Paediatric long term ventilation: The right or wrong move?

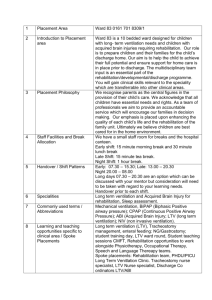

advertisement

A critical analysis based on case studies in Paediatric Intensive Care Unit, exploring the controversial issues surrounding the initiation of long term ventilation in children with chronic disease. Hannah Baird Supervisor: Dr P. M. Fortune Background LTV is defined as a medically stable child requiring mechanical ventilation for over three months Increase in the number of children receiving LTV in the UK, especially the number in the community No of children long term ventilated in the UK No ventilated at home 1993 (1) 24 9 1996 (1) 136 93 2000 (2) 241 - 2008 (2) 933* 844 *Despite being such a large increase only, 9.5% of this number are ventilated via a tracheostomy for 24h a day (2). Who needs LTV? Neuromuscular disorders are the most common conditions requiring LTV, closely followed by chronic respiratory conditions such as congenital hyperventilation syndrome. England (1) Congenital Hypoventilation syndrome Neuromuscular disease 18% 13% Spinal cord injury Craniofacial anomalies 4% 7% Non-cardiac congenital disease 12% 46% Broncho-pulmonary dysplasia Other Simple surgical interventions or infections can cause the lengthy PICU admissions. However.... Not all of the 933 children on LTV in the UK will require life–long ventilation, as their condition may improve. More research is needed into the outcomes of LTV and the transition into adult care for some CNS and neuromuscular patients. Aims To discuss, prompted by case studies the issues raised by initiating a child on LTV. This was done in terms of the resource, social and ethical implications. To understand when a situation can be defined as futile, and how this judgement can be made? To determine who the primary decision maker was; the doctor or the parent? Case study: Sophie* One and a half year old girl, been in PICU since birth Complex heart condition; including pulmonary atresia, VSD and a dilated right aortic arch Reduced life expectancy Ventilator dependent 24hr/day due to bronchomalacia She has suffered 2 cardiac arrests, episodes of bacteraemia, endocarditis and several thrombus formations Awaiting major cardiac surgery The surgery is very expensive, high risk of mortality and may still leave her dependant on a ventilator. Sophie is your patient, what would you do when she presented, would you have started LTV? Mind Map of the issues surrounding LTV. (3,4,) The Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health outlined five situations that can be regarded as futile: 5) The “Unbearable” situation – the child and/or their family feel that any further treatment when the illness is progressive and irreversible, is of little benefit(5). Summary LTV is expensive and raises many resource, social and ethical issues: Is it just to spend so much money of one child at the possible expense of another? UN convention of the rights of the child declares that every child has a ‘right to life and health’. When do we decide enough is enough? How do we define futility and who makes this call? What does best interest mean? How is this decision made? As the numbers and cost increase, these questions need to become increasingly more asked. Just because we can, doesn’t always mean we should. “Physicians are mandated to refuse to treat those who are over-mastered by their diseases, realising in such cases medicine is powerless.” Hippocrates (6) Unfortunately Sophie* passed away two days after the major cardiac surgery she had waited so long for. Questions? References 1. O’Toole. E.J, Wallis. J.Y.P. (1999). Current status of long term ventilation of children in the United Kingdom: a questionnaire survey. BMJ. 318.p295-318 2. Wallis.C, Payton.J.Y, Beaton.S, Jardine.E. (2010) Children on long term ventilatory support; 10 years of progress. Arch Dis Child. doi:10.1136/adc.2010.192864 3. Paediatric Intensive Care Audit Network. Information of the length of stay of long term ventilated patients 2005-2009. Information received via direct request. 4. Noyes. J, Lewis. M. (2005) From Hospital to Home. Barnardo’s publishers. Essex. pp 52, 69 5. RCPCH guidelines Withdrawing and Withholding Life Sustaining Treatment. The Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health. Withholding and Withdrawing Life Sustaining Treatment in Children: A Framework for Practice, 2nd edn. London: RCPCH, 2004. 6. Wellesley. H, Jenkins. I.A (2009). Withholding and Withdrawing life sustaining treatment in children. Paediatric Anaesthesia. 19. pp972978. General references: Kamm.M, Burger.R. Rimensberger.P. (2001). Survey of children supported by long term mechanical ventilation in Switzerland. Swiss medical weekly. 131. P261-266 Edwards. E. A, Hsiao. K, Nixon .G.M. (2005) Paediatric home ventilator support: The Auckland experience. Paediatric Child Health. 41. Pp652-658 Fraser. J (1997) Survey of occupancy of Paediatric Intensive care units by children who are dependent on ventilators. BMJ. 315 p347-348 Unicef: convention on the rights of the child. Available at www.unicef.org/crc/index_using.html . Accessed [10/06/2010] Beauchamp, T.L. Childress, James.F. (2009) .Principles of biomedical ethics. Sixth ed. Oxford University Press. New York. pp99-361 Bach .J.R, Vega. J, Majors. J ,Friedman A. (2003). Spinal Muscular Atrophy Type 1 Quality of Life. American Journal of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation. 82. pp137-142 Tibballs, J. (2007) Legal basis for ethical withholding and withdrawing lifesustaining medical treatment from infants and children. Journal of Paediatrics and Child Health. 43 p230-236 Nuffield council on Bioethics. Critical care decisions in fetal and neonatal medicine: ethical issues. Nuffield council on Bioethics. 2006 Garros.D, Rosychuk.R, Cox.P. (2003). Circumstances surrounding end of life issues in paediatric Intensive Care. American Journal of Paediatrics. 112. P371-379 Sharman.M.D, Kathleen.L. (2005). What influences parents’ decisions to limit or withdraw life support? Paediatric critical care medicine. 6 (5) p513-518