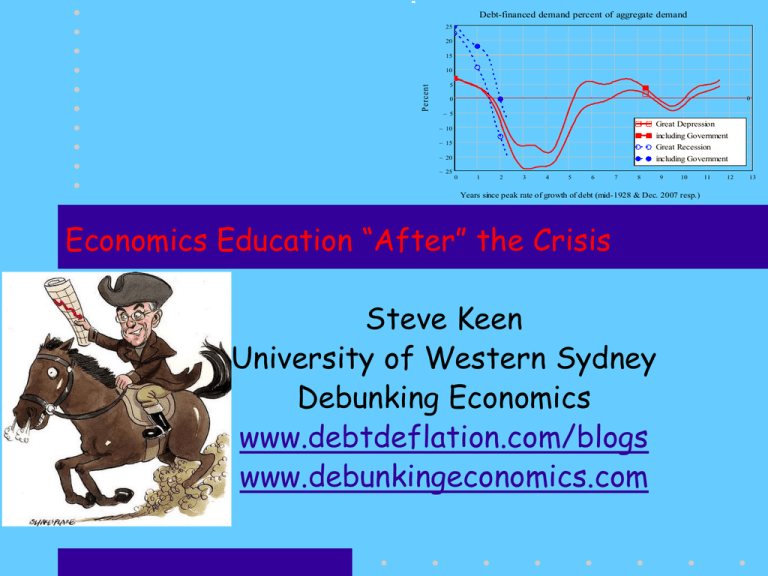

Misunderstanding the Great Depression, making the

advertisement

Debt-financed demand percent of aggregate demand 25 20 15 P ercent 10 5 0 0 5 Great Depression 10 15 including Government Great Recession 20 including Government 25 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Years since peak rate of growth of debt (mid-1928 & Dec. 2007 resp.) Economics Education “After” the Crisis Steve Keen University of Western Sydney Debunking Economics www.debtdeflation.com/blogs www.debunkingeconomics.com 11 12 13 Before the Crisis • Oliver Blanchard, founding editor of AER Macro – “The state of macro is good…” – “Dynamic Stochastic General Equilibrium” model is… – “simple, analytically convenient, and has largely replaced the IS-LM model as the basic model of fluctuations in graduate courses…” – “Unlike the IS-LM model, it is formally, rather than informally, derived from optimization by firms and consumers.” (Blanchard 2009, pp.214-215) “After” the crisis… • “The great moderation lulled macroeconomists and policymakers alike in the belief that we knew how to conduct macroeconomic policy. • The crisis clearly forces us to question that assessment… • It is important to start by stating the obvious, namely, that the baby should not be thrown out with the bathwater…” (Blanchard Dell'Ariccia et al. 2010; emphasis added) • Wrong: this baby should never have been conceived – DSGE models logically flawed – Deep neoclassical research proved cannot reduce macro to applied micro before DSGE models developed • Why don’t neoclassical economists know this? A paradoxical but transcendental truth… • Learn theory from textbooks: Mankiw, Varian, Mas-Colell – Ignore fundamental research in good faith • Should be able to trust textbooks to truthfully summarize fundamental research – But textbooks teach sanitized “as if” version of theory • Macro “as if” can model whole economy as one agent – Fundamental research: “as if” conditions false • Consequently: – Neoclassical economists don’t understand neoclassical economics; and – Neoclassical models violate neoclassical theory • Illustration: DSGE models, SMD conditions, & Solow Solow rejects DSGE • Solow (2001 p. 19; emphases added) – “The prototypical real-business-cycle model goes like this. There is a single, immortal household—a representative consumer—that earns wages from supplying labor. It also owns the single price-taking firm… – This is nothing but the neoclassical growth model… – [When I built it] … It was clear … what I thought it did not apply to, namely short-run fluctuations ... the business cycle... – Now ... an article today [on the] 'business cycle' … will be ... a slightly dressed up version of the neoclassical growth model. – The question I want to circle around is: how did that happen?” Solow: SMD conditions invalidate DSGE • “Suppose you wanted to defend the use of the Ramsey model as the basis for a descriptive macroeconomics. What could you say? ... • You could claim that … there is no other tractable way to meet the claims of economic theory. • I think this claim is a delusion. • We know from the Sonnenschein-Mantel-Debreu theorems that the only universal empirical aggregative implications of general equilibrium theory are that excess demand functions should be continuous and homogeneous of degree zero in prices, and should satisfy Walras' Law. • Anyone is free to impose further restrictions on a macro model, but they have to be justified for their own sweet sake, not as being required by the principles of economic theory.