D6-Antibacterials

advertisement

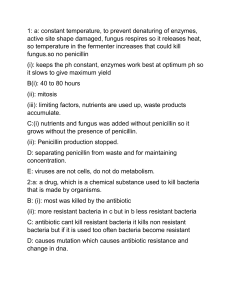

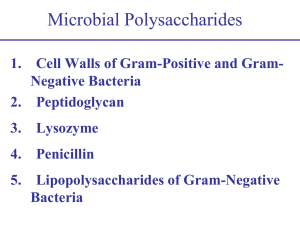

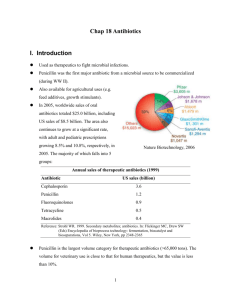

In 1928, Alexander Fleming was working with cultures of Staphylococcus aureus, a bacterium that causes boils and other types of infections. He accidently left open one of the petri dishes (ooops!) He later found mold growing, but no bacteria around the mold. He concluded that the mold (Penicillium notatum) inhibited growth of bacteria, but he could not isolate and purify it. In 1941, Ernst Chain and Howard Florey were able to isolate the fungus and test it with mice which were injected with a deadly bacteria. The mice treated with penicillin survived. After testing it on a policeman with an infection, the mass development of penicillin began in the U.S. Thousands of troops during WWII survived infections caused by wounds due to the penicillin. Bacteria have cell walls which eukaryotic cells do not. The cell walls are created by cross-linking of peptidoglycan. Penicillin G interferes with the enzyme that creates these cross-links. The cell wall weakens, causing the bacteria to burst (lyse) easily due to osmotic pressure. Modifying the Side Chain Penicillin G is deactivated by stomach acid, but can resistant to acid by modifying the side chain. Bacteria can also become resistant to penicillin by building enzymes which deactivate the penicillin (pencillinase) or having a modified enzyme for building the cell wall which does not allow the penicillin to bind to it. Modifying the side chain can sometimes overcome these types of resistance. Antibacterials can wipe out helpful bacteria (especially in the gastrointestinal system). Because of overprescription and use in animal feedstock, some bacteria have evolved to become extremely resistant to penicillin. With drug-resistant bacteria, a “cocktail” of different antibacterials are used to overcome the infection.