Communication and Decision Making in Pediatric

advertisement

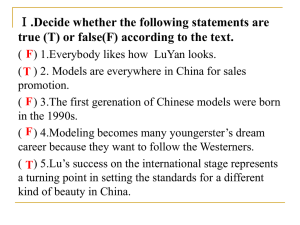

Communication in Pediatric Palliative Care Mike Harlos MD, CCFP, FCFP Professor and Section Head, Palliative Medicine, University of Manitoba Medical Director, WRHA Adult and Pediatric Palliative Care Erin Shepherd RN, MN Clinical Nurse Specialist, WRHA Pediatric Palliative Care The presenters have no conflicts of interest to disclose Objectives • Review fundamental components of effective communication with children and their families • Explore boundary issues when addressing difficult scenarios in palliative care • Discuss potential barriers to effective communication in palliative care • Consider an approaches/framework to challenging communication issues http://palliative.info Parents’ Priorities For Pediatric Palliative Care Meyer EC, Burns JP, Griffith JL, Truog RD. Parental perspectives on end-of-life care in the pediatric intensive care unit. Crit Care Med 2002; 30(1):226-231. n = 56 parents Case 1 • 7 month old infant with severe anoxic brain injury due to balloon aspiration • life-sustaining treatment in the PICU withdrawn, was being transferred ward for palliative care • as he was being wheeled out of his ICU room in his bed, his father noticed that he no longer had an intravenous line “Where is his IV line? How is he going to get fluids?” Case 2 • 18 yo female with CF, in her first hospitalization on the adult wards at HSC • resp. failure, on BiPAP, prognosis 1-2 days • clinical team called for help with discussing goals of care, as she seemed to want CPR but no invasive ventilation Case 3 • 17 yo with widely metastatic Ewing’s sarcoma • ward team would like goals of care addressed, particularly around CPR • she does not want to talk about anything potentially related to dying Titrating Opioids In Treating Pain Children Look Up Recommended Dose Titrating Truth In Communicating With Children “Look Up Recommended Dose”: •Consider developmental understanding of issue •Ask parents & health care team what child understands •Check with parents if/how they would like information shared Start conservatively, usually with lower end of recommended range unless severity of distress dictates otherwise Observe/assess response, titrate accordingly Start Conservatively: • I’m wondering what made you ask this today? • Can you yell me what you understand is going on? Observe/assess response, titrate accordingly Connecting • A foundational component of effective communication is to connect / engage with that person… i.e. try to understand what their experience might be • If you were in their position, how might you react or behave? • What might you be hoping for? Concerned about? • This does not mean you try to take on that person's suffering as your own • Must remain mindful of what you need to take ownership of (symptom control, effective communication and support), vs. what you cannot (the sadness, the unfairness, the very fact that this person is dying) Macro-Culture Micro-Culture How does this family work? & Talking about Death with Children Who Have Severe Malignant Disease Kreicbergs et al NEJM 2004; 351(12):1175-1186. Children < 17 yrs with malignancy Dx between 1992 and 1997 n = 429 parents (76% of eligible) of 368 children Questionnaire 4 – 9 yrs after child’s death after initial telephone contact, exploring parents’ perceptions of their child’s awareness of dying and communication with their child about dying Talking about Death with Children … ctd Kreicbergs et al NEJM 2004; 351(12):1175-1186. Did you talk about death with your child at any time? n = 147 (34 %) n = 282 No (66 %) Yes Do you regret having done so? Do you regret not having done so? No parents regretted having talked with their children about dying Yes No Overall: 27% 73% Sensed Child Aware Of Dying: 47% 53% Did Not Sense Child Aware: 13% 87% Identify and facilitate communication Communicating with seriously ill children Sourkes, Barbara; “Armfuls of Time” “To shield the child from the truth may only heighten anxiety and cause the child to feel isolated, lonely, and unsure about whom to trust.” “While the diagnosis is an event in time, ‘telling’ is a process over time” “How to inform the child of the diagnosis should be decided by the parents in consultation with the staff…” “Fluidity is the hallmark of the child’s response to diagnosis” Communicating ctd Sourkes, Barbara; “Armfuls of Time” “A general guideline is to follow the child’s lead: he or she questions facts or implications only when ready, and that readiness must be respected.” “It is the adult’s responsibility to clarify the precise intent of any question and then to proceed with a step-by-step response, thereby granting the child options at each juncture” “Offering less information with the explicit invitation to ask for more affords a safety gauge of control for the child.” Responding To Difficult Questions 1. Acknowledge/Validate and Normalize “That’s a very good question, and one that we should talk about. Many people in these circumstances wonder about that…” 2. Is there a reason this has come up? “I’m wondering if something has come up that prompted you to ask this?” 3. Gently explore their thoughts/understanding • “It would help me to have a feel for what your understanding is of what is happening, and what might be expected” • “Sometimes when people ask questions such as this, they have an idea in their mind about what the answer might be. Is that the case for you?” 4. Respond, if possible and appropriate • If you feel unable to provide a satisfactory reply, then be honest about that and indicate how you will help them explore that DISCUSSING PROGNOSIS “How long does he have?” 1. Confirm what is being asked 2. Acknowledge / validate / normalize 3. Check if there’s a reason that this is has come up at this time 4. Explore “frame of reference” (understanding of illness, what they are aware of being told) 5. Tell them that it would be helpful to you in answering the question if they could describe how the last month or so has been 6. How would they answer that question themselves? 