…” (Solow 2008, p. 244; emphasis added) Sonnenschein-Mantel-Debreu Conditions • “Law of Demand” applies to individual Hicksiancompensated demand curve – Reduce price, demand necessarily rises • Does it apply to a market demand curve? No!: • “we prove that every polynomial … is an excess demand function for a specified commodity in some n commodity economy… (Sonnenschein 1972 , pp. 549-550) – That is, a demand curve for a single market can have any (polynomial) shape at all • Even study of a single market demand curve can’t be reduced to study of a demand curve derived from a single utility-maximizing agent • Yet Neoclassical DSGE macro models the whole economy as a single utility/profit-maximizing agent SMD: “Anything goes” for market demand curves • SMD Conditions (Sonnenschein 1973; Shafer & Sonnenschein 1993;): – Market demand curves do not obey the "Law of Demand" – Even if summing "well behaved" individual demand curves P Crusoe P Friday q P q Market Q • An accidental "Proof by contradiction": – Assume market demand curves do obey Law of Demand – Derive conditions under which this is true – These contradict initial assumptions • Therefore market demand curves don‘t obey the "Law" of Demand Logic: Price changes alter income distribution • Z X Coconuts B (1) Can vary Price without altering income • Pivot point does not move Y q1 q2 q3 II I III Bananas Price of Bananas • Logic: – “Law of Demand” derived from Hicksian compensated demand curve procedure – Take individual with well-behaved utility function – Vary price of one commodity while keeping others constant and consumer income constant • Key assumptions: p1 p2 p3 q1 q2 q3 Bananas W Individual demand curve derivation X Coconuts • (2) Can change income and perfectly compensate for income effect of lower price (Hicksiancompensation) • Outcome: Hicksian-compensated individual demand curve necessarily slopes down: the “Law of Demand” Price of Bananas • Motivation behind SMD research: Does this result survive aggregation to market demand? – Answer: No! q1 q2 q3 Bananas p1 p2 p3 q1 q2 q3 Bananas With more than one consumer… • Logic: “individual demand curve” model ignores impact of price changes on income – But price changes will change income distribution • In 2 (or more) consumer model, each must have – Different income sources; and – Different tastes • Otherwise, there’s only one consumer – Tastes must change with income • Otherwise, there’s only one commodity • Consider 2-consumer, 2 commodity world – Crusoe and Friday; Coconuts and Bananas – Crusoe the Banana owner, Friday Coconut owner – Coconuts necessity, Bananas luxury – Friday higher preference for coconuts than Crusoe Change in relative price alters incomes • Start with arbitrary price ratio; • Keep aggregate income constant; • Consider lower price for bananas – Crusoe’s (banana owner) income falls; Friday’s rises Coconuts Coconuts Crusoe Bananas Friday Bananas • Market demand for bananas falls because of lower price – Crusoe’s income fell – Friday’s income rose – But his preferences for bananas less than Crusoe’s Income growth alters distribution if tastes differ • Hicksian procedure – Keep relative prices constant – Increase income equally – Banana demand (luxury) rises more than Coconut – Crusoe’s income rises more than Friday’s Coconuts Coconuts Crusoe Bananas Friday Bananas • Cannot “compensate” for income effect of price change: – “Uniform” increase in income alters income distribution, because varying consumption as income rises favours luxury-producing agent over the other Market demand curve any polynomial at all • Outcome: market demand curve can have any (polynomial) shape at all – Need not obey “Law of Demand” • Only way to avoid this: – Assume all consumers have identical tastes • So there is only one consumer! – And assume that tastes don’t change with income • So there is only one commodity! • Contradicts starting assumption: – Two consumers with different tastes – Two different commodities • Proof by contradiction that “Law of Demand” does