Surgical considerations- summary of procedure including

advertisement

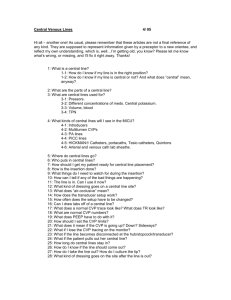

Esophagogastric Fundoplasty Natalya Hasan, MD Esophagogastric Fundoplasty • Performed with intent to prevent esophageal reflux in the following: – Persistent or recurrent symptoms despite maximizing medical therapy – Noncompliance – Severe esophagitis by endoscopy – Benign stricture – Barrett's columnar-lined epithelium (without severe dysplasia or carcinoma) – Recurrent pulmonary symptoms (eg, aspiration, pneumonia) in association with GERD – Laryngeal symptoms – Asthma Surgical Considerations Pre-operative evaluation of surgical candidates is not standardized. Generally, pts will have undergone at least one of the following: – Endoscopy - possibly one of the only preoperative tests if esophagitis is evident – Esophageal manometry - highly valuable as it can reveal disease states in which fundoplication would be contraindicated (e.g. achalasia or scleroderma). In addition, there is evidence, albeit inconclusive, that certain surgical approaches may be more efficacious if dysmotility is present Surgical Considerations: Pre-op Eval Cont’d – Esophageal pH monitoring - not highly specific as it generally will reveal increased acid exposure – Gastric emptying - of questionable value. It may reveal other etiologies of dyspepsia, but generally is done before surgery is even considered – Esophageal length — usually assessed by a set of plain films. If a markedly shortened esophagus or a large hiatal hernia that does not reduce in the upright position, surgeons may be inclined to perform a transthoracic approach Approaches • Transabdominal (open or laparoscopic) • Left Transthoracic Types of Fundoplasty Toupet Hill Belsey Mark IV Nissen http://www.nature.com/gimo/contents/pt1/images/gimo56-f8.jpg https://www.hon.ch/OESO/books/Vol_5_Eso_Junction/Articles/Images/2772f1.jpg Approaches • Most common - Nissen Fundoplication: anterior and posterior walls of stomach are sutured together around the lower esophagus with nonabsorbable sutures – Laparoscopic (LNF) • Initially met with skepticism • One RCT was prematurely terminated as it revealed that LNF was associated with a higher risk of developing dysphagia (and subsequent reoperation) than conventional Nissen (this criticism was later theorized to be attributable to surgeon’s experience). • More recent RCTs have shown that the LNF is not inferior, and may even be superior, to the open approach in that it is associated with fewer in-hospital complications and shorter hospitalization when performed by experienced surgeons. – Open - can be performed via transthoracic or transabdominal approach Anesthetic Considerations PRE-OP • Respiratory: Identify pts with hx of smoking, aspiration or asthma. Ordering a CXR prior to the case is not likely to change your management unless you think the pt has a current aspiration pneumonitis or asthma exacerbation. • Hematologic: Though EBL is usually <300, a pre-op CBC is often ordered. • GI: Obviously these patients have severe GERD. Pts should be encouraged to take their usual dose of PPI or H2 blocker on the AM of surgery. Pre-op (continued) • Cardiovascular: Patients presenting for an esophagogastric fundoplasty will be a variety of ages and possibly with multiple comorbidities. – The concept of “linked angina” describes the cardio-oesophageal reflex in pts with CAD. Studies have revealed that esophageal acid stimulation can reduce coronary blood flow in pts with CAD (i.e. non-cardiac chest pain can invoke cardiac chest pain). It is theorized that vagal tone plays a role, though neither the concept of linked angina nor the mechanism has been proven with certainty. – ASK about exercise tolerance Anesthetic Considerations INTRAOPERATIVE • • • • • • Induction: Modified RSI with cricoid (please refer to lecture slides dedicated to cricoid pressure for an evidence-based discussion). Pts with concomitant reactive airway disease may need beta-agonists following intubation. Maintenance: Standard inhalational or IV. Ongoing muscle relaxation or deepening of the anesthetic during certain times (e.g. trocar insertion or abdominal closure) will optimize surgical conditions. Nitrous should be avoided (increases volume of pneumoperitoneum, implicated in PONV). Emergence: Anticipate extubation. These patients are not ideal candidates for deep extubation given their hx of GERD and aspiration risk. As with induction, pts with reactive airway disease may have bronchospasm on emergence. Consider nebulizer treatment in PACU. Access: 1-2 IV Monitoring: Standard +/- arterial line if indicated by pt history +/- CVP in pts with difficult access Positioning: Laparoscopic - supine, Transthoracic - lateral decubitus. Clinical Scenario Pt is a 75 yo M, DM, HTN, COPD, former skin popper with esophagitis refractory to medical management who presents for a laparoscopic Nissen. After several attempts by you and your attending, the patient is getting quite upset and suggests that you just use a mask to put him to sleep. What do you do? Clinical Scenario You decide that he is not a good candidate for a mask induction given his GERD and decide to place a central line. You consent the patient, citing the risks of a central venous catheter as: 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. (try to fill in the blanks…answers will be revealed in later slide) Clinical Scenario You masterfully catheterize the right internal jugular vein using ultrasound guidance (and the needle-guide, of course, since you attended the central line placement workshop as a CA-1) in the OR. After placing standard monitors, you proceed with a rapid sequence induction with cricoid pressure. During