Local Anesthetics

advertisement

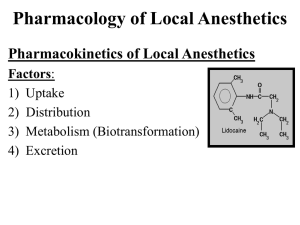

Local anesthetics History: For centuries, the Peruvian people have appreciated the pharmacologic actions of the leaves of the Erythroxylon coca, a shrub growing high in the Andes mountains. Chewing or sucking these leaves produces a sense of well-being. The plant ash releases an alkaloid in a form that can be absorbed across mucous membranes. This alkaloid is more commonly known today as cocaine. The pure alkaloid of cocaine was isolated in 1880, and its pharmacodynamic properties were further investigated. In 1884, cocaine was used clinically as a local anesthetic in ophthalmology, dentistry, and surgery. In 1905, the first synthetic local anesthetic, procaine, was developed and became the prototype for these agents. There are currently 16 chemical agents used in local anesthesia; lidocaine, bupivacaine, and tetracaine are the most commonly used in clinical practice. Local anesthetics are used to decrease pain, temperature, touch proprioception, and skeletal muscle tone. The degree of these actions is dependent on dose and concentrations of the drug, degree of hydrophobicity, and integrity of the application site. Local anesthetics are used in a variety of clinical situations, from topical application to the skin or mucosa membranes to injectable agents used for peripheral, central, or spinal nerve block. Some agents are used for specific indications in preparations intended for anorectal or ophthalmic use. Mechanism of Action: All local anesthetics reversibly block nerve conduction by decreasing nerve membrane permeability to sodium. This decreases the rate of membrane depolarization, thereby increasing the threshold for electrical excitability. All nerve fibers are affected, albeit in a predictable sequence: autonomic, sensory, motor. These effects diminish in reverse order. Since these drugs can also block sodium channels in myocardial tissues, an antiarrhythmic action is created. Lidocaine and procainamide are routinely used as antiarrhythmics. Mexiletine and tocainide, oral congeners of lidocaine, possess a mechanism of action similar to lidocaine and are also used as antiarrhythmics. Currently, mexiletine and tocainide are not available in topical or injectable preparations for local anesthetic purposes. Finally, lidocaine has also been used as an alternative agent in the treatment of status epilepticus. While the mechanism of this effect is unclear, it is likely that blockade of neuronal sodium channels may be involved. Distinguishing Features: Since the mechanism of action is similar, local anesthetics are selected based on their pharmacodynamic and pharmacokinetic features. Ideally, the agent should possess low systemic toxicity, have a rapid onset of action, have a duration of action long enough to complete the intended procedure, and not be irritating to the tissue. Local anesthetics are listed according to their basic chemical class. Typically, local anesthetics are grouped as either "amides" or "esters". The "esters" include the prototype procaine, and also benzocaine, butamben picrate, chloroprocaine, cocaine, proparacaine, and tetracaine. These agents are derivatives of paraaminobenzoic acid and are hydrolyzed by plasma esterases. The "amides" include the prototype lidocaine, and also bupivacaine, dibucaine, etidocaine, mepivacaine, prilocaine, and ropivacaine. The amides are derivatives of aniline and are metabolized primarily in the liver, and the metabolites are then excreted renally. Lidocaine, mepivacaine, and tetracaine also may have some biliary excretion. Dyclonine and pramoxine do not fit into either chemical classification and might be suitable alternatives in patients with allergies to amides or esters. Bupivacaine is commonly used for epidural anesthesia in obstetrics because of its motor-sparing properties and long duration although its systemic toxicity is greater than less potent agents such as lidocaine or mepivacaine. Selection of a local anesthetic is based largely on its pharmacokinetics. The site and route of administration can influence the characteristics of an agent. Most local anesthetics have a rapid onset when administered parenterally for infiltrative anesthesia, the fastest being lidocaine (0.5-1 minute) followed by prilocaine (1-2 minutes). The average onset of action for the remaining agents is between 3-5 minutes. The exception is tetracaine, which can take up to 15 minutes. The onset of action is longer with epidural administration, averaging approximately 5-15 minutes for most local anesthetics. Procaine (15-25 minutes), tetracaine (20-30 minutes), and bupivacaine (10-20 minutes) all have slightly slower onsets of action when administered epidurally than the other agents. The duration of action of the injectable anesthetic agents is important in their selection for various procedures. Procaine and chloroprocaine are the shortest-acting agents (0.250.5 hours), followed by lidocaine, mepivacaine, and prilocaine, which have slightly longer durations of action (0.5-1.5 hours). The longer-acting agents include tetracaine (23 hours), bupivacaine (2-4 hours), etidocaine (2-3 hours), and ropivacaine. Ropivacaine exhibits a duration of 8-13 hours when used for peripheral nerve block but the effective analgesia when administered epidurally is only 2.5-6 hours. Epinephrine prolongs the duration of action of most local anesthetics, however, this is not always a consistent finding. Spinally administered local anesthetics tend to have a slightly shorter duration of action compared with other routes of administration. Applied topically, local anesthetics reach peak effect at different times when applied to mucous membranes. Benzocaine is the fastest (1 minute), followed by lidocaine = cocaine < pramoxine < tetracaine < dyclonine and < dibucaine. All of the topical products have a duration of action ranging from about 30 minutes to an hour. Cocaine's effects can last up to 2 hours after topical application, and dibucaine has the longest duration of action at 3-4 hours. The topical local anesthetics are used for skin and mucous membrane anesthesia. Most agents are used for both indications, except dibucaine, butamben picrate, and pramoxine, which are not used on mucous membranes. Pramoxine was found to be too irritating to the eyes and nose. Dyclonine and cocaine are not used in skin disorders, perhaps because they are well absorbed through the skin. Tetracaine and proparacaine are available as ophthalmic preparations. Benzocaine and pramoxine are also included in a variety of anorectal preparations. Benzocaine candy or gum is used as a diet aid in combination with dieting. It works by decreasing the ability to detect degrees of sweetness by altering taste perception. Adverse Reactions: Systemic absorption of local anesthetics can produce increased serum concentrations, resulting in toxicity in the CNS or the cardiovascular system. The longer the duration of action, the higher the potential for toxicity, which can include neurolysis with sloughing and necrosis of surrounding tissue. Parenteral local anesthetics are often coadministered epinephrine or other local vasoconstrictor to delay systemic absorption, prolong duration of action, and promote local hemostasis. Local hypersensitivity reactions are more likely to occur with the "ester" type of local anesthetics. The "amide" type of local anesthetics has not demonstrated cross-sensitivity with the esters. Some of the topical preparations contain tartrazine and sulfites and should be used with caution in patients with these hypersensitivities.