Chapter 9 - BU Blogs

advertisement

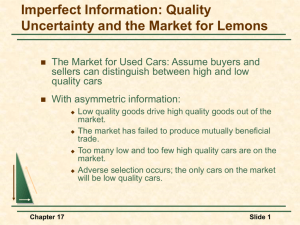

Economics 387 Lecture 9 Asymmetric Information and Agency Tianxu Chen Outline • Overview of Information Issues • Asymmetric Information • Application of the Lemons Principle: Health Insurance • The Agency Relationship • Consumer Information, Prices, and Quality • Conclusions OVERVIEW OF INFORMATION ISSUES Overview of Information Issues • Adverse selection, a phenomenon in which insurance attracts patients who are likely to use services at a higher than average rate, results from asymmetric information because potential beneficiaries have better information than the insurer about their health status and their expected demand for health care. • The possible preference for health care delivery by nonprofit hospitals and nursing homes has been attributed to patients’ lack of information and inability to discern quality. For some patients, a nonprofit status might be taken as reassurance of higher quality because decisions are made independent of a profit motive. Goals for this Chapter • Introduce information asymmetry, describe its relative prevalence, and determine its consequences, especially for insurance markets. • Describe the agency relationship and examine some of the problems arising in health care markets from imperfect agency. • Examine the effects of imperfect consumer information on the price and quality of health care services. ASYMMETRIC INFORMATION On the Extent of Information Problems in the Health Sector • Certainly information gaps and asymmetries exist in the health sector. They are perhaps more serious for health care than for other goods that are important in household budgets. • However, one should not assert that information gaps preclude the possibility of having a high degree of competition. In particular, mechanisms to deal with information gaps should not be overlooked. These mechanisms include licensure, certification, accreditation, threat of malpractice suits, the physician-patient relationship, ethical constraints, and the presence of informed consumers. Asymmetric Information in the Used-Car Market – The Lemons Principle • Nobel Laureate George Akerlof (1970) is often credited with introducing the idea of asymmetric information through an analysis of the used-car market. • First, it tells us much about adverse selection and the potential unraveling of health insurance markets. • Second, Akerlof’s example leads right into the issue of agency. the Used-Car Market – The Lemons Principle • Nine used cars to be sold that vary in quality from 0 (a lemon) to 2 (a mint-condition used car). The nine cars have respectively quality levels Q given by the cardinally measured index values of 0,1/4,1/2,3/4,1,5/4,3/2,7/4 and 2. • The reserve value to the seller=$5000*Q; • The reserve value to the nonowners=$7500*Q, because they are more eager for used card and value them. • Asymmetic information: onowners know only the distribution of quality but not the quality of each individual car, will make a best guess that a given car is of average quality, that is Q=1. • The auctioneer calls out an initial price of $10000. Fail? • Now try a price at $7500, the best car quality offered is 3/2, average quality will be ¾. Only willing to pay $5625. Fail? Figure 10-1 The Availability of Products of Different Quality (Uniform Probability of Picking Each Car) The Lemons Principle • When potential buyers know only the average quality of used cars, then market prices will tend to be lower than the true value of the top-quality cars. Owners of the top-quality cars will tend to withhold their cars from sale. In a sense, the good cars are driven out of the market by the lemons. Under what has become known as the Lemons Principle, the bad drives out the good until no market is left. The Lemons Principle • Now try imperfect versus asymmetric information: • Both owners and nonowners were uncertain of the quality, that they knew only the average quality of used cars on the market. • The auctioneer calls out an initial price of $10000. Fail? • Now try a price at $7500? • The market exists, and clears (supply equals demand) if the information is symmetric- in this case, equally bad on both sides. APPLICATION OF THE LEMONS PRINCIPLE: HEALTH INSURANCE Overview • Adverse selection applies to markets involving health insurance and to analyses of the relative merits of alternative health care provider arrangements. • Information asymmetry will likely occur because the potential insureds know more about their expected health expenditures in the coming period than does the insurance company. • In this market, the higher health risks tend to drive out the lower health risk people, and a functioning market may even fail to appear at all for some otherwise-insurable health care risks. Figure 10-2 Uniform Probability of Expenditure (Expected Health Expenditure Levels) APPLICATION OF THE LEMONS PRINCIPLE: HEALTH INSURANCE • The auctioneer attempts a first trial price to $0 M? • Now try $1/2 M? • The remaing insured persons with expected expenditures $¾ M. • Market fail. Inefficiencies of Adverse Selection • If the lower risks are grouped with higher risks and all pay the same premium, the lower risks face an unfavorable rate and will tend to underinsure. They sustain a welfare loss by not being able to purchase insurance at rates appropriate to their risk. Conversely, the higher risks will face a favorable premium and therefore over-insure; that is, they will insure against risks that they would not otherwise insure against. This, too, is inefficient. Evidence of Adverse Selection • Evidence of adverse selection has been found in markets for supplemental Medicare insurance (Wolfe and Goddeeris, 1991) and individual (nongroup) insurance (Browne and Doerpinghaus, 