File - Respiratory Therapy Files

advertisement

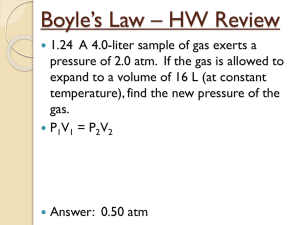

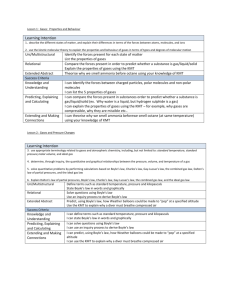

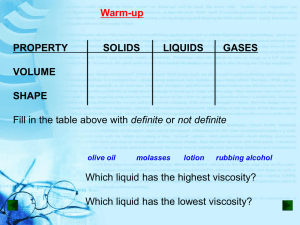

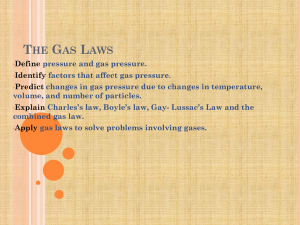

Physical Principles of Respiratory Care Egan Chapter 6 Physical Principles of Respiratory Care I. II. III. IV. States of Matter Change of State Gas Behavior Under Changing Conditions Fluid Dynamics III. Gas Behavior Under Changing Conditions A. Gas Laws 1. Effect of Water Vapor Corrected Pressure Computations Correction Factors 2. Properties of Gases at Extremes of Temperature and Pressure 3. Critical Temperature and Pressure A. Gas Laws Boyle’s Law Charles’ Law Gay-Lussac’s Law Boyle’s Law Robert Boyle 1627-1691 British chemist Pressure-volume relationship 5 Boyle’s Law 6 If temperature (T) remains constant, pressure (P) will vary inversely to volume (V) P1V1 = P2V2 Boyle’s Law If temperature (T) remains constant, pressure (P) will vary inversely to volume (V) If gas P , the V occupied by the gas If gas V , the P exerted by the gas 7 Boyle’s Law P 8 T V Ventilation is an example of Boyle’s Law As the diaphragm drops at the beginning of inspiration The volume of the lungs increases As lung volume increases what happens to the pressure inside the lungs? It _________ And air flows into the lungs http://www.youtube.com/watch? v=q6-oyxnkZC0 9 Boyle’s Law A snorkel diver is preparing to descend a freshwater pond to a depth of 66 feet. At sea level, his lungs contain about 3000 mL of air. As he descends below the surface of the water, what will happen to the gas volume in his lungs as he descends to 66 feet below the surface of the pond? 10 Charles’ Law Jacques Charles 1746-1823 French chemist Volumetemperature relationship 11 Charles’ Law 12 If pressure (P) remains constant, the volume (V) will vary directly with temperature (T) V1 = V2 T1 T2 Charles’ Law If pressure (P) remains constant, the volume (V) will vary directly with temperature (T) If gas T , the V occupied by the gas also If gas T , the V occupied by the gas also 13 As T , kinetic energy , the gas molecules move more vigorously and the gas expands As T , kinetic energy , the gas molecules slow down and the gas contracts Tire volume is an example of Charles’ Law 14 Gay-Lussac’s Law An oxygen cylinder has a pressure of 2200 psi at a temperature of 25 C, what will its pressure be if it is heated to 50 C? (Must first convert temperature to Kelvin) 15 Gay-Lussac’s Law Joseph Gay-Lussac 1778-1850 Expanded on Charles’ work Pressure-temperature relationship 16 Gay-Lussac’s Law 17 If volume (V) remains constant, pressure (P) will vary directly with temperature (T) P1 = P2 T1 T2 Gay-Lussac’s Law If volume (V) remains constant, pressure (P) will vary directly with temperature (T) If gas T , the P exerted by the gas also If gas T , the P exerted by the gas also 18 Gas Cylinder Pressures and Temp is an example of Gay-Lussac’s Law An alarm signals that there is a fire in the basement of the hospital. Although the fire is confined to an area that is approximately 300 feet from the room where the compressedgas cylinders are stored, you are asked to move the cylinders to a safer location. Why is it necessary to move the cylinders? Keep cylinder temperature below 125°F (51.7°C) http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xceBXe5YH j0 19 Charles’ Law Given: 100 mL of an unknown gas measured at 28° C and 760 mmHg. Find the gas volume measured at 37° C and 760 mmHg.(Must first convert temperature to Kelvin) 20 III. Gas Behavior Under Changing Conditions A. Gas Laws 1. Effect of Water Vapor In clinical practice, most gas law calculations must take into account the presence of water vapor. Water vapor, similar to any gas, occupies space. The dry volume of a gas at a constant pressure and temperature is always smaller than its saturated volume. The opposite is also true. Correcting from the dry state to the saturated state always yields a larger gas volume. The addition of water vapor to a gas mixture always lowers the partial pressures of the other gases present. This fact becomes relevant when discussing the partial pressure of gases in the lung where the gases are saturated with water vapor at body temperature. III. Gas Behavior Under Changing Conditions A. Gas Laws 1. Effect of Water Vapor The addition of water vapor to a gas mixture always lowers the partial pressures of the other gases present. This fact becomes relevant when discussing the partial pressure of gases in the lung where the gases are saturated with water vapor at body temperature. III. Gas Behavior Under Changing Conditions A. Gas Laws 1. Effect of Water Vapor Corrected Pressure Computations PC = (PT – PH 0) 2 III. Gas Behavior Under Changing Conditions A. Gas Laws 1. Effect of Water Vapor Correction Factors Correction from ATPS to BTPS Correction from ATPS to STPD Correction from STPD to BTPS Table 6-3 Clinical Example: Spirometry Spirometry: laboratory evaluation of lung function using a spirometer Spirometer: a device for measuring lung volumes and/or flows When a patient exhales into a spirometer the gas is measured at room temperature About 25°C ATPS: Ambient Temperature Pressure Saturated But inside the lungs the gas is at body temperature 26 About 37°C BTPS: Body Temperature Pressure Saturated Clinical Example: Spirometry As the patient exhales and the temperature of the gas decreases to room temperature What will happen to the volume of gas? Whose law tells us this? 27 III. Gas Behavior Under Changing Conditions A. Gas Laws 1. Properties of Gases at Extremes of Temperature and Pressure See Mini Clini: Variations from Ideal Gas Behavior: Expansion Cooling and Adiabatic Compression page 121. III. Gas Behavior Under Changing Conditions A. Gas Laws 2. Critical Temperature and Pressure Critical temperature: the highest temperature at which a substance can exist as a liquid. The temperature above which the kinetic activity of its molecules is so great that the attractive forces cannot keep them in a liquid state. Critical pressure: the pressure needed to maintain equilibrium between the liquid and gas phases of a substance at this critical temperature. Together, the critical temperature and pressure represent the critical point of a substance. 2. Critical Temperature and Pressure Liquid oxygen is produced by separating it from a liquefied air mixture at a temperature below its boiling point (−183° C or −297° F). After it is separated from air, the oxygen must be maintained as a liquid by being stored in insulated containers below its boiling point (-183 ° C) If higher temperatures are needed, higher pressures must be used. If at any time the liquid oxygen exceeds its critical temperature of −118.8° C, it converts immediately to a gas.