Context - University of Cambridge

advertisement

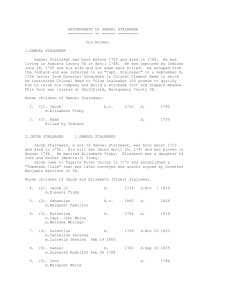

Meaning, Context and Cognition, Uniwersytet Łódzki, 24-26 March 2011 Context: From Intentions to Two-Dimensional Semantics K. M. Jaszczolt University of Cambridge 1 Paul Grice: Intentions ‘A meantNN something by x’: A uttered x with the intention of inducing a belief by means of the recognition of this intention. Grice 1957 in 1989, p. 219 2 ‘U meant something by uttering x’ is true iff, for some audience A, U uttered x intending: (1) A to produce a particular response r (2) A to think (recognize) that U intends (1) (3) A to fulfil (1) on the basis of his fulfilment of (2). Grice 1969 in 1989, p.92 3 Questions and objectives: ? Aspects end extent of compatibility of Gricean intentionbased pragmatics with the ‘formal pragmatics’ in twodimensional semantics (advocated by Stalnaker, e.g. 1999) 4 Questions and objectives: ?Aspects and extent of compatibility of Gricean intentionbased pragmatics with the ‘formal pragmatics’ in twodimensional semantics (advocated by Stalnaker, e.g. 1999) ?Compatibility of the notions of context, semantic content, role of intentions 5 Questions and objectives: ?Aspects and extent of compatibility of Gricean intention-based pragmatics with the ‘formal pragmatics’ in two-dimensional semantics (advocated by Stalnaker, e.g. 1999) ?Compatibility of the notions of context, semantic content, role of intentions ?Lessons for contextualism 6 • possible worlds • truth conditions • Sentence meaning determines content relative to context. • Content determines truth value relative to a possible world. 7 Kaplan’s character and content (1989a, b) 8 Kaplan’s character and content (1989a, b) Stalnaker’s propositional concept (1978, 2011) 9 Conclusions for contextualism: Truth-Conditional Pragmatics (Recanati, e.g. 2004, 2010) Default Semantics (Jaszczolt, e.g. 2005, 2010) 10 Context Kaplan (1989a): context = occasions of use Context (index) provides the necessary parameters for semantics: an agent, time, location, and world. Character/content theory: a speaker utters a sentence in a context, indexical expressions are associated with referents, and then the sentence is evaluated in circumstances of evaluation. 11 Contexts vs. circumstances of evaluation: An indexical expression (I, he, now, that) may have different referents in different contexts but the same referent when evaluated in circumstances of evaluation (counterfactual situations) = direct reference 12 Indexicals (he) have context-sensitive character; content varies with context. Non-indexicals (dog) have fixed character, the same content in all contexts but the content varies with circumstances of evaluation. 13 A proposition comprises a set of circumstances of evaluation (possible worlds) and determines a set of possible contexts. 14 Proper names: Proper names can be ambiguous (unlike indexicals) pre-semantic role of context (‘Aristotle’) Contextual feature of ‘the causal history of a particular proper name expression in the agent’s idiolect’ (1989a: 562) = determining what word was used (pre-semantic) 15 Kaplan’s context – summary: Three roles of context: (i) pre-semantic (disambiguation); (ii) assigning denotation to a character; (iii) counterfactual situations i= (w,t,l,a,…) 16 Context is a metaphysical rather than a cognitive notion 17 Stalnaker’s context ‘To understand what a speaker is doing when she says how things are, we need to understand how she is distinguishing between different ways that things might be. … one should be able to say something general about the kind of thing we are talking about when we talk about possibilities, counterfactual situations, or possible worlds.’ Stalnaker (1999: 2) 18 Assertion • Assertions (speech acts) are sayings which have some effect on the hearer • Assertion expresses the speaker’s belief and the intention that he hearer adopt/hold this belief. (cf. Brown and Cappelen 2011) 19 Propositional concept (i) Enumerating the truth values of a sentence in different possible worlds; (ii) Enumerating the referents assigned to the indexical expression. (1) ‘You are to blame.’ 20 Propositional concept T F T ‘you’ according to S (‘you’ = A) T F T ‘you’ according to A (’you’= A) F T F S’s beliefs A’s beliefs ‘you’ according to B (‘you’ = B) B’s beliefs 21 Propositional concept T F T ‘you’ according to S (‘you’ = A) T F T ‘you’ according to A (’you’= A) F S’s beliefs T A’s beliefs F ‘you’ according to B (‘you’ = B) B’s beliefs 22 Propositional concept • Horizontal dimension = what is said in different contexts • Vertical dimension = possible worlds as contexts • Diagonal = the proposition that is true at a world and context iff what is expressed in this context and world is true there. (‘Whatever is said by S is true’) 23 From metaphysics to intentions Propositions as sets of possible worlds Centered possible worlds (pairs: possible world + time and person in the world) (Stalnaker e.g. 1979, 2011) 24 Context in two-dimensional semantics Context is understood as common background, represented by a context-set, meaning a set of possible worlds that are compatible with what is presupposed by the speaker in a situation of discourse. When all the presuppositions in the speaker’s context-set coincide with those in the addressee’s context-set , the context is nondefective. 