Nutrition Support in the

Burn Patient

Recommendations from a review of

literature

Kaitlin Deason

And

Confidential Group Members

S

Case study

S A 31 year old white male trapped in a burning apartment building decided

to jump from a window. Preassessment by emergency personnel revealed

burns to his extremities, scalp, face, thorax, and back (an estimated 90%

total body surface area burn). It also appeared he sustained a tibula/fibula

fracture of the left leg and a crush injury of the right ankle. He was brought

into the emergency room on a 100% oxygen non-rebreathing mask. In the

emergency room he was promptly intubated with an oral 7.5 ETT because

of suspected inhalation burns. Appropriate analgesics and IV fluids were

administered and the patient was placed on mechanical ventilation. He was

immediately taken to the burn unit and tanked. He then went to surgery to

repair and stabilize his fractures. The following day his total body surface

area burns were reassessed from 90% to 60%.

Outline of literature review

S What to monitor

S Why and what type of nutrition support to

provide

S Macronutrient considerations

S Micronutrient considerations

Why are burn patients so

difficult to manage?

S Severe metabolic stress

S Extreme shifts in fluids

S Can be difficult to stabilize depending on

degree of injury

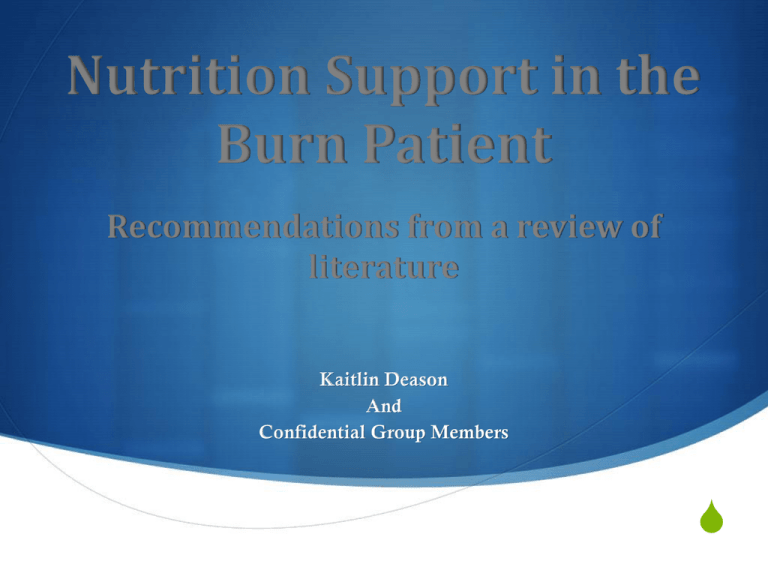

Initial monitoring

Indications for EN and TPN

S A burn patient has high nutrient and calorie needs, and

these needs are often not met by the patients’ oral intake

S Enteral and total parenteral nutrition are two methods to

feed a patient who is either not eating orally or who is not

eating enough.

S It is usually protocol of the burn unit that enteral nutrition

be started within 12 hours of admission via nasogastric or

nasojejunal tube so long as the gut is still functioning

Indications for EN and TPN

Con’t.

S Enteral nutrition is the preferred nutrition method

S An article by Chan & Chan (2009) states that “early

enteral feeding within 24 hours of hospitalization has

been shown to decrease the hypercatabolic response,

thus decreasing the release of catecholamine

glucagon, and weight loss, improve caloric intake,

stimulate insulin secretion, improve protein retention,

and shorten hospital length of stay.”

Indications for EN and TPN

Con’t.

S Nutrition support has been shown to decrease the risk

of infections in the burn patient

S One review showed intravenous infusions with trace

minerals zinc, copper and selenium administered

with a 0.9% saline solution started within twelve

hours after the injury and continued for fourteen

days after the burn had a 42% lower chance of

receiving an infection than the control group who

received normal saline

Macronutrient

recommendations

S The initial goal is to provide adequate nutrition,

prevent lean muscle losses, and provide adequate

fluids.

S Every burn patient needs to be treated as an

individual based on the degree of the burn and the

amount of stress caused to the body

Macronutrient

recommendations Con’t.