7. Answer the question 22 “First, you need to know that we’re not very good at judging how much time someone might have... however we can provide an estimate. We can usually speak in terms of ranges, such as months-to-years, or weeks-to-months. From what I understand of his condition, and I believe you’re aware of, it won’t be years. This brings the time frame into the weeks-to-months range. From what we’ve seen in the way things are changing, I’m feeling that it might be as short as a couple of weeks, or perhaps up to a month or two” Anatomy of Decision Making • Context forms the background on which decisions are considered… past experiences, present circumstances, anticipated developments • Information is the foundation on which decisions are made Clinical information – facts, numbers; the “what” Values / belief systems / ethical framework; the “who”… this includes is the patient/family and the health care team • Goals are the focus of decisions – dialogue around health care decision (or any decision, for that matter) should be framed in terms of the hoped-for goals • Communication is the means by which information is shared and discussion of goals takes place Preemptive Decisions • The clinical course at end of a progressive illness tends to be predictable... some issues are “predictably unpredictable” (such as when death will occur) • Many concerns can be readily anticipated • Preemptively address communications issues: food/fluid intake sleeping too much are medications causing the decline? how do we know he/she is comfortable? can he/she hear us? don’t want to miss being there at time of death how long can this go on? what will things look like? Preemptive Discussions • “You might be wondering…” • “At some point soon you will likely wonder about…” • “Many parents in such situations think about whether… 29 Patient/Family Understanding and Expectations Health Care Team’s Assessment and Expectations Starting the Conversation – Sample Scripts “I know it’s been a difficult time recently, with a lot happening. I realize you’re hoping that what’s being done will turn this around, and things will start to improve… we’re hoping for the same thing, and doing everything we can to make that happen. Many people in such situations find that although they are hoping for a good outcome, at times their mind wanders to some scary ‘what-if’ thoughts, such as what if the treatments don’t have the effect that we hoped? Is this something you’ve experienced? Can we talk about that now?” “If Your Child Could Tell Us…” • when an older child is dying but too ill to participate in discussions, parents may have a sense of how that child would guide care if he/she could • rather than asking family what they would want done for their child, consider asking what their child would want • This off-loads family of a very difficult responsibility, by placing the ownership of the decision where it should be… with the patient. • The family is the messenger of the patient’s wishes, through their intimate knowledge of him/her Example… “If he could come to the bedside as healthy as he was a month ago, and look at the situation for himself now, what would he tell us to do?” Or “If you had in your pocket a note from him telling you that to do under these circumstances, what would it say?” Life and Death Decisions? when asked about common end-of-life choices, parents may feel as though they are being asked to decide whether their child lives or dies It may help to remind them that the underlying illness itself is not survivable… no decision can change that… “I know that you’re being asked to make some very difficult choices about care, and it must feel that you’re having to make life-anddeath decisions. You must remember that this is not a survivable condition, and none of the choices that you make can change that outcome. We know that his life is on a path towards dying… we are asking for guidance to help us choose the smoothest path.” The three ACP levels are simply starting points for conversations about goals of care when a change occurs Comfort Medical Resuscitation Goal-Focused Approach To Decision Making Regarding effectiveness in achieving its goals, there are 3 main categories of potential interventions: 1. Those that will work: Essentially certain to be effective in achieving intended physiological goals (as determined by the health care team) or experiential goals (as determined by the patient) goals, and consistent with standard of medical care 2. Those that won’t work: Virtually certain to be ineffective in achieving intended physiological goals (such as CPR in the context of relentless and progressive multisystem failure) or experiential goals (such as helping someone feel stronger, more energetic), or inconsistent with standard of medical care 3. Those that might work (or might not): Uncertainty about the potential to achieve physiological goals, or the hoped-for goals are not physiological/clinical but are experiential Goal-Focused Approach To Decisions Goals unachievable, or inconsistent with standard of medical care • Discuss; explain that the intervention will not be offered or attempted. • If needed, provide a process for conflict resolution: Mediated discussion 2nd medical opinion Ethics consultation Transfer of care to a setting/providers willing to pursue the intervention Uncertainty RE: Outcome Consider therapeutic trial, with: 1. clearly-defined target outcomes 2. agreed-upon time frame 3. plan of action if ineffective Goals achievable and consistent with standard of medical care • Proceed if desired