Temporal bone fracture and its complication

advertisement

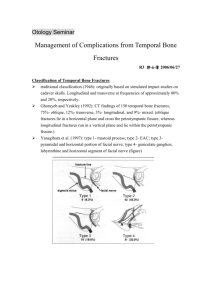

Temporal bone fracture and its complication Mar. 6th, 2002. 整理者: R3 邱贊仁 Temporal bone fracture (TBF): 1. Clinical criteria: head trauma history, PE: otorrhea, hemotympanum, facial nerve paralysis. 2. Clinical and radiological criteria: head trauma history, PE, HRCT. *Although HRCT has improved the radiological diagnosis of temporal bone fractures, the diagnosis must often be based on clinical findings alone4. Incidence of TBF: 30~75% blunt head trauma1 14~22% skull fracture2 2% head-injured patients6 Etiology of TBF: Motor vehicle accidents2, assult, fall, motorcycle, pedestrian… Children1: 0~4 y/o: falls 4~14 y/o: Motor vehicle accidents TBF classification: (arbitrary) 1. The fracture line relative to the long axis of the petrous bone. Longitudinal: parallel Transverse: perpendicular mixed Longitudinal Transverse long axis of petrous parallel perpendicular frequency most common, 70~90% 20~30% external ear canal laceration frequent, bleeding middle ear bleeding ossicles disruption frequent, hemotympanum common, CHL otic capsule involve common, SNHL vestibular involve mild, concussive effect facial paralysis 10~25%2, often delay onset 30~50%2, immediately CSF leak may be loss, concussive or otic capsule fracture Traumaedema facial n interruption less common common 2. Yanagihara N3 (3 D helical CT): type 1, 2, 3, 4 (4a, 4b) surgical & radiological significance. Evaluation: Head injury patients presented to the emergency room @ABC principles(maintain respiratory & circulatory function): first @Evaluate neurologic status @Facial n function evaluation: (initial facial n evaluation is very important)2,4 (conscious vs unconscious pts---stimulating paingrimace) @ear, EAC, tympanic membrane(TM) evaluation: EAC laceration, bony fracture TM perforation: location, shape(slit, triangular, stellate) Ear bleeding: D/D from EAC lacerated skin or middle ear active bleeding @middle ear active bleeding: possible CSF leakage *How to manage the ear bleeding (ear canal packing or not)? *How to diagnose CSF otorrhea or rhinorrhea? @Vestibular system evaluation: Nystagmus (important) Nystagmus: Direction change or vertical nystagmus: central injury Destructive lesion: toward the noninvolved side Irritative lesion: toward the involved side @Audiologic evaluation: Weber test(Tunning fork) at ER PTA, speech discrimination, acoustic reflex @Radiologic evaluation: Potential skull base fracture: HRCT of temporal bone (s contrast) HRCT: 1.5~2.0mm thickness, axial view, coronal view if possible. Complication: 1. TM traumatic perforation & external auditory canal stenosis Remove blood clot from the EAC by suction gently. EAC laceration: severestented with a pack to prevent stenosis Fracture-dislocation of EAC: reduction by Killian nasal speculum and EAC pack Initial relocation the fracture-dislocation of EAC is beneficial and important. Scarstenosis difficult to correct TM perforation: Slit-like P: spontaneous healing Triangular or stellate P: (big P size) Small-angled pickgently tease this flap back into its anatomic position Transcanal paper myringoplasty Otics is not suggested for dry, clean, traumatic TM perforation. 2. CSF otorrhea, rhinorrhea, otorhinorrhea (potential meningitis2): Incidence: 26% TBF4 Diagnosis1: (1) PE(serosanguineous drainage from the ear or nose) (2) History of antecedent temporal bone trauma (3) Determination of the fluid as CSF How to determine the otorrhea/rhinorrhea as CSF? (1) Filter paper: halo sign or double ring. (highly suggestive) (2) β-2 transferrin(100% sensitivity, 95% specificity)5: a protein found in CSF and perilymph not in blood, nasal secretion,or middle ear secretion. advantages: small sample size for analysis(<1 mL) resistance to contamination by other fluids require no special handling or refrigeration (3) Glucose content test(biochemical): unreliable False positive rate:45~75% (4) Sugar dipstick: unreliable, particular in the presence of blood (5) Nuclear medicine evaluation: intrathecal injection of fluorescein or a radioactive carrier substance Management: Medical (conservative) approach: no other intracranial injury. >90% resolve spontaneously(7~10days)1,2. (1) bed rest (2) head of bed elevation (3) avoid of straining: constipation, coughing, nose blowing (stool softener, anti-tussive, anti-histamine) (4) lumbar