Best Interests in Paediatrics

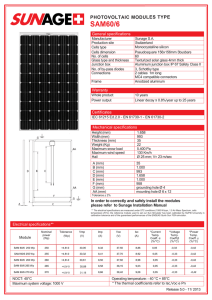

advertisement

“Best Interests” in Paediatrics Zoe Picton-Howell, Solicitor (Hons) (England & Wales) PhD Researcher, School of Law, University of Edinburgh S Zoe Picton-Howell Z.Picton-Howell@sms.ed.ac.uk PhD Researcher, School of Law, University of Edinburgh: “What do law, rights and ethics bring to difficult clinical decisions made by doctors when treating children with disabilities”? Solicitor (Hons) (England & Wales) LLM Human Rights Law (Glasgow) LLB (Hons) (London) BA (Hons) English Author of Medical Care for Children, Law, Rights & Ethics (on-line, Edinburgh University) Lay Member, RCPCH Expert Group on Epilepsy for UK-Child Health Review as part of UK Clinical Outcomes Review Programme Parent Advisor to RCPCH Member of Scottish Government/NHS Advisory Group on staff training for Carers’ Strategy Member of National Clinical Network for Children with Exceptional Health Care Needs Director/Treasurer, Together, Scottish Alliance for Children’s Rights KEY ELEMENTS OF THE “BEST INTERESTS” TEST • Article 3, United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child:“In all actions concerning children, the best interests of the child shall be a primary consideration.” • “the golden thread” which runs “throughout the tangled web of English Family Law” Lord St John Fawley, House of Lords Debate 31/01/2007 • Phrase “Best Interests” used in 322 pieces of UK legislation. • Central to General Medical Council & Nursing & Midwifery Council codes of professional conducthttp://www.gmcuk.org/guidance/ethical_guidance/children_guidance_12_13_assessing_best_i nterest.asp • http://www.nmc-uk.org/Nurses-and-midwives/Standards-and-guidance1/Thecode/The-code-in-full/ WHAT IS THE TEST? “ Best Interests” Decision:“a welfare appraisal in the widest sense, taking into account, where appropriate, a wide range of ethical, social, moral, emotional and welfare considerations” Burke, R (on the application of) v The General Medical Council Rev 1 [2004] EWHC 1879 (Admin) (30 July 2004); per Munby J, para 90 HOW SHOULD THE TEST BE MADE? “the judge must look at the question from the assumed point of view of the patient” Re J (A Minor) (Wardship: Medical Treatment) [1991] : 2 WLR 140 “best interests encompasses medical, emotional and all other welfare issues” Re A (Male Sterlisation) [2000] 1 FLR 549 “there is a strong presumption in favour of a course of action which will prolong life, but that presumption is not irrebuttable”. Re J (A Minor) “The Court must conduct a balancing exercise in which all the relevant facts are weighed” Re J (A Minor) “and a helpful way to undertake this exercise is to draw up a balance sheet” Re A (Male Sterilisation) [2000] 1 FLR 549, at para 87 CHILD SPECIFIC ISSUES:• Age specific compentence: http://www.gmc-uk.org/guidance/ethical_guidance/ children_guidance_24_26_assessing_capacity.asp • Conflicts between medical staff and parents and or conflicts between parents:Wyatt & Anor v Portsmouth Hospital NHS & Anor [2005] EWCA Civ 1181 (12 October 2005) A NHS Trust v MB [2006] EWHC 507 (Fam) Re T (A Minor) Wardship: Medical Treatment [1997]: 1 WLR 242 • Balancing competing best interests of two children:Re A (Children) (Conjoined Twins: Surgical Separation) [2001] 2 WLR 480, [2000] 4 All ER 961, [2001] Crim LR 400, [2001] Fam 147 • Conflict between a young person (under 16) and their parent as to what is in the young person’s best interests. CHILD SPECIFIC ISSUES (2) • Children with disabilities Wyatt & Anor v Portsmouth Hospitals NHS & Anor [2005] EWCA Civ 1181 (12 October 2005) Glass v United Kingdom 61627/00 [2004] ECHR 103 (9 March 2004) Ability to make a prognosis for individual child; Ability to accurately assess child’s quality of life from the view point of the child; Ability to accurately assess competence of child