25 Two-dimensional semantics and Gricean intentions Context is understood as common background, represented by a context-set, meaning a set of possible worlds that are compatible with what is presupposed by the speaker in a situation of discourse. When all the presuppositions in the speaker’s context-set coincide with those in the addressee’s context-set , the context is nondefective. 26 Towards intentions Stalnaker: what is said differs on the horizontal dimension; intention recognition/ascription by the addressee cf. speaker’s meaning – addressee’s meaning debate 27 Towards intentions • Context as intention ascription there is no restriction against going beyond slots in the logical form (resolving indexicals), to top-down processing in twodimensional semantics: (2) Everyone […] has seen King’s Speech. (3) Tom is a fine friend. 28 Kaplan and intentions Afterthoughts (1989b) ‘directing intention’ The character of an indexical expression (its ‘linguistic meaning’, say, contextually salient male as the meaning of ‘he’) can be associated with different contents thanks to the directing intention to refer. 29 This intention creates the ‘potential’ for distinct referents. The intention operates, according to Kaplan, on the ‘preformal’ level (1989b: 588) and hence is not part of semantics. The next step, the evaluation of an occurrence of an expression in circumstances of evaluation, i.e. the theory of content, should ideally belong, according to Kaplan (p. 575), to pragmatics. 30 ‘The same demonstrative can be repeated, with a distinct directing intention for each repetition of the demonstrative. This can occur in the single sentence, “You, you , you and you can leave, but you stay”, or in a single discourse, “You can leave. You must stay.”’ Kaplan (1989b: 587) (cf. a repetition of ‘today’ refers to a different day only when the context has changed) 31 ‘The directing intention is the element that differentiates the “meaning” of one syntactic occurrence of a demonstrative from another, creating the potential for distinct referents…’ (p. 588). 32 Directing intention vs. intended meaning: One can mistakenly refer to B intending to refer to A. Directing intention is then the intention to refer to B. = ‘forensic element to our ordinary concept of what is said’, Perry (2009: 191): 33 ‘Saying something is often a social act, which has effects on others in virtue of the words used, their meanings, and other publicly observable indications of the speaker’s intentions (“perlocutionary effects”).’ What is said in the case of a mistaken demonstration will differ form audience to audience. 34 we need instead a concept of locutionary content that is arrived at through directing intentions. ?No limit to pragmatic contribution to locutionary content and no clear delimitation: 35 ‘…the primary reason we think it is worth developing a semitechnical concept, locutionary content, as an explication of what is said, is that the latter concept has a heavy forensic aspect, that is tied to its daily use in not only describing utterances but assigning responsibility for their effects, but isn’t helpful for theoretical purposes.’ Korta and Perry (2007: 105) 36 A synthesis: Kaplanesque context and post-Gricean contextualism ‘If we think of the formal role played by context within the model-theoretic semantics, then we should say that context provides whatever parameters are needed.’ Kaplan (1989b: 591) (cf. top-down processing, e.g. Recanati 2004) 37 The state of the art ‘… a theoretically useful concept of what is said, explicated as locutionary content, can be developed’ and it ‘will play more or less the roles contemplated by both Grice and the new theorists of reference.’ Korta and Perry (2007: 110) 38 Lessons for contextualism: Use the two-dimensional matrix for ‘non-indexicals’ overcoming the speaker’s meaning/hearer’s meaning dilemma e.g. (4) (5) The piglet has finished his porridge. The mice are asking you to forgive them. (Thai) 39 Reason for modelling what is said on locutionary content: ‘…in general (i.e. not only in the special case of indexicals), the propositional contribution of an expression is not fully determined by the invariant meaning conventionally associated with the expression type but depends upon the context.’ Recanati (2010: 17) 40 Locutionary content and Default Semantics (Jaszczolt 2005, 2009, 2010) Pragmatic compositionality Primary meaning (cf. locutionary content?) is orthogonal to the what is said/what is implicated distinction 41 The logical form of the sentence can not only be extended but also replaced by a new semantic representation when the primary, intended meaning demands it. Such extensions or substitutions are primary meanings and their representations are merger representations in Default Semantics. There is no syntactic constraint on merger representations. 