pathology-aspect-of-hypothalamus-and-pituitary

advertisement

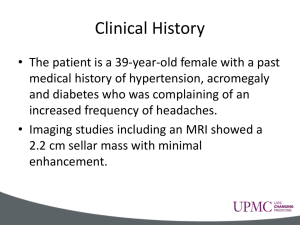

Pathology Aspect of Hypothalamus and Pituitary Gland By. Meike Rachmawati,dr Pathology anatomy Department Medical Faculty-Unisba Objective Pituitary neoplasm : Adenomas and hyperpituitarism : type of adenoma, morphology, and patophysiology Hypopituitarism Craniopharyngioma morphology : histogenesis and HYPERPITUITARISM AND PITUITARY ADENOMAS The most common cause of hyperpituitarism is an adenoma arising in the anterior lobe. Pituitary adenomas are classified on the basis of hormone(s) produced by the neoplastic cells, which are detected by immunohistochemical stains performed on tissue sections rarely, ultrastructural examination may be required to determine the specific lineage of the neoplastic cell. Pituitary adenomas can be functional (i.e., associated with hormone excess and clinical manifestations thereof) or silent (i.e., immunohistochemical and/or ultrastructural demonstration of hormone production at the tissue level only, without clinical manifestations of hormone excess). Both functional and silent pituitary adenomas are usually composed of a single cell type and produce a single predominant hormone, although exceptions are known to occur. Some pituitary adenomas can secrete two hormones (growth hormone and prolactin being the most common combination); rarely, pituitary adenomas are plurihormonal. Pituitary adenomas may also be hormone negative, based on absence of immunohistochemical reactivity and ultrastructural demonstration of lineage-specific differentiation. Clinically diagnosed pituitary adenomas are responsible for about 10% of intracranial neoplasms. They are discovered incidentally in as many as 25% of routine autopsies. In fact, the most recent data using high-resolution computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging suggest that approximately 20% of "normal" adult pituitary glands harbor an incidental lesion measuring 3 mm or more in diameter, usually a silent adenoma. Pituitary adenomas are usually found in adults, with a peak incidence from the 30s to the 50s. The adenohypophysis (anterior pituitary) releases six hormones that are, in turn, under the control of various stimulatory and inhibitory hypothalamic releasing factors: •ACTH, adrenocorticotropic hormone (corticotropin); •FSH, follicle-stimulating hormone; •GH, growth hormone (somatotropin); •LH, luteinizing hormone; •PRL, prolactin; and •TSH, thyroid-stimulating hormone (thyrotropin). The stimulatory releasing factors are : •CRH (corticotropinreleasing hormone), •GHRH (growth hormone-releasing hormone), •GnRH (gonadotropinreleasing hormone), •TRH (thyrotropinreleasing hormone). The inhibitory hypothalamic factors are: •growth hormone inhibitory hormone (GIH, or somatostatin) •PIF (prolactin inhibitory factor, or dopamine *For each of the pituitary cell types, the adenoma may be functional (producing symptoms of hormone excess) or silent. The heterogeneous category of "nonfunctional" adenomas includes silent pituitary adenomas and true hormone-negative adenomas (rare). ACTH, adrenocorticotropic hormone Classification of Pituitary Adenomas* Prolactin cell (lactotroph) adenoma Growth hormone cell (somatotroph) adenoma Thyroid-stimulating hormone cell (thyrotroph) adenomas ACTH cell (corticotroph) adenomas Gonadotroph cell adenomas Silent gonadotroph adenomas includes most socalled null cell adenomas Mixed (plurihormonal) adenomas Body Growth hormone-prolactin mixed adenomas most common Hormone-negative adenomas Most pituitary adenomas occur as isolated lesions. In about 3% of cases, however, adenomas are associated with multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1 (MEN-1, discussed later). Pituitary adenomas are designated, somewhat arbitrarily, microadenomas if less than 1 cm in diameter and macroademomas if they exceed 1 cm in diameter. Silent and hormone-negative adenomas are likely to come to clinical attention at a later stage than those associated with endocrine abnormalities and are therefore more likely to be macroadenomas; in addition, these adenomas may cause hypopituitarism as they encroach on and destroy adjacent anterior pituitary parenchyma. Morphology The usual pituitary adenoma is a well-circumscribed, soft lesion that may, in the case of smaller tumors, be confined by the sella turcica. Larger lesions typically extend superiorly through the sellar diaphragm into the suprasellar region, where they often compress the optic chiasm and adjacent structures As these adenomas expand, they frequently erode the sella turcica and anterior