References

advertisement

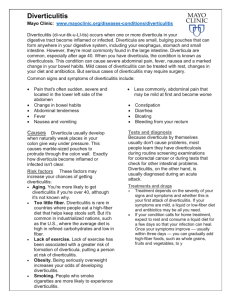

DISMINUYENDO EL USO DE OSTOMÍAS EN LA DIVERTICULITIS Dr. Stanley Goldberg Introduction The presence of Colonic diverticulae in older patients is a common finding. As the percentage of older Americans increases, it is likely that the surgeon will likewise more frequently encounter both uncomplicated and complicated diverticulitis. Furthermore, as new approaches are described and refined both for nonoperative and operative treatment, it is imperative that surgeons continuously reassess the evaluation and care of diverticulitis patients. This presentation discusses current approaches to the diagnosis, work-up and treatment of diverticulitis, with a special focus on perforated sigmoid diverticular disease. Diagnosis The initial diagnosis of uncomplicated diverticulitis is usually fairly straightforward based on patient history, physical examination, and laboratory studies. The use of CT scan in every patient suspected of having diverticulitis has been proposed, but such an approach is not cost-conscious, nor is it necessary for patients with uncomplicated diverticulitis. We obtain a CT scan when the patient shows no clinical improvement after 24-48 hours of medical treatment, if there is clinical deterioration, or if a pelvic abscess is suspected at initial presentation. If the patient appears to have uncomplicated diverticulitis and responds appropriately to medical treatment, a CT scan is unnecessary. In such cases (when diverticulae have never been demonstrated) an enema contrast study should be performed four to six weeks after recovery to confirm the presence of diverticulae. Furthermore, contrast enema imaging can be useful in evaluating the extent of the disease, thus aiding in decisions concerning the advisability of elective resection. Finally, contrast enema may also indicate to rule-out a neoplastic process. Non-Surgical Management Medical management consists of bowel rest, frequent reevaluations by the physician, and intravenous antibiotics. Regimens should be aimed at gram negative aerobes as well as anaerobes, especially Bacteroides species. Duration of antibiotic treatment is based on clinical response and usually lasts five to seven days in cases of uncomplicated diverticulitis. We believe that a patient who is improved to the point of discharge does not require further oral antibiotic therapy. Percutaneous drainage techniques have significantly altered the approach to the patient with a diverticular abscess. The only contraindications to percutaneous drainage are an abscess, which is inaccessible, pathology which is inappropriate (primarily phlegmonous), a patient who is too high-risk (coagulopathy), and cases which require emergent surgical intervention irrespective of the presence of the abscess (peritonitis). We percutaneously drain intra-abdominal and pelvic abscesses in all other stable patients. Catheter management is aimed at complete drainage of the abscess cavity and prevention of drain plugging. Sterile irrigation is gently used to unclog the catheter every six to eight hours and as needed. Multiple catheters may be required. There is controversy concerning the need and timing of further imaging studies following catheter placement. A repeat CT scan is obtained if the patient fails to improve clinically after catheter placement search for evidence of incomplete drainage or an undrained abscess. Controversy also surrounds the question of duration of drainage. If the patient displays the appropriate clinical improvement and the catheter drainage is minimal, fistulogram is performed with water-soluble contrast via the catheter. If no identifiable cavity remains, even in the presence of a demonstrable fistula to the colon, the catheter is removed. Clinically stable patients who continue to have moderate catheter drainage are sent home on oral antibiotics. When their drainage subsides, they undergo fistulogram and follow-up as described. Elective Resection Perhaps the greatest area of controversy concerns the indications for elective resection following resolution of diverticulitis treated medically. In agreement with the majority of authors, we recommend surgical resection of the involved segment in patients who have suffered two or more documented attacks of uncomplicated diverticulitis. Likewise, elective resection should be performed following