drain: decrease CSF pressure Surgical repair:(indication) (1) CSF leak persists for 7~10 days (meningitis chance)2 (2)A large petrous bone defect1 (3)Late onset CSF leak1 (4)Brain herniation1 (5)Recurrent episodes of meningitis1 *Antibiotic prophylaxis: necessary? Is it beneficial in reducing post-traumatic meningitis? Canniff et al9: 1800 head injury, CSF otorrhea 1.4%, 20%meningitis (1) increased risk of developing meningitis2: CSF leak>7days, concurrent infection (2) benefit: Brodie et al2 (CSF fistula present) (3) not benefit: Hoff et al2, Lee et al1, inadequate management and affect culture results9 (4) adequate prophylaxis Abx9: broad-spectrum Abx and cross BBB 3. Facial paralysis: Incidence1: before CT use: 11% recent:3~4% Evaluation: (1) House-Brackmann grading system(I~VI) DEFS (2) Topographic diagnosis: simple & definitive. Great discrepancy Schirmer tear test Acoustic (stapedial reflex) Taste tests Salivary tests (3) Electrical tests: reliability be challenged Evaluate the physiologic extent of n damage Predict prognosis, determine treatment. Many times exams: D/D degeneration/regeneration Maximal nerve excitability test(MST) Electroneurography/Evoked electromyography(EnoG) Electromyography(EMG) Onset: immediate vs delay onset (initial evaluationvery important) Immediate onset: severed facial n chance delay onset: traumaedematous process Surgical intervention vs Medical management Surgical intervention Medical management Onset immediate delay severity complete incomplete ENoG >=90%, Fisch et al. <90% Fracture type transverse longitudinal Medical management: steroid, careful facial n monitoring Surgical management: The key factor in the decision to decompress is whether a severed nerve is suspected. Barrs et al4: empty axonal tubules 5 days after trauma, nearly complete at 21 days Animal study: for crushed or severed facial nretrograde degeneration within 30 days. Regeneration was prevented. Most common site for facial n injury: (1) Distal labyrinthine segment near the geniculate ganglion8 (perigeniculate region) (2)Mastoid segment(distal to the second genu) Facial nerve exploration and decompression For n repair, release edemaprevent fibrosis, scarringregeneration Severe n degeneration Fisch Lambert & Brackmann Transection n. 30% 23% Bony impingement 20% 38% Intraneural hematoma 50% 8% Localized swelling 0 31% (1) transmastoid supralabyrinthine approach (2) translabyrinthine approach: total loss of auditory & vestibular function (3) middle fossa approach (4) combined transmastoid and middle fossa approach: for preserved hearing Conclusion(Summary) 1. Facial n function initial evaluation at ER is very important. Delayed onset of facial paralysis, surgical decompression is rarely indicated. 2. CSF fistula generally close spontaneously with conservative management within 1 week. 3. Increased risk of developing meningitis: CSF fistula>7 days, concurrent infection. 4. Prophylactic antibiotics: controversial CSF fistula present: use2 Broad spectrum and cross BBB9. Detailed method for facial n decompression: discussion at next section References: 1. Lee D, Honrado C, Har-El G, et al. Pediatric temporal bone fractures. Laryngoscope 1998;108:816-21. 2. Brodie HA, Thompson TC. Management of complications from 820 temporal bone fractures. Am J Otol 1997;18(2):188-97 3. Yanagihara N, Murakami S, Nishihara S. Temporal bone fractures inducing facial nerve paralysis: A new classification and its clinical significance. ENT J 1997; 76(2):79-86 4. Nageris B, Hansen MC, Lavelle WG, et al. Temporal bone fractures. Am J Emerg 5. 6. 7. 8. 9. Med 1995;13(2):211-4. McGuirt WF, Stool SE. Cerebrospinal fluid fistula: the identification and management in pediatric temporal bone fractures. Laryngoscope 1995;105:359-64 Eby TL, Pollak A, Fisch U. Intratemporal facial nerve anastomosis: A temporal bone study. Laryngoscope 1990;100:623-6. Ylikoski J. Facial palsy after temporal bone fracture: light and electron microscopic findings in two cases. J Laryngo Otol 1988;102:298-303. Eby TL, Pollak A, Fisch U. Histopathology of the facial nerve after longitudinal temporal bone fracture. Laryngoscope 1988;98:717-20. Kinney SE. Trauma to the middle ear and temporal bone. Otolaryngology head and neck surgery. Mosby, 1998;3076-87. 10. Dobie RA. Tests of facial nerve function. Otolaryngology head and neck surgery. Mosby, 1998;2757-66.