Obstructive Pulmonary Diseases of the Lower Airways…It’s not all Emphysema!

advertisement

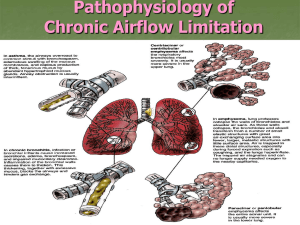

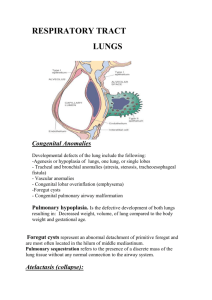

Obstructive Pulmonary Diseases of the Lower Airways…It’s not all Emphysema! Karin and Jason Kuhl 4/14/04 What’s your differential diagnosis? 52 yo male with chronic cough, dyspnea, and occasional wheezing 100 pack year smoking history PFT’s demonstrate an obstructive pattern Obstructive Pulmonary Diseases Any disease affecting the upper or lower airways can be associated with obstruction of airflow from the lungs. This presentation will focus on those pathological processes primarily affecting the lower airways, including: – – – – – Emphysema Chronic Bronchitis Asthma Bronchiectasis Bronchiolitis obliterans (constrictive bronchiolitis) COPD Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is a general term lumping emphysema, chronic bronchitis, and asthma together. COPD is not used to describe the other disease states resulting from chronic airflow obstruction. Disadvantages of using the term COPD: – Other obstructive conditions are often over-looked. – Pathologic and physiologic mechanisms of these diseases are different. – Prognosis and treatment are disease specific. Emphysema Defined by the American Thoracic Society as “the permanent enlargement of the air spaces distal to the terminal bronchiole as a result of destruction of the alveolar walls without significant fibrosis.” Three principle types: Centriacinar (centrilobular) – Predominantly in upper lung zones. – Associated with smoking & pneumoconiosis. Panacinar (panlobular) – More progressive, and with more severe symptoms because it involves the lower lung zones (areas of greater gas exchange). – Associated with alpha-1-antitrypsin deficiency. Distal acinar (paraseptal) – Focal or multifocal disease. – Involves distal alveolar sacs and ducts, resulting in subpleural blebs and bullae. – More likely to cause spontaneous pneumothorax. Pathology of the secondary pulmonary lobule: Normal B. Centriacinar C. Panacinar D. Paraseptal A. Webb1 Protease-Anti-protease Theory: Cotran2 Emphysema results from the destructive effect of high protease activity in subjects with low anti-protease activity. Normal lung and emphysema: Marc Gosselin, MD Airflow obstruction is due to the loss of elastic recoil of the lung parenchyma. Lynch3 Clinical manifestation: Insidious onset Dyspnea Noncyanotic (pink puffer) Mild cough +/- Increased sputum +/- Wheezing AP diameter Usually thin Chest radiographic findings: Poor in evaluating very early disease due to limitations in small airway visualization. As the disease progresses, radiograph can directly demonstrate disease pathology, as well as indirect signs of increased lung compliance and air-trapping. Identification of emphysema on CXR: Direct identification: – Irregular, asymmetric areas of decreased lung density. – Vascular deficiency: Rapidly attenuating peripheral pulmonary arteries, may be absent peripherally Increased branching angles Smaller-than-expected caliber – Bullae – Saber-sheath trachea Indirect identification: – Signs of hyperinflation: Flattened diaphragm Sterno-diaphragmatic angle >90o on lateral Increased width of retrosternal air space Increased AP diameter Increased intercostal distance Emphysema Giant Bullous Emphysema (“Vanshing Lung” Syndrome) Giant bulla with missing vascular shadows. Emphysema: Trachea Saber-sheath trachea. www.radiology.vcu.edu CT findings: Relatively well-defined, low attenuation areas with very thin (invisible) walls, surrounded by normal lung parenchyma. As disease progresses: – Amount of intervening normal lung decreases. – Number and size of the pulmonary vessels decrease. – +/- Abnormal vessel branching angles (>90o), with vessel bowing around the bullae. Centrilobular Emphysema Emphysematous Bullae www.ctsnet.org/doc/6761 Chronic Bronchitis Presence of a chronic, productive cough for 3 or more months, in at least 2 consecutive years, when all other causes of cough have been excluded (clinical diagnosis). Pathology: Hypertrophy of the submucusal glands in the trachea and bronchi, and an increase in goblet cells in the small bronchi and bronchioles, leads to excessive mucus production and obstruction. Caused by tobacco smoke and other inhaled pollutants, not infection. – Infection appears to be significant in maintaining the disease. Cotran2 Airflow obstruction caused by: Mucus plugging