direct laryngoscopy, you can’t see anything but the epiglottis. You’re surprised because the patient had been a Grade I view during a prior laryngoscopy. WHAT MIGHT BE THE PROBLEM? Clinical Scenario You suspect that the cricoid pressure of your very heavy-handed circulator might be the problem. After readjusting your assistant’s hand, the patients vocal cords come into view and you intubate the trachea. You secure the tube, hand off to the surgeons, and get started on charting. You check the schedule for tomorrow and see that you’re doing a hepatic resection. You call your anesthesia buddy who tells you to plan for an arterial line and central line because “that’s what we usually do.” So, you think to yourself, when should I place a central line? Central Lines: Common Indications * Hemodynamic monitoring - CVP via standard central venous catheters (vs. PCWP, CO, et al. via Swan-Ganz) * Administration of medications - e.g. infusions of pressors, TPN, chemotherapy * Transvenous cardiac pacing * Plasmapheresis, apheresis, hemodialysis, or continuous renal replacement therapy (requires special catheters that allow for high-flow - e.g. Quinton catheter, Trialysis catheter) * Poor peripheral venous access Central Lines: Complications •Infection (subclavian < internal jugular <<< femoral) •Arrhythmias •Vascular injury •Pneumothorax •Venous air embolism (on removal or with large boluses of air) •Bleeding Review: The Tracing Clinical Scenario You place a central line for the hepatic resection. The surgical attending says he needs you to keep the CVP low especially during the Pringle maneuver… 1) Why? 2) Is this a surgical myth or evidence-based? The role of central venous pressure and type of vascular control in blood loss during major liver resections Compares CVP ≤ 5 vs. ≥ 6 as well as method of vascular control (Pringle vs. Selective Hepatic Vascular Exclusion) in peri-operative bleeding and other outcomes (ICU stay, Hospital stay, Infection, et al.) Significant differences: – Blood loss with CVP ≥ 6 + Pringle = 1250 [250 to 2,850] – Blood loss with CVP ≤ 5 + Pringle = 780 [150 to 3,100] – Blood loss between the Pringle maneuver and SHVE was observed, only when CVP ≥ 6 – Hospital stay was also significantly longer in patients operated on with CVP ≥ 6 than in patients with CVP ≤ 5 – Authors’ Conclusions: Elevated CVP during major liver resections results in greater blood loss and a longer hospital stay. SHVEhas been shown not to be affected by CVP levels and should be used whenever CVP remains high despite adequate anesthetic management. Issues? • Authors make no mention of CVP trends. The only value considered was the CVP at time of commencement of liver resection. • The authors attribute the differences in post-op hospital stay to increased transfusion in the higher CVP group due to increased blood loss…but, those pts might have had higher CVPs due to comorbidities not present in the low CVP group (e.g. right heart failure) or elevated CVP as a result of ventilatory strategy (e.g. lung disease necessitating higher PEEP) Related article (same conclusion, similar shortcomings) • Wang WD, Liang LJ, Huang XQ, Yin XY. Low central venous pressure reduces blood loss in hepatectomy. World J Gastroenterol. 2006 Feb 14;12(6) What about CVP and fluid management? • Fact or fiction? Intraoperative CVP is a good indicator of fluid status. Intraoperative CVP is probably NOT a good indicator of fluid status. – Marik PE, Baram M, Vahid B. Does central venous pressure predict fluid responsiveness? Chest 2008 (134): 172-178. – Gelman S. Venous function and central venous pressure: A physiologic story. Anesthesiology 2008 (108): 735-748. – Magder S. Central venous pressure monitoring. Current opinion in critical care 2006. Board Review Methods to decrease the incidence of central venous catheter infections inculde all of the following EXCEPT: A. Using chlorhexidine over povidone-iodine for skin decontamination B. Unsing minocycline/rifampin impregnated catheters for suspected long term use C. Using the subclavian over the internal jugular route for access D. Using a single lumen over a multi-lumen catheter E. Changing the central catheter every 3 to 4 days over a guidewire. Board Review Methods to decrease the incidence of central venous catheter infections include all of the following EXCEPT: E. Changing the central catheter every 3 to 4 days over a guidewire. From Hall: Bloodstream infectious complications with central venous catheters are the most common late complication seen with central catheters (>5%). Current CDC guidelines do not recommend replacing central venous catheters. In addition, evidence is suggesting that the use of ultrasound may decrease the time needed to place catheters and the number of skin punctures needed for central vein access and may also decrease infections. Additional References • • • • • Bais JE, Bartelsman JF, Bonjer HJ; et al, The Netherlands Antireflux Surgery Study Group. Laparoscopic or conventional Nissen fundoplication for gastro-oesophageal reflux disease: randomised clinical trial. Lancet. 2000;355(9199):170-174 Broeders JA, Draaisma WA, Rijnhart-de Jong HG, Smout AJ, van Lanschot JJ, Broeders IA, Gooszen HG. Impact of surgeon experience on 5-year outcome of laparoscopic Nissen fundoplication. Arch Surg. 2011 Mar;146(3):340-6. Hall Brian and Robert Chantigian. Anesthesia: A comprehensive review. Philadelphia: Mosby, 2010. Jaffe Richard and Stanley Samuels. Anesthesiologist’s manual of surgical procedures. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams and Williams, 2004. Surgical management of gastroesophageal reflux in adults. In UpToDate, Friedberg JS and Talley NJ (Eds), UpToDate, Waltham, MA 2011.