not apply to market demand curve • How is this communicated to students? Textbooks hide SMD results • Samuelson and Nordhaus 2010 (p. 48) – “The market demand curve is found by adding together the quantities demanded by all individuals at each price. – Does the market demand curve obey the law of downward-sloping demand? It certainly does…” • A provably false statement misleading undergraduates • Varian 1984 (p. 268) – “it is sometimes convenient to think of the aggregate demand as the demand of some ‘representative consumer’… – The conditions under which this can be done are rather stringent, but a discussion of this issue is beyond the scope of this book…” • A vague statement reassuring PhD students Macro an “emergent property” • Real meaning of SMD conditions – Macroeconomic behavior an “emergent property” of interaction of agents in a complex system • Cannot deduce behavior of macroeconomy from behavior of utility-maximizing individuals • Cannot reduce macroeconomics to “applied microeconomics” • But that is what DSGE models do! – Believe “macroeconomics is applied microeconomics” – But SMD conditions prove otherwise • “macroeconomics cannot be applied microeconomics” • Neoclassical theory commits the fallacy of “Strong Reductionism”… Fallacy of Strong Reductionism • Common knowledge in real sciences • Physics Nobel Laureate Anderson in “More is Different”, Science (1972, Vol. 177, p. 393) – “The behavior of large and complex aggregates of elementary particles, it turns out, is not to be understood in terms of a simple extrapolation of the properties of a few particles. – Instead, at each level of complexity entirely new properties appear, and the understanding of the new behaviors requires research which I think is as fundamental in its nature as any other.” Fallacy of Strong Reductionism • “one may array the sciences roughly linearly in a hierarchy, according to the idea: “The elementary entities of science X obey the laws of science Y” X Solid state or many-body physics Chemistry Molecular biology Cell biology … Psychology Social sciences Y Elementary particle physics Many-body physics Chemistry Molecular biology … Physiology Psychology • But this hierarchy does not imply that science X is “just applied Y”. At each stage entirely new laws, concepts, and generalizations are necessary, requiring inspiration and creativity to just as great a degree as in the previous one. Psychology is not applied biology, nor is biology applied chemistry.” Neoclassical macro didn’t see “It” coming • Strong reductionism blinded neoclassical macroeconomists: • “The preferred model has a single representative consumer optimizing over infinite time with perfect foresight or rational expectations, in an environment that realizes the resulting plans more or less flawlessly through perfectly competitive forward-looking markets for goods and labor, and perfectly flexible prices and wages. • How could anyone expect a sensible short-to-medium-run macroeconomics to come out of that set-up? … • we want macroeconomics to account for the occasional aggregative pathologies that beset modern capitalist economies, like recessions, intervals of stagnation, inflation, “stagflation”… • A model that rules out pathologies by definition is unlikely to help.” (Solow 2003, p. 1; emphases added) Many other flaws in neoclassical doctrine • Money is not neutral in a credit economy: – “nothing is so unimportant as the [nominal] quantity of money … let the number of dollars in existence be multiplied by 100; that … will have no other essential effect provided that all other nominal magnitudes (prices of goods and services, and quantities of other assets and liabilities that are expressed in nominal terms) are also multiplied by 100.” Friedman 1969 (p. 1) • Debts aren’t increased