S The best estimate of energy needs would be to use

indirect calorimetry

S There is a difficult equation that can be used known

as the Ireton-Jones equation

S Takes into consideration trauma and burns

Macronutrient

recommendations Con’t.

S Caloric needs should be assessed to ensure the

patient is not losing weight more than 10% of their

usual body weight

S Medical nutrition therapy indicates that the caloric

needs can be increased by 20%-30% the normal

range to account for wound care and physical

therapy needs the patient will have

S Fluids needs can also double but the varies in each

case based on the degree of the burn.

Macronutrient

recommendations Con’t.

S Two important essential amino acids to burn

recovery are glutamine and arginine

S Glutamine serves as a primary oxidative fuel source for

rapid dividing cells because of this it has been shown to

be moderately beneficial in burn patients. Glutamine

also decreases protein muscle breakdown and increases

wound healing

S Arginine stimulates growth hormone, which is required

for wound healing . However more research needs to be

conducted about the safety

Micronutrient recommendations

S Micronutrients are essential in endogenous

antioxidant defense mechanisms and immunity

S Critically ill burn patients are at high risk of

selenium, zinc, copper, vitamin C and vitamin E

deficiency

S One study indicated that high-dose ascorbic acid

infusion reduced resuscitation fluid requirements

through an endothelial antioxidant mechanism

Micronutrient recommendations

con’t

S Copper, selenium and zinc are key nutrients for

wound healing and immune defense

S Copper is essential for wound repair

S Zinc is essential for wound healing

S Selenium is essential for the activity of glutathione

peroxidase (GSHPx)

S Part of the body’s first line of antioxidant defense in

both intra-and extracellular compartments

Micronutrient recommendations

S A prospective, randomized, placebo-controlled trial

conducted by Berger et al. (2007) showed that large

and early intravenous combining of copper,

selenium, and zinc supplementation reduced

infection and improved wound healing after major

burns

S Therefore, supplementation of these particular

trace elements may be beneficial, but more

research is needed

Conclusions

S Burn patients can be particularly challenging to

manage but the research shows that by providing

adequate protein and fluids along with the

recommended micronutrients and trace elements

the recovery of a burn patient can be greatly

enhanced through nutrition support.

S Clinicians should be particularly mindful of

macronutrients, micronutrients, monitoring, and

choosing the appropriate feeding method

References

Berger, M.M. (2006). Antioxidant micronutrient in major trauma and burns: evidence and practice. Nutrition in Clinical Practice,

21(5). Retrieved from http://ncp.sagepub.com/content/21/5/438.abstract doi: 10.1177/0115426506021005438

Berger, M.M., Baines, M., Raffoul, W., Benathan, M., Chiolero, R.L., Reeves, C., Revelly, J., Cayeux, M., Senechaud, I., &

Shenkin, A. (2007). Trace element supplementation after major burns modulates antioxidant status and clinical course by way

of increased tissue trace element concentrations. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 85(5), 1293-1300.

Chan, M.M., & Chan, G.M. (2009). Nutritional therapy for burns in children and adults. Nutrition (25)3, 261-269.

Curtis, C.S., & Kudsk, K.A. (2009). Enteral feeding in hospitalized patients: early versus delayed enteral nutrition. School of Medicine,

University of Virginia, USA. Retrieved from http://www.medicine.virginia.edu/clinical/departments/medicine/

divisions/digestive-health/nutrition-support-team/nutritionarticles/CurtisArticle. Pdf

Demling, R. H., DeSanti, L, & Orgill, D. P. (2004). Educating the burn care professionals around the world. Burnsurgery.org.

Retrieved from http://www.burnsurgery.org/

Gaby, A. (2010). Nutrition treatment for burns. Integrative Medicine (9)3, 46-51.

Hoffer, J. (2003) Protein and energy provision in critical illness. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 78, 906-911.

Mahan, L. K., & Escott-Stump, S. (2008). Krause's food, nutrition, & diet therapy. Philadelphia: W.B. Saunders.

Prelack, K., Dylewski, M., & Sheridan, R. L. (2007) Practical guidelines for nutritional management of burn injury and recovery.

Burns, 33, 14-24.