clinoid processes. They may also extend locally into the cavernous and sphenoidal sinuses. In as many as 30% of cases the adenomas are grossly nonencapsulated and infiltrate adjacent bone, dura, and (uncommonly) brain. Such lesions are designated invasive adenomas. Foci of hemorrhage and/or necrosis are common in larger adenomas. Microscopically, pituitary adenomas are composed of relatively uniform, polygonal cells arrayed in sheets, cords, or papillae. Supporting connective tissue, or reticulin, is sparse, accounting for the soft, gelatinous consistency of many lesions. The nuclei of the neoplastic cells may be uniform or pleomorphic. Mitotic activity is usually scanty. The cytoplasm of the constituent cells may be acidophilic, basophilic, or chromophobic, depending on the type and amount of secretory product within the cell, but it is fairly uniform throughout the neoplasm. This cellular monomorphism and the absence of a significant reticulin network distinguish pituitary adenomas from nonneoplastic anterior pituitary parenchyma (Fig. 20-4). The functional status of the adenoma cannot be reliably predicted from its histologic appearance. Gross view of a pituitary adenoma . This massive, nonfunctional adenoma has grown far beyond the confines of the sella turcica and has distorted the overlying brain. Nonfunctional adenomas tend to be larger at the time of diagnosis than those that secrete a hormone. Photomicrograph of pituitary adenoma. The monomorphism of these cells contrasts markedly to the mixture of cells seen in the normal anterior pituitary in Figure 20-1. Note also the absence of reticulin network. Clinical Manifestations of Pituitary Adenomas Prolactinomas: amenorrhea, galactorrhea, loss of libido, and infertility Growth hormone (somatotroph cell) adenomas: gigantism (children), acromegaly (adults), impaired glucose tolerance, and diabetes mellitus Corticotroph cell adenomas: Cushing syndrome, hyperpigmentation All pituitary adenomas, particularly nonfunctioning adenomas, may be associated with mass effects and hypopituitarism. SUMMARY The most common cause of hyperpituitarism is an anterior lobe pituitary adenoma. Pituitary adenomas can be macroadenomas (>1 cm) or microadenomas (<1 cm), and clinically, they can be functional or silent. Most adenomas consist of one cell type and produce one hormone, although there are exceptions. Mutation of the GNAS1 gene, which results in constitutive activation of a stimulatory G-protein, is one of the more common genetic alterations. The two distinctive morphologic features of most adenomas are their cellular monomorphism and absence of a reticulin network. HYPOPITUITARISM Hypofunction of the anterior pituitary may occur with loss or absence of 75% or more of the anterior pituitary parenchyma. This may be congenital (exceedingly rare) or may result from a wide range of acquired abnormalities that are intrinsic to the pituitary. Less frequently, disorders that interfere with the delivery of pituitary hormone-releasing factors from the hypothalamus, such as hypothalamic tumors, may also cause hypofunction of the anterior pituitary. Most cases of anterior pituitary hypofunction are caused by the following: Nonfunctioning pituitary adenomas (see above)Ischemic necrosis of the anterior pituitary is an important cause of pituitary insufficiency. In general, the anterior pituitary tolerates ischemic insults fairly well; loss of as much as half of the anterior pituitary parenchyma causes no clinical consequences. However, with destruction of larger amounts of the anterior pituitary (ε75%), signs and symptoms of hypopituitarism develop. Sheehan syndrome, or postpartum necrosis of the anterior pituitary, is the most common form of clinically significant ischemic necrosis of the anterior pituitary. During pregnancy the anterior pituitary enlarges considerably, largely because of an increase in the size and number of prolactin-secreting cells. However, this physiologic enlargement of the gland is not accompanied by an increase in blood supply from the lowpressure portal venous system. The enlarged gland is thus vulnerable to ischemic injury, especially in women who develop significant hemorrhage and hypotension during the peripartum The clinical manifestations of anterior pituitary hypofunction depend on the specific hormone(s) that are lacking. Children can develop growth failure (pituitary dwarfism) as a result of growth hormone deficiency. Gonadotropin or gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) deficiency leads to amenorrhea and infertility in women and decreased libido, impotence, and loss of pubic and axillary