one attach of documented uncomplicated diverticulitis in patients who require chronic immunosuppression. In ability to distinguish diverticular disease from malignancy also clearly requires resection. Finally, colovesicular and colovaginal fistulae rarely close with conservative therapy, and the presence of either is an indication for surgical resection. Our approach to elective resection differs from that of many authors in regards to the following three groups of patients. Elective Resection Following Successful Precutaneous Drainage We do not automatically recommend elective resection in every patient whose first bout of diverticulitis is complicated by an abscess if that abscess is successfully drained and the inflammation resolves. Four to six weeks following catheter removal, a contrast study and/or endoscopic exam is performed. As described above, findings on these studies help determine the need for elective resection. Elective Resection in the Immunocompromised Patient For patients who require long-term immunosuppression and are known to have diverticulosis but have no history of diverticulitis, some authors advocate elective, prophylactic sigmoid resection. We disagree, as it has not been conclusively demonstrated that a significant portion of these patients will develop diverticulitis, and subjective all such immunocompromised patients to a major operation is not without risk. Of course we recognize that diverticulitis is more difficult to diagnose and rarely if ever responds to conservative treatment in this patient group. Thus, a high index of suspicion and an aggressive treatment approach is necessary in the immunocompromised patient with diverticulitis. Surgical Options in Perforated Sigmoid Diverticular Disease The Hartmann procedure is the only operative approach we recommend in patients with perforated diverticulitis and feculent peritonitis. In the vast majority of patients with perforated diverticulitis and purulent peritonitis, we likewise utilize the Hartmann procedure. However, in a small subset of such patients (stable patients, minimal peritonitis, early exploration), resection (with or without intraoperative lavage), primary anastomosis, and creation of a diverting splitloop ileostomy is acceptable. Such an approach allows for a simpler and safer split-loop ileostomy takedown, avoiding the significant morbidity of colostomy takedown and reanastomosis following a Hartmann procedure. When an abscess is inadvertently entered during exploration of a patient without peritonitis, resection and primary anastomosis with or without the creation of a diverting split-loop ileostomy is indicated. Finally, patients with abscesses that can be removed en bloc without spillage, should undergo resection and primary anastomosis without diversion. Extent of Resection The entire distal sigmoid colon must be resected, leaving only proximal rectum for performance of anastomosis or pouch closure, as resection proximal to rectum has been demonstrated to have a higher rate of recurrent diverticulitis in the sigmoid remnant. The proximal extent of resection, on the other hand, is not defined anatomically. Proximally the colon should be divided where the bowel is soft, even in the presence of diverticulae. The area of resection may be so limited that mobilization of the splenic flexure is unnecessary. Summary There are many controversies concerning the treatment of diverticulitis in patients, which would best be resolved by prospective studies. Percutaneous drainage of abscesses now allows an increasing number of diverticulitis patients to be successfully treated without operation. We believe that a significant number of such patients may not require subsequent elective resection. Likewise, not all younger patients require elective resection following resolution of their first attack of diverticulitis. Nor does prophylactic resection seem wise in all immunocompromised diverticulosis patients without an inflammatory history. Finally, the role of resection with primary anastomosis, both with and without loop diversion, continues to expand. References 1. Ryan P. Emergnecy resection and anastomosis for perforated sigmoid diverticulitis. Aust NZ J Surg 1974; 44:16-20. 2. Killingback M. Management of perforative diverticulitis. Surg Clin N Amer 983; 63:97-115. 3. Hinchey EF, Schaal PG, Richards GK. Treatment of perforated diverticular disease of the colon. Adv Surg 1978; 12:85-109. 