1993). • Cardon and Hendel (2001) found that those who were insured spent about 50 percent more on health care than the uninsured. Experience Rating and Adverse Selection • Group insurance can be a more useful mechanism to reduce adverse selection. • Group plans enable insurers to implement experience rating, a practice where premiums are based on the past experience of the group, or other risk-rating systems to project expenditures. Because employees usually have limited choices both within and among plans, they cannot fully capitalize on their information advantage. THE AGENCY RELATIONSHIP What is the Agency Relationship? • An agency relationship is formed whenever a principal (for example, a patient) elegates decisionmaking authority to another party, the agent. • In the physician-patient relationship, the patient (principal) delegates authority to the physician (agent), who in many cases also will be the provider of the recommended services. Agency and Health Care • The perfect agent physician is one who chooses as the patients themselves would choose if only the patients possessed the information that the physician does. • The problem for the principal is to determine and ensure that the agent is acting in the principal’s best interests. Unfortunately, the interests may diverge, and it may be difficult to introduce arrangements or contracts that eliminate conflicts of interest. CONSUMER INFORMATION, PRICES AND QUALITY Overview • Would relatively poor consumer information reduce the competitiveness of markets? • Does increasing physician availability increase competition and lower prices as traditional economics suggests? • What happens to quality? • How do consumers obtain and use information? Consumer Information and Prices • Satterthwaite (1979) and Pauly and Satterthwaite (1981) introduced one of the most novel approaches to handle issues involving consumer information and competition. • The authors identify primary medical care as a reputation good—a good for which consumers rely on the information provided by friends, neighbors, and others to select from the various services available in the market. • Physicians are not identical and do not offer identical services. • Because of this product differentiation, the market can be characterized as monopolistically competitive. Reputation Goods • Under these conditions, the authors show that an increase in the number of providers can increase prices. • The economic idea is that reduced information tends to give each firm some additional monopoly power. The Role of Informed Buyers • The degree to which imperfect price information contributes to monopoly power should not be overemphasized. • A growing body of literature shows that it is sufficient to have enough buyers who are sensitive to price differentials to exert discipline over the marketplace. Price Dispersion • Nobel Laureate George Stigler (1961) argued that variation in prices will increase under conditions of imperfect consumer information. • Gaynor and Polachek (1994) found that both patients and physicians exhibited incomplete information with the measure of ignorance being one and one-half times larger for patients than for physicians. Consumer Information and Quality • Consider the consumer’s direct role through the Dranove and White argument that the physician– patient relationship enables patients to monitor providers and encourages physicians to make appropriate referrals. • To the extent that many specialists rely on referred patients, these specialists would seem to have incentives to maintain quality. Are they also rewarded with higher prices for higher-quality services? Haas-Wilson study • To the extent that many specialists rely on referred patients, these specialists would seem to have incentives to maintain quality. Are they also rewarded with higher prices for higher-quality services? • The evidence shows that patients rely on informed sources (agents) for information and that higher quality, as measured by informed referrals, is rewarded by higher fees. Other Quality Indicators • The National Committee for Quality Assurance (NCQA), a private accreditation body for HMOs, issues report cards based on about 50 standardized measures of a plan’s performance (such as childhood immunization rates, breast cancer screening, and asthma inpatient admission rates). • A key assumption behind efforts like this is that information about quality will, like price information, help discipline providers through patient choices. Evidence • Initial evidence on the intended effects of plan performance ratings brings the report card strategy into question. Tumlinson et al. (1997) found that independent plan ratings are relatively unimportant to consumer choices. • Chernew and Scanlon (1998), employing multivariate statistical methods on consumer choice of plans, confirm that “employees do not appear to respond strongly to plan performance measures, even when the labeling and dissemination were intended to facilitate their use” (p. 19). More Evidence • In subsequent work, Scanlon and colleagues (2002) examined a flexible benefits system introduced by General Motors in 1996 and 1997 and found that plans with many above-average ratings were not much more successful in attracting enrollees relative to plans with many average ratings. • Together with other results on plan switching (Beaulieu, 2002), we can conclude that the provision of quality information does influence consumers, particularly when the quality ratings are negative. CONCLUSIONS • There is little doubt that information gaps, asymmetric information, and agency problems are prevalent in provider–patient transactions. • Although there is a potential lack of competition, even wide information gaps do not necessarily lead to market failure.