CHAPTER 18

Late Adulthood: Social and Emotional

Development

Theories of Social and Emotional

Development in Late Adulthood

Theories of Social and Emotional Development

in Late Adulthood

• Erikson’s psychosocial theory

– Eighth or final stage of life is called ego integrity or despair; he believed

people who achieved positive outcomes to an earlier life crisis would be

more likely to obtain ego integrity than despair in late adulthood

• Ego integrity versus despair

– Basic challenge is to maintain the belief that life is meaningful and

worthwhile in the face of physical decline and the inevitability of death;

ego integrity derives from wisdom, as well as from the acceptance of

one’s lifespan as being limited and occurring at a certain point in

history; adjustment in the later years requires wisdom to let go

Robert Peck’s Developmental Tasks

• Peck outlined three developmental tasks that people

face in late adulthood

– Ego differentiation versus work-role preoccupation

– Body transcendence versus body preoccupation

– Ego transcendence versus ego preoccupation

• Ardelt (2008) writes that ego transcendence grows out

of self-reflection and willingness to learn from

experience.

– Ego transcendence is characterized by a concern for the wellbeing of humankind in general, not only of ourselves and those

we love.

Robert Butler’s Life Review

• Butler (2002) suggests reminiscence is a normal aspect

of aging.

– People can be extremely complex and nuanced.

– They can be incoherent and self-contradictory

– Life reviews attempt to make life meaningful, to help people

move on with new relationships as others in their lives pass on,

and to help them find ego integrity and accept the end of life.

• Butler (2002) argues helping professionals rely too

much on drugs to ease the discomforts of older adults.

– Pilot programs suggest therapists may be able to relieve

depression and other psychological problems in older adults by

helping them reminisce about their lives.

Disengagement Theory

• Disengagement theory

– Older people and society mutually withdraw from one another

as older people approach death.

– People in late adulthood focus more on their inner lives,

preparing for the inevitable.

– Government or industry now supports them through pensions or

charity rather than vice versa.

– Family members expect less from them.

– Older people and society prepare to let go of one another.

• Well-being among older adults is predicted by pursuing

goals, rather than withdrawal.

Activity Theory

• Activity theory

– Older adults are better adjusted when they are more active and

involved in physical and social activities.

• Physical activity is associated with a lower mortality rate

in late adulthood.

– Leisure and informal social activities contribute to life

satisfaction among retired people.

– Israeli study found benefits for life satisfaction in activities

involving the next generation, the visual and performing arts,

and spiritual and religious matters, but there was also value in

independent activities in the home

Socioemotional Selectivity Theory

• Socioemotional selectivity theory

– Looks at older adults’ social networks

– Theory of motivation hypothesizes increasing emphasis is

placed on emotional experience as we age

– Research by Carstensen et al. (1999) indicated proportion of

emotional material recalled increased with the age group,

showing greater emotional response of older subjects.

• Social contacts limited to a few individuals who are of

major importance to us as we grow older

• Does not mean older adults are antisocial

– See themselves as having less time to waste and they are more

risk-averse

– They do not want to involve themselves in painful social

interactions

Psychological Development

Self-Esteem

• Robins et al. (2002)

– Recruited more than 300,000 individuals, who completed an

extensive online questionnaire that provided demographic

information and measures of self-esteem

– Results indicated self-esteem of males was higher than that of

females

– Self-esteem highest in childhood and dips with entry into

adolescence

– Self-esteem then rises gradually throughout middle adulthood

and declines in late adulthood, with most of the decline

occurring between the 70s and the 80s

– All this is “relative”

– The measure of self-esteem is above the mid-point of the

questionnaire for adults in their 80s

Fig. 18-2, p. 375

Self-Esteem (cont’d)

• Drop in self-esteem may be due to life changes such as

retirement, loss of a spouse or partner, lessened social

support, declining health, and downward movement in

socioeconomic status

– Or older people are wiser and more content

• Older people express less “body esteem”

– Older men express less body esteem than older women

– Men more likely to accumulate fat around the middle, women

accumulate fat in the hips

– Sexual arousal problems more distressing for the male

– Older adults with poor body esteem tend to withdraw from

sexual activity, often frustrating their partners.

Independence/Dependence

• Older people who are independent think of themselves

as leading a “normal life”.

– Those who are dependent on others, even only slightly

dependent, tend to worry more about aging and encountering

physical disabilities and stress.

• A study of 441 healthy people aged 65-95 found

dependence on others to carry out the activities of daily

living increased with age (Perrig-Chiello et al., 2006).

• Interviews of stroke victims found independence in

toileting is important in enabling older people to avoid

slippage in self-esteem (Clark & Rugg, 2005).

Depression

• Affects some 10% of people aged 65 and above

• Depression in older people sometimes a continuation of

depression from earlier periods of life and sometimes a

new development

• Appears to have multiple origins

– Can be connected with the personality factor of neuroticism

– Possible structural changes in the brain

– Possible genetic predisposition to imbalances of the

neurotransmitter noradrenaline; may be link between

depression and physical illnesses such as Alzheimer’s disease,

heart disease, stroke, Parkinson’s disease, cancer

Depression (cont’d)

• Depression is connected with the loss of friends and

loved ones, but depression is a mental disorder that

goes beyond sadness or bereavement.