42 (6) Child to mother: Everybody has a bike. (6a) All of the child’s friends have bikes. (6b) Many/most of the child’s classmates have bikes. (6c) The mother should consider buying her son a bike. (6d) Cycling is a popular form of exercise among children. 43 (6) Child to mother: Everybody has a bike. (6a) All of the child’s friends have bikes. (6b) Many/most of the child’s classmates have bikes. (6c) The mother should consider buying her son a bike. (6d) Cycling is a popular form of exercise among children. 44 Primary meaning: combination of word meaning and sentence structure (WS) merger representation Σ social, cultural and cognitive defaults (CD) world-knowledge defaultspm (SCWDpm) conscious pragmatic inference pm (from situation of discourse, social and cultural assumptions, and world knowledge) (CPIpm) Secondary meanings: Social, cultural and world-knowledge defaultssm (SCWDsm) conscious pragmatic inferencesm (CPIsm) Fig. 1: Utterance interpretation according to the processing model of the revised version of Default Semantics • Two-dimensional perspective allows for the formalization of pragmatic additions (effects of ‘modulation’, ‘enrichment’,…) as sets of alternatives. • The main content () resembles locutionary content: there may not be a principle differentiating it from secondary contents (unlike what is said/implicated), but is easily identifiable in conversation. • The ‘pre-formal’ use of context in two-dimensional semantics is better conceived of as built into a contextualist semantic theory, as a contributor to . 46 Indexicals vis-à-vis top-down modulation: An experiment and a hypothesis NCEs (necessary contextual elements, Larson et al. 2009: 80) (7) Irene: What shoes are you wearing to dinner? Sam: I’m going to wear these shoes. FACT: Sam has decided to wear the shoes in the upstairs closet, not the ones he is currently putting on. 47 • Rate of ‘false’ responses: 86-92% • Cf. contradiction control items: 98-99% The difference is significant; subjects distinguish between linguistically supplied and contextually supplied information, even when there is no/little doubt concerning the referent. 48 ?hypothesis: if bottom-up processing pairs with top-down processing, then the two-dimensional analysis can be applied equally to cases of modulation, including concept construction. 49 ?hypothesis: if bottom-up processing pairs with top-down processing, then the two-dimensional analysis can be applied equally to cases of modulation, including concept construction. Questions arising: implications for the term ‘indexical’, ‘hidden-indexical theory’, the role of sense/mode of presentation vis-á-vis meaning eliminativism, late Wittgenstein and evidence from neuropragmatics, e.g. Pulvermüller 2010) 50 Select references: Brown, J. and H. Cappelen. 2011. ‘Assertion: An introduction and overview’. In: Brown, J. and H. Cappelen (eds). Assertion: New Philosophical Essays. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1-17. Jaszczolt, K. M. 2005: Default Semantics: Foundations of a Compositional Theory of Acts of Communication. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Jaszczolt, K. M. 2009. Representing Time: An Essay on Temporality as Modality. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Jaszczolt, K. M. 2010. ‘Default Semantics’. In: B. Heine and H. Narrog (eds.) The Oxford Handbook of Linguistic Analysis. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 193-221. Kaplan, D. 1989a. ‘Demonstratives’. In: J. Almog, J. Perry, and H. Wettstein (eds). Themes from Kaplan. New York: Oxford University Press, 481-563. Kaplan, D. 1989b. ‘Afterthoughts’. In: J. Almog, J. Perry, and H. Wettstein (eds). Themes from Kaplan. New York: Oxford University Press, 565-614. Korta, K. and J. Perry. 2007. ‘Radical minimalism, moderate contextualism’. In: G. Preyer and G. Peter (eds). Context-Sensitivity and Semantic Minimalism: New Essays on Semantics and Pragmatics. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 94-111. 51 Larson, M. et al. 2009. ‘Distinguishing the Said from the Implicated using a novel experimental paradigm’. In: U. Sauerland and K. Yatsushiro (eds). Semantics and Pragmatics: From Experiment to Theory. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.74-93. Perry, J. 2009. ‘Directing intentions’. In: J. Almog andP Leonardi (eds). The Philosophy of David Kaplan. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 187-201. Predelli, S. 2005. Contexts: Meaning, Truth, and the Use of Language. Oxford: Clarendon Press. Pulvermüller, F. 2010. ‘Brain-language research: Where is the progress?’. Biolinguistics 4. 255-88. Recanati, F. 2004. Literal Meaning. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Recanati, F. 2010. Truth-Conditional Pragmatics. Oxford: Clarendon Press. Stalnaker, R. 1978. ‘Assertion’. Syntax and Semantics 9. New York: Academic Press. Reprinted in R. Stalnaker, 1999, Context and Content, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 78-95. Stalnaker, R. 2011. ‘The essential contextual’. In: Brown, J. and H. Cappelen (eds). Assertion: New Philosophical Essays. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 137-150. 52