive asthma. 4- Occupational asthma: simulated by fumes, organic, gases, and chemical dusts. Morphology; 1- whorls of epith (Curshman spirals). 2- Thickening of the b.m. of the bronchial epith. 3- Edema, and infl. Infil. 4- Increase in the size of the submucosal glands. 5- Hypertrophy of s.m. of bronchial wall. Bronchiectasis It is a disease characterized by permanent dilation of bronchi and bronchioles caused by destruction of the muscle and elastic tissue, resulting from or associated with chronic necrotizing infections. To be considered bronchiectasis, dilation should be permanent; reversible bronchial dilaion often accompanies viral and bacterial pneumonia. because of better control of lung infections, bronchiectasis is now an uncommon condition. It is manifested clinically by high fever, and expectoration of copious amounts of fouling, purulent sputum. Bronchiectasis develops in association with a variety of conditions, which include the following: • Postinfectious conditions, including necrotizing pneumonia caused by bacteria (Mycobacterium tuberculosis, Staphylococcus aureus, Haemophilus influenzae, Pseudomonas), viruses (adenovirus, influenza virus, HIV), and fungi (Aspergillus species) • Bronchial obstruction, owing to tumor, foreign bodies, and occasionally mucus impaction, in which the bronchiectasis is localized to the obstructed lung segment • Other conditions, including rheumatoid arthritis, systemic lupus erythematosus, inflammatory bowel disease, and post-transplantation (chronic lung rejection, and chronic graft-versus-host disease after bone marrow transplantation) Etiology and Pathogenesis. Obstruction and infection are the major influences associated with bronchiectasis, and it is likely that both are necessary for the development of full-fledged lesions, although either may come first. After bronchial obstruction (e.g., by mucus impaction, tumors, or foreign bodies), normal clearing mechanisms are impaired, there is pooling of secretions distal to the obstruction, and there is inflammation of the airway. Conversely, severe infections of the bronchi lead to inflammation, often with necrosis, fibrosis, and eventually dilatation of airways. cystic fibrosis. In this disorder, the primary defect in chloride transport leads to impaired secretion of chloride ions into mucus, low sodium and water content, defective mucociliary action, and accumulation of thick viscid secretions that obstruct the airways. This leads to a marked susceptibility to bacterial infections, which further damage the airways. In primary ciliary dyskinesia, an autosomal-recessive syndrome, poorly functioning cilia contribute to the retention of secretions and recurrent infections that in turn lead to bronchiectasis. There is an absence or shortening of the dynein arms that are responsible for the coordinated bending of the cilia. Approximately half of the patients with primary ciliary dyskinesia have Kartagener syndrome (bronchiectasis, sinusitis, and situs inversus or partial lateralizing abnormality) . The lack of ciliary activity interferes with bacterial clearance, predisposes the sinuses and bronchi to infection, and affects cell motility during embryogenesis, resulting in the situs inversus. Males with this condition tend to be infertile, owing to ineffective mobility of the sperm tail. Morphology. Bronchiectasis usually affects the lower lobes bilaterally, particularly air passages that are vertical, and is most severe in the more distal bronchi and bronchioles. When tumors or aspiration of foreign bodies leads to bronchiectasis, the involvement may be sharply localized to a single segment of the lung. The airways are dilated, sometimes up to four times normal size. These dilations may produce long, tubelike enlargements (cylindrical bronchiectasis) or, in other cases, may cause fusiform or even sharply saccular distention (saccular bronchiectasis). Characteristically, the bronchi and bronchioles are sufficiently dilated that they can be followed, on gross examination, directly out to the pleural surfaces. By contrast, in the normal lung, the bronchioles cannot be followed by ordinary gross dissection beyond a point 2 to 3cm removed from the pleural surfaces. On the cut surface of the lung, the transected dilated bronchi appear as cysts filled with mucopurulent secretions. The histologic findings: there is an intense acute and chronic inflammatory exudation within the walls of the bronchi and bronchioles, associated with desquamation of the lining epithelium and extensive areas of necrotizing ulceration. There may be squamous metaplasia of the remaining epithelium. In some instances, the necrosis completely destroys the bronchial or bronchiolar walls and forms a lung abscess Clinical Course. Bronchiectasis causes severe, persistent cough; expectoration of foul-smelling, sometimes bloody sputum; dyspnea and orthopnea in severe cases; and occasional life-threatening hemoptysis. Obstructive ventilatory insufficiency can lead to marked dyspnea and cyanosis. Cor pulmonale, metastatic brain abscesses, and amyloidosis are less frequent complications of bronchiectasis.