by patient or substitute decision maker Revisiting The Cases Case 1: 7 month old infant with severe anoxic brain injury, question about hydration Case 2: 18 yo female with CF Case 3: 17 yo with widely metastatic Ewing’s sarcoma Additional Reference Material Children’s Conceptions of Death Kenyon BL; Omega: Journal of Death and Dying 2001; 43(1) 63–91 The most widely studied components of the concept of death are: 1. Non-functionality: the understanding that all life-sustaining functions cease with death 2. Irreversibility: the understanding that death is final and, once dead, a person cannot become alive again 3. Universality: understanding that death is inevitable to living things and that all living things die 4. Causality: refers to understanding what causes death 5. Personal mortality: related to universality but reflective of the deeper understanding not only that all living things die, but that “I will die.” (sometimes referred to in different terms (e.g., cessation for nonfunctionality, inevitability for universality) Children’s Conceptions of Death Kenyon BL; Omega: Journal of Death and Dying 2001; 43(1) 63–91 In general, it appears that universality followed by irreversibility emerge relatively early, with non-functionality and causality understood later children understand the cessation of external events (like movement) before internal events (such as thinking), after death Speece and Brent (1992) – studied children from kindergarten to 3rd grade: Non-functionality - difficult for children to master. 90 percent of the sample understood the cessation of motion only 65 percent of the sample understood that less obvious properties, like sentience (thinking, feeling) and perception (hearing, seeing) cease with death Children’s Conceptions of Death Kenyon BL; Omega: Journal of Death and Dying 2001; 43(1) 63–91 children understand death as a changed state by about 3 yo children understand that death is universal by about 5 – 6 yo; understand what causes death slightly later although an understanding of personal mortality has been demonstrated by children as young as 4 yo, it does not reliably emerge until 8 - 9 yo. current measures do not detect a complete understanding of universality, irreversibility, nonfunctionality, and personal mortality until about ten years of age Elements of Complete Developmental Understanding of Death Himelstein et al; NEJM 2004;350:1752-62 Concept of Death Questions Suggestive of Incomplete Understanding Implications of Incomplete Understanding Irreversibility (dead things will not live again) • How long do you stay dead? • When is my (dead pet) coming back? • Can I "un-dead" someone? • Can you get alive again when you are dead? Prevents detachment of personal ties, the first step in mourning Finality or nonfunctionality (all life-defining functions end at death) • What do you do when you are dead? • Can you see when you are dead? • How do you eat underground? • Do dead people get sad? Preoccupation with the potential for physical suffering of the dead person Universality (all living things die) • Does everyone die? • Do children die? • Do I have to die? • When will I die? • May view death as punishment for actions or thoughts of child or the dead person • May lead to guilt and shame • Why do people die? • Do people die because they are bad? • Why did my (pet) die? • Can I wish someone dead? May cause excessive guilt Causality (realistic understanding of the causes of death) Development of Death Concepts and Spirituality in Children Himelstein et al; NEJM 2004;350:1752-62 Predominant Concepts of Death Spiritual Development Interventions 0–2 yr • Has sensory and motor relationship with environment • Has limited language skills • Achieves object permanence • May sense that something is wrong None • Faith reflects trust and hope in others • Need for sense of selfworth and love • Provide maximal physical comfort, familiar persons and transitional objects (favorite toys), and consistency • Use simple physical communication >2 – 6 yr • Uses magical and animistic thinking • Is egocentric • Thinking is irreversible • Engages in symbolic play • Developing language skills • Believes death is temporary and reversible, like sleep • Does not personalize death • Believes death can be caused by thoughts • Faith is magical and imaginative • Participation in ritual becomes important • Need for courage • Minimize separation from parents • Correct perceptions of illness as punishment • Evaluate for sense of guilt and assuage if present • Use precise language (dying, dead) Age Range Characteristics Development of Death Concepts and Spirituality in Children Himelstein et al; NEJM 2004;350:1752-62 …ctd Age Range Characteristics Predominant Concepts of Death >6 – 12 yr Has concrete thoughts • Development of adult concepts of death • Understands that death can be personal • Interested in physiology and details of death • Faith concerns right and wrong • May accept external interpretations as the truth • Connects ritual with personal identity • Evaluate child’s fears of abandonment • Be truthful • Provide concrete details if requested • Support child's efforts to achieve control and mastery • Maintain access to peers • Allow child to participate in decision making >12 – 18 yr • Generality of thinking • Reality becomes objective • Capable of selfreflection • Body image and selfesteem paramount Explores nonphysical explanations of death • Begins to accept internal interpretations as the truth • Evolution of relationship with God or higher power • Searches for meaning, purpose, hope, and value of life • Reinforce child's self-esteem • Allow child to express strong feelings • Allow child privacy • Promote child's independence • Promote access to peers • Be truthful • Allow child to participate in decision making Spiritual Development Interventions