For the governance pillar, agencies will

advertisement

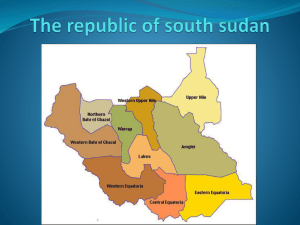

Making the Transition from Relief to Development Presentation to UNDP, UNFPA and UNOPS Executive Board 9 September 2011 Lise Grande, DSRSG/RC/HC/UNDP Resident Representative . The new Republic of South Sudan is undergoing a complex transition South Sudan has made impressive achievements since the Comprehensive Peace Agreement was signed six years ago. Basic state structures have been created from scratch: • 29 ministries and 17 independent commissions and chambers have been established • An elected Legislative Assembly is fully functioning • State Governor’s offices and State Assemblies have been established • Key rule of law institutions, including a police service, a prison service, and a judiciary, have been established Basic services and infrastructure are also improving: • Over 6,000 kilometers of dirt road have been upgraded, linking major cities and towns • Primary school enrollment has quadrupled and the number of school buildings has increased by 20 percent • The first midwifery school has been established in Juba where midwives are being trained to fill a critical gap in frontline maternal health care Yet, the critical tasks for the new state remain overwhelming in scale and complexity South Sudan has the largest capacity gap in Africa. Every single ministry, state government and spending agency lacks qualified, competent staff. Nearly half of all civil servants have only a primary education and fewer than 5 per cent have higher degrees. It will take a generation to improve the capacity of the public service. South Sudan has some of the worst human development indicators in the world. More than 80 per cent of the population lives on less than USD 1 per day. Only 20 per cent use a health facility during their lifetime. The maternal mortality rate is the worst in the world. Less than 6 percent of children are fully immunized and half do not attend school. 92 per cent of women are illiterate. A 15 year old girl has a higher chance of dying in childbirth than finishing school. South Sudan is one of the world’s most underdeveloped countries. In a country the size of France, there are only a handful of allweather roads. Up to 60 per cent of remote locations are inaccessible during the rainy season. There is no electricity grid, no national energy system and no civil aviation capacity. Farmers can not access markets so there is no incentive to produce. Many areas are insecure because they are inaccessible, and state structures have little if any capacity to access to intervene when conflict occurs. South Sudan presents the single largest state-building challenge of our generation Insecurity remains the single greatest threat • The Government is currently fighting five armed militias in strategically vital areas of South Sudan and tensions are rising along the border • SPLA commanders estimate that only 30 per cent of soldiers are under their full command and control • Leaders have been unable to address ethno-political rifts, unresolved grievances, and a lack of opportunities for youth, all of which continue to drive local conflicts The largest semi-peacetime movement of people since World War II is taking place in South Sudan • Since 30 October 2011, 340,000 South Sudanese have returned from the north and in 2011, over 300,000 persons have been newly displaced due to conflict • Returnees and ex-combatants from the SPLA and other armed groups need to be reintegrated into communities where basic infrastructure, basic services, and livelihood opportunities are lacking Strategic Priorities During the Transition At Independence there is still fundamental instability State-building is the priority that trumps all others The situation in South Sudan challenges our common conceptions about transition. Most transitions are about getting state systems to start functioning again. In South Sudan, however, state systems haven’t been established because of the long war and decades of marginalization. The concept of ‘recovery’ doesn’t make sense since there are no structures or systems to ‘recover’. The transition from relief to development is taking place at the same time that the state itself is being built from scratch. Because expectations are so high and so much is at stake, the government doesn’t have generations to build the state. The new Republic is it racing time against time to establish viable institutions capable of maintaining peace and security, accountably managing public resources and delivering public goods and services to one of the poorest populations in the world. At Independence there is still fundamental instability Responding to the challenges facing South Sudan requires a new way of working Throughout the Interim Period of the Comprehensive Peace Agreement, the bulk of international assistance has been directed towards humanitarian programmes, which have contributed little to towards building state structures and resulted in the state not being held accountable for the delivery of public services. This needs to change. The UN needs to shift gears and help the Government to prioritize and focus on: • • • • establish core state functions stabilizing insecure areas build delivery systems for basic public goods and services introduce redistributive programmes that give people the confidence that the state is there for them Because the transition is so complex and difficult, agencies need to focus on only a handful of simple, transformative programmes that can be done at scale. Agencies need to manage extreme levels of fiduciary risk, move very quickly while also being prepared to change course and adopt new strategies and reduce transaction costs by minimizing complex bureaucratic procedures and programming processes. Because everything depends on the state, agencies will focus on core functions and the capacity gap Agencies will work with partners to put in place core governance functions. Over the past two years, the UN and partners have been helping the Government to prioritize and focus on building the core state functions essential for service delivery and economic growth. These include systems for: • • • Management of public resources Maintenance of basic law and order Management of the public service Agencies will also help to bridge the capacity gap by rapidly augmenting existing capacities and providing onthe-job mentoring support. This includes: • placing United Nations volunteers in every state to support core functions • embedding civil servants from Ethiopia, Uganda and Kenya into Ministries and twinning with South Sudanese counterparts • Launching a partnership with the African Union through which 1,000 technical specialists will support public services across South Sudan The UNV ‘surge’ initiative is one of the most popular programmes in South Sudan Ephrem Israel, from Ethiopia, is a Development Planning Specialist helping the State Ministry of Finance to plan and budget for the needs