of large and small airway lumens. Airway alterations: – Inflammatory infiltration – Bronchiolar wall fibrosis Clinical manifestation: Cough Copious sputum Cyanotic (blue bloater) +/- dyspnea +/- rhonchi/wheezing Usually obese Chest radiographic findings: It is difficult to know which radiographic findings are attributable to chronic bronchitis, rather than to emphysema, because they commonly coexist. Chest radiograph is often not reliable at detecting or excluding chronic bronchitis. – CXR is helpful in excluding diseases that can clinically mimic chronic bronchitis (TB, tumor, bronchiectasis, abscess). Principle Radiographic abnormalities: Thickening of bronchial walls Overinflation* Oligemia* Evidence of Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension *The overinflation and oligemia seen in chronic bronchitis may also be due to superimposed emphysema. Chronic Bronchitis Normal Exacerbation Webb, RW1 Arrows show parallel linear shadows indicating bronchial wall thickening. Chronic Bronchitis Webb, RW1 Bronchogram shows dilation, narrowing, and abrupt termination (arrows) of various small bronchi. CT findings: Limited literature on CT features of chronic bronchitis. Bronchial wall thickening has been documented in patients with chronic bronchitis, but has also been observed in patients without respiratory symptoms. Chronic Bronchitis CT? Quantitative CT: Spirometically triggered images at 10% and 90% vital capacity (VC) have been reported to be able to distinguish patients with chronic bronchitis from those with emphysema. – Patients with emphysema had significantly lower mean lung attenuation at 90% VC than normal subjects or patients with chronic bronchitis. – Attenuation was the same for normal subjects and those with chronic bronchitis. Asthma A chronic, relapsing inflammatory disorder characterized by hyperactive airways, leading to episodic, reversible bronchoconstriction. Two Types: – Extrinsic: initiated by a type I hypersensitivity reaction, induced by exposure to an extrinsic antigen. – Intrinsic: initiated by diverse, non-immune mechanisms (stress, pulmonary infection, exercise, cold, etc.). Pathology: Large & small airway mucus plugging Airway infiltrated with inflammatory cells Tissue edema & epithelial disruption Sub-basement membrane collagen deposition Hypertrophy of smooth muscle Hypertrophy of submucosal glands Cotran2 Obstruction is caused by: Bronchoconstriction Airway wall edema and inflammatory thickening Mucus plugging Clinical Manifestation: Cough (usually worse at night) Dyspnea Wheezing Chest tightness Symptoms often worse with: – – – – – Exercise Allergens Smoke Changes in weather And many others… Chest radiographic findings: Bronchial wall thickening: Most Common Air-trapping (hyperinflation found in 25%) Atelectasis: From mucus plugging +/- bronchial constriction +/- bronchial dilatation Asthma: Airway Thickening Most Common Finding Asthma: Airway Thickening and Hyperinflation Thin Section CT findings: Bronchial wall thickening Mucoid impaction Mosaic lung attenuation with air trapping – Findings may be reversible with pharmacologic treatment. Centrilobular thickening Asthma: Airway Thickening and Lucent Areas of Decreased Ventilation (Mosaic Perfusion) Bronchiectasis A chronic, necrotizing infection of the bronchi & bronchioles, leading to abnormal, permanent dilatation of the involved airways. May develop in association with: – Bronchial obstruction: localized (tumor, foreign body) or diffuse (asthma, chronic bronchitis) – Congenital/Hereditary: CF, Kartagener’s syndrome – Necrotizing pneumonia Incidence markedly decreased, due to the advent of antibiotics and immunizations. Pathology: Obstruction and infection are the major influences associated with bronchiectasis. Bronchial obstruction leads to atelectasis of airways distal to the obstruction. Bronchial wall inflammation & intraluminal secretions cause dilatation of the patent airways proximal to the obstruction. Pathology: Process becomes irreversible if the obstruction persists or if there is added infection. Vicious cycle of recurrent/chronic infections perpetuates the airway inflammation & dilatation, leading to extensive endobronchial destruction. FYI: There are different types of bronchiectasis: Cylindrical – Airway wall is regularly/uniformly dilated. Varicose – Greater dilatation with alternating areas of constriction and dilatation. Cystic – Progressive, distal enlargement resulting