Monarch Watch - WordPress.com

advertisement

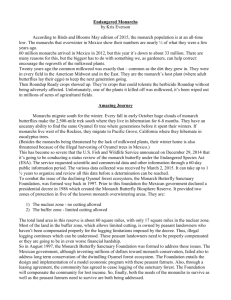

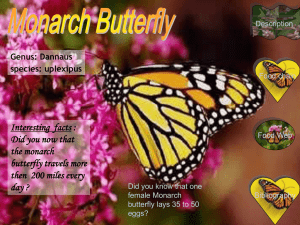

BBEMA’s Monarch Program Tracy Brown Executive Director Bedeque Bay Environmental Management Association (BBEMA) 1929 Nodd Road Emerald PE C0B 1M0 902-886-3211 www.bbema.ca Why Monarchs The monarch butterfly is known by scientists as Danaus plexippus, which in Greek literally means “sleepy transformation”. The name evokes the species ability to hibernate and metamorphize. Why Monarchs The Monarch Monarch Butterfly • Currently neither the United States nor Canada has designated protection status to any habitat along the major migration corridors for monarchs. Mexico has protected only tiny fragments of the habitat to which the monarchs migrate. • In 2008, the Commission for Environmental Cooperation (CEC), a tri-national organization covering the United States, Canada, and Mexico established by the North American Free Trade Agreement, published the North American Monarch Conservation Plan. The Plan identifies several factors that have contributed to the steady decline of monarchs across their native range. • On January 29 2014 a press conference in Mexico announced that the number of monarch butterflies hibernating in Mexico reached an all-time low in 2013 - Surveys of forested area used by hibernating monarchs in Mexico showed that just .67 hectares of forest were inhabited by monarchs during December 2013, a 44 percent drop from the same time the previous year. Endangered Phenomenon • Because so little protection is afforded these butterflies, the International Union for the Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources (IUNC) recognizes the annual migration of the monarch in North America as an endangered biological phenomenon. • The International Union for the Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources (IUCN) announced in 1983 that while the Monarch itself was not considered threatened; the migration to wintering sites in Mexico is an “endangered phenomenon,” the first time such a designation has ever been made. Endangered Phenomenon Threats to Monarchs in Breeding areas of the U.S. and Canada: • Many localities treat milkweed as a noxious weed and is destroyed (praying herbicide which destroys both the milkweed and adult nectaring plants) – mostly along highway edges, agricultural areas and in residential developments. • Pesticide use kills huge numbers of Monarch eggs, larva, and adults. • Habitat destruction for development of new roads, housing developments, commercial development, and agricultural expansion have negative consequences for Monarchs. • Degradation and loss of overwintering sites in California due to development; • Loss of breeding habitat across Canada and the United States due to the ongoing decline of native milkweeds (Asclepias spp.), their larval host plants • disease, parasitism, and predation. Endangered Phenomenon Threats to Monarchs in Mexico: • loss of overwintering sites in Mexico due to deforestation; • degradation of overwintering habitat in Mexico due to forest fires, diversion of water for human use, and poorly-regulated tourist activity; • In Mexico, the monarchs spend the winter in only about a dozen sites. Only some of these sites are protected from logging. Removing these valuable trees—for lumber, farming, and cattle grazing—destroys habitat and also creates gaps in the forest canopy, leaving roosting monarchs vulnerable Milkweed Delemma Monarchs must have milkweed. They have an obligate relationship with this family of plants. No milkweed = no monarchs. Milkweed is the only plant that monarch caterpillars eat. It is believed that both milkweed and monarchs evolved in the tropical regions of Mexico. As the milkweed adapted and its range extended, the monarch followed. All milkweed plants contain poisons known as cardiac glycosides. Monarch larvae are not affected by the poisons, but store them in the abdomen and wings of the adults - most birds that attempt to eat adults or larvae vomit and learn to associate this unpleasant experience with the bright patterns of the adults and larvae and thus soon learn to avoid them. Swamp Milkweed Swamp milkweed - Asclepias incarnata • Bloom time: last week of June through August and sometimes into September • Description - Swamp milkweed stands 0.9 to 1.5 metres high and is often found in large colonies. The flowers have elaborate hood and horn structures and are arranged in pink, flesh-coloured clusters. Leaves are opposite and lance shaped with short stalks. The seed pods, which mature between August and October, are slender and elongated and tapered at both ends. The juice of this plant is less milky compared to other milkweed species. • Habitat - This species is found in a range of wet conditions from standing water to saturated soil. It commonly occurs on stream banks, the shores of ponds and lakes, in sedge meadows, marshes and in low wet woods. • Swamp milkweed is a semi-aquatic plant that requires full sun exposure. This species is ideal for shoreline restoration. Seeds should be sowed in the late fall in outdoor flats and mulched lightly. Also known as: rose milkweed, silkweed, water nerve root, white Indian hemp, marsh milkweed Monarch Migration Monarchs don’t migrate south for food - they exist otherwise on stores of fat they accumulate along their journey south When they arrive in their wintering grounds, these butterflies enter a state called “diapause”, which means that they do not eat or reproduce. Instead, they join together in huge roosting groups, so numerous that tree branches have been known to break under their weight, and stir themselves only to seek water on sunny days. Adults that hatch in mid-summer in Canada will fly 3,000 kilometres reaching the Michoacan state of central Mexico by October •Monarch butterfly overwintering colonies are found in Mexico's oyamel fir forest, a unique mountain habitat. •Oyamel firs (Abies religiosa) grow only at high altitudes, between 2,400 and 3,600 meters. these