hair in men. TSH and ACTH deficiencies result in symptoms of hypothyroidism and hypoadrenalism, Prolactin deficiency results in failure of postpartum lactation. Craniopharyngioma Craniopharyngioma is a slow-growing, extra-axial, epithelial- squamous, calcified cystic tumor arising from remnants of the craniopharyngeal duct and/or Rathke cleft and occupying the (supra)sellar region. Two main hypotheses explain the origin of craniopharyngioma—embryogenetic and metaplastic Craniopharyngiomas are dysontogenic tumors with benign histology and malignant behavior, as they have a tendency to invade surrounding structures and recur after what was thought to be total resection. Craniopharyngioma usually presents as a single large cyst or multiple cysts filled with a turbid, proteinaceous material of brownish-yellow color that glitters and sparkles because of a high content of floating cholesterol crystals. Because of its appearance, it has been compared to machinery oil. It most frequently arises in the pituitary stalk and projects into the hypothalamus. Data from the Central Brain Tumor Registry of the United States (CBTRUS), collected between 1990 and 1993, revealed an average of 338 cases diagnosed annually with 96 occurring in children aged 0-14 years.13 Overall incidence was 0.13 per 100,000 per year. No variance by gender or race was found. Craniopharyngioma comprised 4.2% of all childhood tumors (ages 0-14 years). Distribution by age was bimodal, with peak incidence in children aged 5-14 years and older adults aged 65-74 years. International Incidence is 0.5-2 per 100,000 per year. Overall, craniopharyngioma accounts for 1-3% of intracranial tumors and 13% of suprasellar tumors. In children, craniopharyngioma represents 5-10% of all tumors and 56% of sellar and suprasellar tumors. No definite genetic relationship has been found and very few familial cases have been reported. Mortality/Morbidity In the United States, data collected during the periods 1985- 1988 and 1990-1992, coinciding with the introduction of CT scan, for the National Cancer Data Base (NCDB), indicate that survival rates were 86% at 2 years and 80% at 5 years after diagnosis. Survival rate varied by age group, with excellent rates for patients younger than 20 years (99% at 5 years). Survival rate was poor for those older than 65 years (38% at 5 years). Higher frequencies of all intracranial tumors have been reported from Africa, the Far East, and Japan; they are 18%, 16%, and 10.5%, respectively. Slight male predominance exists in all age groups (55%). Age of diagnosis varies widely; cases have been reported both in fetuses and in the elderly (age as high as 70 years). Age distribution is bimodal–the first peak is in children aged 5-10 years and a second one is in adults aged 50- Clinical manifestation Craniopharyngioma usually is a slow-growing tumor. Symptoms frequently develop insidiously and mostly become obvious only after the tumor attains a diameter of about 3 cm. Time interval between onset of symptoms and diagnosis ranges from 1-2 years. The most common presenting symptoms are headache (5586%), endocrine dysfunction (66-90%), and visual disturbances (37-68%). Three major clinical syndromes have been described and relate to the anatomic location of the craniopharyngioma. Prechiasmal localization typically results in associated findings of optic atrophy (eg, progressive decline of visual acuity and constriction of visual fields). Retrochiasmal location commonly is associated with hydrocephalus with signs of increased intracranial pressure (eg, papilledema, horizontal double vision). Intrasellar craniopharyngioma usually manifests with headache and endocrinopathy. Histopathologic Findings The histologic spectrum of craniopharyngioma includes 3 main types— adamantinomas, papillary, and mixed. Adamantinomatous craniopharyngiomas. Peripheral palisading of the epithelium is a pronounced feature (hematoxylineosin, x100). Frequently, the inner epithelium beneath the superficial palisade undergoes hydropic vacuolization and is referred to as the stellate reticulum (hematoxylineosin, x100). papillary craniopharyngiomas papillary craniopharyngio mas do not show complex heterogeneous architecture but rather are composed of simple squamous epithelium and fibrovascular islands of connective tissue (hematoxylineosin, x40). [ CLOSE WINDOW ] , x40). only simple squamous epithelium is seen in a papillary craniopharyngioma . The distinctive peripheral nuclear palisading, internal stellate reticulum, and nodules of "wet" keratin, which typify the adamantinomatous variant, are not seen in the papillary variant