to take part in the decision making process; Ability to communicate with the child. Should Sam have a flu jab? Sam is 12 years old. He has exceptionally complex health problems. He has severe cerebral palsy. He is only able to move his head. He communicates by blinking. He has a tracheotomy (an airway through his trachea) and requires oxygen constantly. He has repeated and prolonged hospital admissions, including admissions to high dependency and intensive care and at times, when particularly unwell requires ventilation support. He has spent more of his life in hospital than out. He has chronic respiratory illness and frequent acute respiratory illness. He has intractable seizures (epilepsy which can not be controlled using medication). He has growth failure. Sam is immunosuppressed. He has automonic dysfunction, which means he cannot regulate his temperature, so frequently becomes hypothermic; cannot sweat and is prone to stopping breathing. Sam also has metabolic and endocrine health conditions. Sam has had flu on two previous occasions. On both occasions Sam become critically ill. On both occasions once he recovered from flu, Sam had sustained permanent damage to his lungs. Sam has had the flu jab on three previous occasions. On each occasion, because of Sam’s complex health problems this has been given in the hospital. On the first occasion Sam had facial and mouth swelling immediately on having the jab. On the second occasion Sam did not have an adverse reaction. On the third occasion, Sam had facial and mouth swelling. His oxygen saturations (the amount of oxygen circulating in his body) dropped meaning he required high flow oxygen. He was transferred to the resuss room. He received antihistamines and steroids and after being observed for two hours was discharged home. Sam has a history of severe reactions to numerous medicines, including on occasions reactions so severe that he has stopped breathing. His reactions have been reviewed by specialists in two tertiary specialist children’s hospitals locally, as well as at Great Ormond Street Hospital and St. Thomas’ (London). St. Thomas’ is the UK’s centre of excellence for allergies. Doctors all agree that Sam reacts to medication, but they are unclear of the medical reason as it is not a classic “allergic reaction”. When well, Sam is a bright and happy boy. He attends mainstream school supported by a nurse and a teaching assistant. He is at the top end of the ability range for his age. Sam has a particular talent for writing, which he does by blinking out the words and phrases. He has won numerous awards for writing. He receives glowing school reports. In his most recent school test he obtained 82%. Sam is very popular with his classmates. According to his teacher he is the most popular boy in the class. He also has a wide circle of friends outside of school. He loves literature, especially Michael Mopurgo; music; science; watching sport; history and quizzes. He also loves fundraising for charities, which support sick and disabled children and raised over £10,000 last year. When well he lives at home with his mum, dad, cousin and pet dog. Sam is treated by a wide team of paediatric consultants in a number of specialist children’s hospitals and they are unable to agree whether it is in Sam’s best interests to have the flu jab this year. The doctors all agree that: Sam is at very high risk of catching flu; If Sam catches flu he will definitely become critically ill; There is a very high risk that flu would be fatal to Sam; Sam has concerning reactions to the flu jab; The exact nature of these reactions are unknown. There is disagreement between the doctors as to: Whether or not the flu jab is potential fatal to Sam; Whether or not in the event of an adverse reaction to the flu jab, with ITU support doctors would be able to reverse the reaction; Whether