forests is not as tropical as many might expect: daytime temps around 65 degrees and nights in the 30s Frequent Flyers • Traveling from southern Canada and across the U.S., monarchs fly on average up about 50 km a day, stopping to feed on nectar and to rest. • A monarch has been recorded to migrate at least 274 km in a single day. This fact is known because of a tagging recovery. The monarch was tagged at 1 p.m. in New Jersey. The very next day, it was recaptured at 5 p.m. in Virginia. • How Long? - People often wonder how long it takes one butterfly to migrate to Mexico. Tagging data can provide clues. The butterfly in this photo was tagged in South Dakota. It was found two months later in Texas, 1371 km away. This timing supports what we know about fall migration. Monarchs don't fly non-stop to Mexico. They feed, rest, and wait to travel until the wind is right. Frequent Flyers The further north the monarchs are the sooner they must begin their southward journey: • Monarchs in Eastern Canada will begin moving south as early as midAugust (peak migration period for Eastern Canada is in September) • Peak migration periods for the middle od the country is usually through September and October. Frequent Flyers • Migrating monarchs are larger and longer-lived than those that don’t migrate – and are built somewhat differently, with much larger bodies for storing fat and longer, larger wings for improved flight. • Often called the “super-generation” – this generation will live up to nine months, and only reproduce at the very end of their life when they begin their journey north again in the spring. Most monarch butterflies live about two to four weeks, eating and reproducing the whole time. • There are several theories about how monarchs that have never been to Mexico find the traditional roost the following fall. They may orient themselves based on the sun’s position or the earth’s magnetic field, by landscape features, or by a combination of these. Another theory claims that because of their small body size, monarch migration may be influenced by weather and climate conditions, such as wind Frequent Flyers • How High? - We can't see monarchs when they fly more than about 300 feet high. There is a gap overhead two miles high where monarchs can travel and we can't see them. BBEMA’s Monarch Watch Tagging Monarchs has a larger scientific purpose: Tagging programs are an attempt to learn more about this migratory phenomenon. To protect the species Scientists need data to answer questions • • How do the monarchs move across the continent, i.e. do they move in specific directions or take certain pathways? How is the migration influenced by the weather and are there differences in the migration from year to year? Only through the cooperative efforts of volunteer taggers will we be able to obtain sufficient recoveries and observations of the migration to answer these questions. Because monarchs have a certain "charisma" and a fascinating biology this project is a good way to introduce students to science and have them contribute to a scientific study. Through participation in this project we also hope to further interest in the conservation of habitats critical to the survival of the monarch butterfly and its magnificent migrations Viceroy butterflies look like monarchs to the untrained observer. How can you be sure which species you're seeing? Wings The coloring and pattern of monarch and viceroy wings look nearly identical. However, a viceroy has a black line crossing the postmedian hindwing. Size Viceroys are smaller than monarchs, although this size difference may be difficult to see in the field. Comparing wingspans: •Viceroy: 2 1/2 - 3 3/8 inches (6.3 - 8.6 cm). •Monarch: 3 3/8 - 4 7/8 inches (8.6 - 12.4 cm). Flight Viceroy flight is faster and more erratic. Monarch flight is float-like in comparison, with its characteristic "flap, flap, glide" pattern Tagging Monarchs Tagging Monarchs all-weather round polypropylene tags (9mm in diameter) – tags are numbered specifically for each tagging season. The Tagging Method We have adopted a tagging system in which the tag is placed over the large, mitten shaped cell (discal cell) on the underside of the hindwing of the monarch. Male Monarch: Notice the thin vein pigmentation and swollen pouches on the hindwings. Female Monarch: Notice the thick vein pigmentation and no hindwing pouches. Tagging Monarchs Monarch Waystation Monarch Waystations Adult butterflies crave nectar from flowers -- the more, the better. Some flowers contain more nectar, and it is these that will be most effective in attracting butterflies. Flower color can also be important, with more vibrant colors attracting butterflies more readily -- especially when single colors are grouped in masses. Butterflies are near-sighted and are more easily attracted to large stands of a particular color. the successful butterfly garden consists of the following components: • Host plants for caterpillars. • Nectar plants for adults. • Abundant sunshine. • Wet sand or mud puddles in shady nooks. • Shelter from high winds. • An environment kept healthy through the absence of insecticides. Butterfly Gardens Wildflowers as Caterpillar Food • Monarch butterfly caterpillars - Common milkweed (Asclepias syriaca)- technically considered non native and potentially invasive on PEI - use Swamp Milkweed • Red clover (Trifolium pratense): Clouded sulfur butterfly caterpillars. Perennial Flowers as Caterpillar Food • Hollyhocks (Alcea rosea): Painted Lady and checkered skipper butterfly caterpillars. • Steeple bush, or meadow sweet (Spiraea tomentosa): Spring azure blues. Annual Flowers as Caterpillar Food • Cosmos (Cosmos bipinnatus): Painted Lady. • Zinnia (Zinnia elegans): Silver-spotted skipper butterfly caterpillars Adult Butterfly Food • Butterfly bushes (Buddleja davidii) - Monarchs • Purple coneflower (Echinacea purpurea) • Goldenrod (Solidago canadensis) • Joe Pye weed (Eupatorium maculatum) • Violets (such as Viola papilionacea) BBEMA’s Monarch Program Questions???