when prices rise – hence money is not neutral in a credit economy • Rational expectations = “capable of accurate prophesy” – Lucas 1972 (p. 54) “one is led simply to adding the assumption that [the gap between actual and expected inflation] is zero as an additional axiom… or to assume that expectations are rational in the sense of Muth.” • No wonder neoclassical macro couldn’t explain the crisis! Neoclassical macro can’t explain “It” continuing… • US Unemployment rising again after brief fall: USA Unemployment Rate 12 Start End 11 Percent of workforce 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 www.debtdeflation.com/blogs • Non-neoclassical macro can explain “It” and why “It” is continuing… • “We don't have a precise read on why this slower pace of growth is persisting” (Bernanke, June 23 2011) • The Economist: “His admission of ignorance reflects genuine puzzlement with the economy’s failure to 2012 reach what he likes to call escape velocity.” Private debt crisis, just like the Great Depression US Private Debt to GDP 275 12 10 8 2 4 6 6 4 2 0 8 10 12 0 14 2 4 6 16 18 20 200 175 150 125 100 75 50 8 22 Change in Debt 10 24 Unemployment 12 26 14 1920 1922 1924 1926 1928 1930 1932 1934 1936 1938 1940 1942 25 Change in Private Debt and Unemployment 0 1920 1930 1940 1950 1960 1970 1980 1990 2000 2010 2020 P ercent c hange in debt p.a . • Debt-focused analysis is why “Bezemer 12” did see the crisis coming: – http://mpra.ub.unimuenchen.de/15892/ – Bezemer 2010, 2011 14 0 12 2 10 4 8 6 6 8 4 10 2 12 0 0 14 2 16 4 18 6 20 22 10 Change in Debt Unemployment 12 Unemployment (U6) 26 8 14 1990 1992 1994 1996 1998 24 2000 2002 2004 2006 2008 2010 2012 P ercent u nem ploym ent (in verted) 225 Percent unemployment (inverted) 0 Percent change in debt p.a. 14 250 Percent of GDP Change in Private Debt and Unemployment 300 Dilemma for economics educators • What do you do when all you know is that you don’t know? • Continue teaching neoclassical economics – But from the originals, not the textbooks • Learn/teach your own school of thought properly • Teach the theory “warts and all” • Hire economists who know non-neoclassical economics – Teach parallel classes in the real Classical Economists – Attend those classes & learn some different questions – Engage with part of the discipline you have ignored for 40 years It ain’t Walras, Babe… • Neoclassical macro direct descendant of Bentham, Say, Walras, Marshall – Equilibrium, methodological individualism, strong reductionism, linearity • Unrelated to Classical Economists Smith, Ricardo, Marx, Keynes, Schumpeter, Fisher, Minsky, Goodwin – Dynamics, social classes, emergent phenomena, complexity & evolution • Non-neoclassical economics underdeveloped compared to neoclassical • Doesn’t have all the answers… – Many wrong ones—e.g., Labor Theory of Value in Marx – Some correct—e.g., Financial Instability Hypothesis It might be Marx, Schumpeter, Minsky… • But many correct questions – Focus on instability – Uncertainty – Crucial role of money – Disequilibrium dynamics • Better to ask the right questions than give accurate answers to the wrong ones – – – – Equilibrium fetish Risk as proxy for uncertainty Barter model of monetary economy Equilibrium Dynamics • an oxymoron in any real science • Given manifest failure of neoclassical macro, students must be exposed to non-neoclassical ideas Some resources • Debunking Economics II: almost all the economics you didn’t learn from the textbooks… • Available September 2011 • My blog www.debtdeflation.com/blogs – Minskian explanation of the crisis • Free software program “Minsky” – “Monetary Macro-dynamics for dummies” • Recently received INET grant – Mathematica version in development (Mike Honeychurch mike.honeychurch@gmail.com) – Prototype available on my blog: www.debtdeflation.com/blogs/QED • Lectures on history of economic thought, nonneoclassical monetary macroeconomics: http://www.debtdeflation.com/blogs/lectures References • • • • • • • • • • • • • Anderson, P. W. (1972). "More Is Different." Science 177(4047): 393-396. Bezemer, D. J. (2009). ““No One Saw This Coming”: Understanding Financial Crisis Through Accounting Models.” Groningen, The Netherlands, Faculty of Economics University of Groningen. Blatt, J. M. (1983). Dynamic economic systems : a post-Keynesian approach. Armonk, N.Y, M.E. Sharpe. Bezemer, D. J. (2009). “No One Saw This Coming”: Understanding Financial Crisis Through Accounting Models. Groningen, The Netherlands, Faculty of Economics University of Groningen. Bezemer, D. J. (2011). "The Credit Crisis and Recession as a Paradigm Test." Journal of Economic Issues 45: 1-18. Bezemer, D. J. (2010). "Understanding financial crisis through accounting models." Accounting, Organizations and Society 35(7): 676-688. Clark, J. B. (1898). "The Future of Economic Theory." The Quarterly Journal of Economics 13(1): 1-14. Friedman, M. (1969). The Optimum Quantity of Money. The Optimum Quantity of Money and Other Essays. Chicago, MacMillan: 1-50. Goodwin, R. (1967). A growth cycle. Socialism, Capitalism and Economic Growth. C. H. Feinstein. Cambridge, Cambridge University Press: 54-58. Keen, S. (1995). "Finance and Economic Breakdown: Modeling Minsky's 'Financial Instability Hypothesis.'." Journal of Post Keynesian Economics 17(4): 607-635. Keen, S. (2011). "A monetary Minsky model of the Great Moderation and the Great Recession." Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization In Press, Corrected Proof. Kirman, A. (1989). "The Intrinsic Limits of Modern Economic Theory: The Emperor Has No Clothes." Economic Journal 99 (395): 126-139. Lucas, R. E., Jr. (1972). Econometric Testing of the Natural Rate Hypothesis. The Econometrics of Price Determination Conference, October 30-31 1970. O. Eckstein. Washington, D.C., Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System and Social Science Research Council: 50-59. References • • • • • • • • • • • • • Lucas, R. E., Jr. (2004). "Keynote Address to the 2003 HOPE Conference: My Keynesian Education." History of Political Economy 36: 12-24. Kydland, F. E. and E. C. Prescott (1990). "Business Cycles: Real Facts and a Monetary Myth." Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis Quarterly Review 14(2): 3-18. Marx, K. and F. Engels (1885). Capital II. Moscow, Progress Publishers. Mas-Colell, A., M. D. Whinston, et al. (1995). Microeconomic theory. New York :, Oxford University Press. Minsky, H. P. (1982). Can "it" happen again? : essays on instability and finance. Armonk, N.Y., M.E. Sharpe. Solow, R. M. (2001). From Neoclassical Growth Theory to New Classical Macroeconomics. Advances in Macroeconomic Theory. J. H. Drèze. New York, Palgrave. Solow, R. M. (2003). Dumb and Dumber in Macroeconomics. Festschrift for Joe Stiglitz. Columbia University. Solow, R. (2008). "The State of Macroeconomics." The Journal of Economic Perspectives 22(1): 243-246. Samuelson, P. A. and W. D. Nordhaus (2010). Microeconomics. New York, McGraw- Hill Irwin. Schumpeter, J. A. (1934). The theory of economic development : an inquiry into profits, capital, credit, interest and the business cycle. Cambridge, Massachusetts, Harvard University Press. Shafer, W. and H. Sonnenschein (1993). “Market demand and excess demand functions”. Handbook of Mathematical Economics. K. J. Arrow and M. D. Intriligator, Elsevier. 2: 671-693. Sonnenschein, H. (1973). "Do Walras' Identity and Continuity Characterize the Class of Community Excess Demand Functions?" Journal of Economic Theory 6(4): 345-354. Varian, H. R. (1984, 1992). Microeconomic analysis. New York, W.W. Norton.