or not it is in Sam’s best interests to have the flu jab. What do you think? Is it in Sam’s best interests to have the flu jab? How & by whom should this decision be made? How have you made your decision? SUGGESTED READING:Cases Airedale NHS Trust v Bland, (1993) 2WLR 316; A NHS trust v MB [2006], EWHC 507 (Fam); Burke, R (on the application of ) v The General Medical Council Rev 1 [2004] EWHC 1879(Admin) (30 July 2004); per Munby J, para 90; Glass, R (on the application of) v Portsmouth Hospitals NHS Trust [1999] EWCA Civ 1914 (21 July 1999) Glass v United Kingdom, 61627/00 [2004] ECHR 103 (9 March 2004) ; Portsmouth NHS Trust v Wyatt & Ors [2004] EWHC 2247 (Fam) (7 October 2004; R v Portsmouth Hospitals NHS Trust Ex P. G [1999] 2FLR 905; Re C (A Minor) (Medical Treatment) [1998], 1FLR 384; Re A (Male Sterilisation) [2000] 1 FLR 549; Re J ( A Minor) (Wardship: Medical Treatment) [1991]; 2 WLR 140; Re L (A Child) (Medical Treatment: Benefits) [2004] EHHC 2713 (Fam) Re T ( A Minor) Wardship: Medical Treatment) [1997]; 1 WLR 242; Wyatt & Anor v Portsmouth Hospital NHS & Anor [2005] EWCA Civ 1181 (12 October 2005); Statutes & Conventions Article 2, The European Convention for the Protection of Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms, 1950 ("ECHR") and Article 6, United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child, 1989 ("UNCRC"); Article 6, United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child, 1989 ("UNCRC"); Children (Scotland) Act 1995; The Children Act 1989; Journals Gething,L Judgements (sic) By Health Professionals of Personal Characteristics Of People With A Visible Physical Disability (1992) 34, Social Science and Medicine 809 at 812 Huxtable, Forbes; Glass v UK: Maternal Instinct v Medical Opinion; Child and Family Law Quarterly, vol.16, No.3, 2004, pp339-354 Irvine, Donald H., Everyone’s Entitled to A Good Doctor, MJA, vol. 186; no.5, 5/3/07; Medical, Law Review, Withdrawal of Life Sustaining Treatment for Child Without Parental Consent: R v Portsmouth Hospitals NHS Trust ex parte Glass. Medical Law Review , 125-129. (2000; Paris M.J., Attitudes of Medical Students & Healthcare Professionals towards people with Disabilities, Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, 818, 1993; Books Brazier , Margaret and Cave, Emma, Medicine, Patients and the Law, Penguin Books; Elliston, Sarah; “The Best Interests of the Child In Healthcare”; Biomedical Law and Ethics Library; Routledge Cavendish; 2007; Lantos, John D & Meadows, William; “Neonatal Bioethics: the moral challenges of medical innovation;” The Johns Hopkins University Press; 1st edition. 2006; MacClean; The Human Rights Act 1998 and the Individual’s Right to Treatment; Medical Law International 2000, vol 4; pp 245-276; Mason, JK & Laurie, GT; “Mason & McCall Smith’s Law and Medical Ethics”; Seventh Edition; Oxford University Press; 2006; McLean, S. From Bland to Burke: The Law and Politics of Assisted Nutrition & Hydration. In McLean, S First Do No Harm (pp. 421-446). Aldershot: Ashgate, 2006; Guidance General Medical Council; 0-18 guidance for all doctors: http://www.gmcuk.org/guidance/ethical_guidance/children_guidance_index.asp Nursing & Midwifery Council: Code; http://www.nmc-uk.org/Nurses-andmidwives/Standards-and-guidance1/The-code/The-code-in-full/ Nuffield Council in Bioethics, “Critical care decisions in foetal and neonatal medicine: ethical issues”; Nuffield Council on Bioethics, November 2006 Office of the High Commissioner For Human Rights, General Comment No.5 (2003), General measures of implementation of the Convention on the Rights of the Child (arts.4, 42 and 44, para 6), CRC/GC/2003/5 , 27/11/2003; Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health, Withholding or Withdrawing Life Sustaining Treatment in Children, A Framework for Practice, second edition, May 2004