4. Sydney University Teaching Hospitals: survey on acute diverticulitisperitonitis. Unpublished. 5. Berry AR, Turner WH, Mortensen NJMcC, Kettlewell GW. Emergency surgery for complicated diverticular disease. Dis Colon Rectum 1989; 32:849-54 6. Corder, AP, Williams, JD. Optimal operative treatment in acute septic complications of diverticular disease. Ann R Coll Surg Engl 1990; 72:82-6. 7. Tudor RG, Farmakis N, Keighley MR. National audit of complicated diverticular disease: analysis of index cases. Br J Surg 1994; 81:7302. 8. Wedell j, Banzhaf G. Chaoui R, Fischer R, Reichmann J. Surgical management of complicated colonic diverticulitis. Br J Surg 1997; 84:380-3. 9. Elliott TB, Yego S, Irvin TT. Five-year audit of the acute complications of diverticular disease. Br J Surg 1997;84:535-9. 10. Khan AL, Heys SD, Ah-Sec AK, Eremin O, Crofts TJ. Surgical management of the septic complications of diverticular disease. Ann R Coll Engl 1995;77:16-20. 11. Setti-Carraro PG, Magenta A, Segala M, Ravizzini C, Nespoli A, Tiberio G. Chir-Ital 1999;51:31-6. 12. Ambrosetti P, Grossholz M, Becker C, Terrier F, Morel Ph. Computed tomography in acute left colonic diverticulitis. BR J Surg 1997;84:5324. 13. Wroblicka JT, Kuligowska E. One step needle aspiration and lavage for the treatment of abdominal and pelvic abscesses. AM J Roentgenol 1998;170:197-1203. 14. Stabile BE, Puccio E, Van Sonnenberg E, Neff C. Preoperative percutaneous drainage of diverticular abscess. Am J Surg 1990;159:99-105. 15. Hachigian MP, Honickman S, Eisenstat TE, et al. Computer tomography in the initial management of acute left-sided diverticulitis. Dis Colon Rectum 1992;35:1123-34. 16. Bernini A, Spencer MP, Wong D, Rothenberger DA, Madoff RD. Computere tomography guided percutaneous abscess drainage in intestinal disease. Dis Colon Rectum 1997; 40:1009-13. 17. Sarin s, Boulos PB. Long-term outcome of patients presenting with acute complications of diverticular disease. Ann R Coll Surg Engl 1994;76:117-20. 18. Krukowski ZH, Koruth NM, MathesonNA. Evolving practice in acute diverticulitis. BR J Surg1985;72:684-6. 19. Rothenberger, DA, Wiltz O. Surgery for complicated diverticulitis. Surg Clin N AM 1993;73:975-95. 20. Alanis A, Papanicolaou GK, Tadros RR, Fielding LP. Primary resection and anastomosis for treatment of acute diverticulitis. Dis Colon Rectum 1989;32:933-9. 21. Hartmann H, Nouveau procede d’ablation des cancers de la partie terminale du colon pelvien. Trentieme Congress de Chirugie, Strasbourg, France 1921;411-4. 22. Maggard MA, Thompson JE, Schmit PJ, Chandler CF, Bennion RS, Au A, Hines OJ. Same admission colon resection with primary anastomosis for acute diverticulitis. Am Surg 1999; 65:927-30. 23. Hoemke M, Treckman j, Schmitz R, Shah S, Complicated diverticulitis of the sigmoid: a prospective study concerning primary resection with secure primary anastomosis. Dig Surg 1999;16:420-4. 24. Makela J, Vuolio S, Kiviniemi H, Laitinen S. Natural history of diverticular disease. When to operate? Dis Colon Rectum 1998; 41:1523-8. 25. O’Sullivan GC, Murphy D, O’Brien MG, Ireland A. Laparoscopic management of generalized peritonitis due to perforated colonic diverticular disease. Am J Surg 1996;171:432-4. 26. Franklin Jr ME, Dorman JO, Jacobs M, Plasencia G, Is laporoscopic surgery applicable to complicated colonic diverticular disease? Surg Endosc 1997;11:1021-5. 27. Wong WD, Wexner SD, Lowry A, Vernava III A. Practice parameters for the treatment of sigmoid diverticulitis – supporting documentation. Prepared by the standards task force: The American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons. Dis Colon Rectum 2000;43:289-97. 28. Armbrosetti P, Robert JH, Witzig J-A, et al: Acute left colonic diverticulitis in young patients. J Am Coll Sur 179:156-160, 1994. 29. Armbrosetti P, Robert JH, Witzig J-A, et al: Acute left colonic diverticulitis: a prospective analysis of 226 consecutive cases. Surgery 115:546-550, 1994. 30. Murray JJ, Schoetz DJ, Coller JA, et Al: Intraoperative colonic lavage and primary anastamosis in nonelective colon resection. Dis Colon Rectum 34;527-531, 1991. 31. Roberts PL, Veidenheimer MC: Current Management of Diverticulitis, Adv in Surg 27;198-208, 1994. 32. Schoetz DJ, Uncomplicated diverticulitis: indications for surgery and surgical management. Surg Clin North Am 73:965-974, 1993.