in sac-like Most severe terminations of the airways. – Cystic spaces can be several centimeters in diameter and contain air-fluid levels. Clinical Manifestations: Chronic cough and expectoration of copious, purulent sputum. +/- dyspnea +/- hemoptysis +/- fever, weight loss, anemia, clubbing Chest radiographic findings: Earliest finding is bronchial wall thickening With further dilatation & wall thickening, see “tram lines” & “ring shadows” (Curved reticular opacities). There is often initially some generalized overinflation of involved lobe (from concurrent small airways involvement). In advanced stages, areas of atelectasis and collapse develop. Bronchiectasis: Pathology and Bronchogram Historical Imaging Method of Diagnosis Bronchiectasis: Cystic Fibrosis Most frequent CT findings: Most frequent Less frequent Lack of tapering of the bronchial lumen Bronchial wall thickening Bronchial dilatation Visualized peripheral bronchi Mucus plugging Bronchiectasis Radiology 2002; 225: 663-672 Arrows demonstrating various grades of bronchial wall thickening, with concurrent mucus plugging (arrowheads) in some bronchial lumens. Cystic Bronchiectasis www.emedicine.com Bronchiectasis Signet ring? or Solitaire ring? Radiology 1999; 212: 67-68 “Signet ring” sign “Question Dogma” …Marc Gosselin, MD Bronchiolitis Obliterans Pathologic fibrosis (scarring) of the small airways, leading to luminal narrowing and irreversible airflow obstruction. Virtually any inflammatory process that leads to scarring can cause BO. Bronchiolitis Obliterans May be seen as the result of: – Childhood viral infection (Swyer-James Syndrome) – Mycoplasma pneumonia – Toxic fume inhalation Common pulmonary problem in patients with: – Rheumatoid arthritis (especially if taking penicillamine) – Chronic GVH following BMT – Chronic rejection after heart-lung or lung transplant Pathology: Submucosal and peribronchiolar inflammation and fibrosis cause concentric narrowing of the bronchiolar lumen and mucus stasis. Complete obstruction of the airway occurs by either fibrosis squeezing the lumen shut, or intraluminal plug formation. Alveolar ventilation beyond the obstruction continues via the terminal conducting airways, adding to the degree of air trapping. Clinical manifestation: Cough Dyspnea Fatigue Diagnosis of BO: – Irreversible airflow obstruction with a FEV1 <60% of predicted in the absence of emphysema, chronic bronchitis, asthma, or other causes of airway obstruction. Chest radiographic findings: Chest radiograph often subtle findings. May be able to discern hyperinflation due to: – Air trapping – Vessel attenuation – Bronchial wall thickening Involvement of one lung usually represents Swyer-James Syndrome. Classic Bronchiolitis Obliterans (History and CT), But given a diagnosis of emphysema. (We diagnosis what we know, so know a lot!) CT findings: Mosaic attenuation Bronchial dilatation Air trapping – Expiratory HRCT facilitates detection of areas of decreased attenuation. Bronchiolitis Obliterans Radiology 2000; 216: 472-477 •Single arrows: air trapping •Double arrows: subtle areas of relatively increased lung attenuation represent normal, collapsing lung Inspiratory & expiratory views of bronchiolitis obliterans Marc Gosselin, MD Obstructive Pulmonary Diseases of the Lower Airways Imaging can be helpful in diagnosing lower airway obstructive disease; however, there is much overlap in findings. It is necessary to integrate the clinical presentation, abnormal physiology, and imaging findings to correctly diagnose the disorder. Consider ALL obstructive pathology when first establishing your differential diagnosis. Remember, it’s NOT all emphysema… References: 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. Webb, RW. The Radiologic Clinics of North America: Imaging of obstructive Pulmonary Disease. W.B. Saunders Company. Philadelphia, PA. Vol. 36(1). January, 1998. Cotran RS, Kumar V, Collins T. Robbins Pathologic Basis of Disease: 6th ed. W.B. Saunders Company. Philadelphia, PA. 1999. pp: 711-717. Lynch DA, Newell JD, Lee JS. Imaging of Diffuse Lung Disease. B.D. Decker Inc. Hamilton, Ontario. 2000. pp: 171-200. Sharma V, Shaaban AM, Berges G, Gosselin M. The radiological spectrum of small-airway disease. Seminars in Ultrasound, CT, and MRI. 23(4): 339351, 2002. Webb RW, Muller NL, Naidich DP. High-Resolution CT of the Lung: 3rd ed. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. Philadelphia, PA. 2001. pp: 467-546.