of the people of Northern Bahr el Ghazal State ‘Surge’ initiatives have successfully been used in Botswana, East Timor and Afghanistan and need to be expanded here. Shekhar Shrestha, from Nepal, is a Civil Engineer working closely with the State Ministry of Infrastructure overseeing major construction works on roads and buildings Simeo Nsubuga, from Uganda, is a Law Enforcement Advisor who assists the State Police Headquarters in strengthening the rule of law in Western Bahr el Ghazal State Nicholas Jonga, from Zimbabwe, is a Statistician working to assist the Government with evidencebased planning and budgeting for the people of Jonglei State Because stability is so important, UNMISS and agencies will focus on extending state authority into insecure areas Insecurity remains a chief impediment to the expansion of services and growth. Insecure areas lack government presence, law enforcement or any effective application of the rule of law. They have the largest concentration of vulnerable and displaced persons and therefore the largest humanitarian and emergency programmers and presence. Extending state authority into insecure areas and doing so in way in which the legitimacy and credibility of state authority increases is crucial to stabilization and any prospect for a successful transition from relief to development. This is a chief area for collaboration between UNMISS and the country team. This means providing direct support to and through the state and local governments so that government structures can actually take control, rather than state authority being undermined as can happen when external parties and contractors provide the assistance. The UN will be helping the Government do this by: • providing support to allow local government to lead interactions with their constituents and stakeholders, including youth, women, the church and civil society groups. • helping to expand access to justice and protection, particularly in areas where the state’s armed forces are seen as being part of the problem. Because people need confidence in their state, agencies will focus on helping to establish service delivery systems and establishing a social compact between the Government and its people Following independence, expectations are high. The Government has a small window of opportunity to establish itself as viable, legitimate and responsive to people’s needs. Although security remains an overriding priority, the Government needs to spend more than 14 per cent of the national budget on health, education and social services. Bold initiatives aimed at consolidating the social compact include the introduction of child benefit and the launching of a “national solidarity” programme that will reach each county To fight the perception that only elites are benefitting from independence, the Government needs to adopt policies that redistribute national wealth so that it reaches the poorest households and reduces the “deadly decisions” that South Sudanese families confront daily. This is best done by bringing service delivery to scale through simple transformative programmes. The UN will help the Government do this by: • tackling the maternal mortality through cascading training that builds up a new cadre of village midwives • Supportingteacher training as part of a mass campaign to boost access to education • tackling the exceptionally high levels of illiteracy through a major national literacy campaign Each day in South Sudan, families try to decide how to spend their one dollar Will the family use their dollar to: Buy a second meal? Buy wood for the family stove? Buy thatching for the roof? Buy anti-malarials for their ill child? Buy school uniforms and materials? Pay bribes at the market checkpoint? Buy agricultural inputs? The approach of the UN agencies to social progress and justice is based on reducing the seven “deadly decisions” that the average family makes every day Although needs are overwhelming, prioritization is key The UN agencies will align their programmes with the South Sudan Development Plan’s four pillars: Social and Human Development, Economic Development, Governance, and Conflict Prevention and Security For the social and human development pillar, agencies will: • Build South Sudanese capacity to deliver services • Promote child rights and combat gender-based violence For the economic development pillar, agencies will: • Accelerate inclusive growth and diversify the economy • Improve agricultural production and access to markets • Create an enabling environment for private sector • Address youth unemployment through labour-intensive works For the governance pillar, agencies will: • Improve the Government’s capacity to deliver core state functions and public services • Strengthen accountability and oversight mechanisms • Strengthen rule of law and access to justice • Improve protection for women and children For the conflict prevention and security pillar, agencies will: • Help to reintegrate returning populations • Support accelerated demobilization, disarmament and reintegration • Support stability and community security A joined up prioritized approach within the UN will be crucial to consolidate peace during the first years of statehood In summary, lessons learned from other transitions show that it is important for the UN to: 1) Not try to do too much and be prepared to take tough decisions about priorities 2) Not to overwhelm national structures and overburden national authorities 3) Ensure that humanitarian programmes are coordinated with government delivery by incorporating humanitarian clusters into sector-wide structures as soon as possible 4) Reach out to other partners to create a common sense of purpose and to avoid gaps in key areas UN planning in South Sudan is being joined up to ensure a system-wide realistic, prioritized approach to the most important tasks. The Consolidated Appeal will present a summary of emergency needs and the emergency programmes which UN agencies and hundreds of national and international NGOs intend to implement. This year’s appeal will include sections describing the phased incorporation of the cluster system into the Government’s sector-wide coordination mechanisms and the “shut-down” of humanitarian funding windows as basket funds for service sectors are established. The United Nations Development Assistance Framework involving the 23 agencies, funds and programmes in South Sudan, is currently being prepared. This plan will include a highly prioritized set of programmes identified by the government as crucial for the successful implementation of the South Sudan Development Plan. A joint UN peace building plan will be developed for UNMISS and UN Country Team, and other bilateral and multilateral partners as entailed in SCR 1996 Para 18. This plan will prioritize specific peace building tasks related to key issues of state-building and development. It will help to establish the conditions for development and will be aligned with national priorities.