• Loss of companions and friends will cause profound

sadness, but mentally healthy people bounce back

within a year or so.

• Depression goes undetected, untreated in older people

much of the time.

– May be overlooked because symptoms are masked by physical

complaints such as low energy, loss of appetite, and insomnia

– Healthcare providers tend to focus on older people’s physical

health than their mental health

Depression (cont’d)

• Depression connected with memory lapses and other

cognitive impairment, such as difficulty concentrating

• Some cases of depression are simply attributed to the

effects of aging or misdiagnosed as dementia, even

Alzheimer’s disease

• Depression in older people can usually be treated

successfully with the same means that work in younger

people, such as antidepressant drugs and cognitivebehavioral psychotherapy.

Depression (cont’d)

• Untreated depression can lead to suicide, which is most

common among older people.

• Highest rates of suicide found among older men who

– have lost their wives or their partners

– lost their social networks

– fear the consequences of physical illnesses and loss of freedom

of action

• Fewer older adults suffer from depression than younger

adults, suicide is more frequent among older adults,

especially Caucasian men.

Anxiety Disorders

• Anxiety disorders affect at least 3% of those aged 65

and above, but coexist with depression in about 8% to

9% of older adults.

• Most frequently occurring anxiety disorders among older

adults are generalized anxiety disorder (GAD) and

phobic disorders.

– Panic disorder is rare

– Agoraphobia affecting older adults tends to be of recent origin

and may involve the loss of social support systems due to the

death of a spouse or close friends.

– GAD may arise from the perception that one lacks control over

one’s life.

Anxiety Disorders (cont’d)

• Anxiety disorders increase levels of cortisol (a stress

hormone).

– Takes time for them to subside

– Cortisol suppresses functioning of the immune system, so that

people are more vulnerable to illness.

• Mild tranquilizers are commonly used to quell anxiety in

older adults.

• Psychological interventions

– Cognitive-behavior therapy

• Shows therapeutic benefits in treating anxiety in older adults

• Does not carry the risk of side effects or potential dependence

Social Contexts of Aging

Communities and Housing for Older People

• Older Americans report that they prefer to remain in

their homes as long as their physical and mental

conditions allow them.

• Older people with greater financial resources, larger

amounts of equity in their homes, and stronger ties to

their communities are more likely to remain in their

homes.

• Older people with declining health conditions, changes

in their family composition, and significant increases in

property taxes and costs of utilities are likely to need to

consider residing elsewhere.

Communities and Housing for Older People

(cont’d)

• Older people who live in cities, especially inner cities,

are highly concerned about exposure to crime,

particularly crimes of violence.

– Most concerned

• People of advanced old age (80 and above), in poor health, and of

depressed mood

• People aged 80 and above less likely to be victimized

than people in other age groups

– Social support helps older people cope with their concerns

about victimization

– If victimized, it helps them avoid some of the problems that

characterize posttraumatic stress disorder

Communities and Housing for Older People

(cont’d)

• Older people who can no longer manage living on their

own may have access to home health aides and visiting

nurses to help them remain in the home.

• Affluent older people may be able to afford to hire

round-the-clock or part-time live-in help.

– Others may move in with adult children

– Others may move into assisted living residences in which they

have their own apartments but community dining rooms and

nursing aid with physicians on call and available in the facility

Communities and Housing for Older People

(cont’d)

• Older adults who relocate to residences for the elderly,

whether or not they have facilities for assisted living,

tend to experience disrupted social networks and

challenges for finding new friends and creating new

networks.

• Residences should have communal dining facilities and

organized activities, including transportation to nearby

shopping and entertainment.

– Residents take time in engaging other people socially and are

selective in forming new relationships.

Communities and Housing for Older People

(cont’d)

• Older adults may be most reluctant to relocate to nursing

homes because nursing homes signify the loss of

independence.

• Surveys indicate that older adults are relatively more

willing to enter nursing homes when they perceive

themselves to be in poor health and when one or more

close family members live near the nursing home.

• “Elder abuse”

– Staff acts harshly toward residents, sometimes in response to

cognitively impaired residents acting aggressively toward the

staff; well-selected and well-trained staff can deal well with

impaired residents

Religion

• Religion involves participating in the social, educational,

and charitable activities of a congregation as well as

worshiping.

– Religion and religious activities provide a vast arena for social

networking for older adults.

• As people undergo physical decline, religion asks them

to focus, instead, on moral conduct and spiritual, not

physical, “substance” such as the soul

– Studies find religious involvement in late adulthood is usually

associated with less depression and more life satisfaction as

long as it is done in moderation.

Religion (cont’d)

• Frequent churchgoing associated with fewer problems in

the activities of daily living among older people

• Older African Americans who attend services more than

once a week live 13.7 years longer, on average, than

their counterparts who never attend church

• In-depth interviews with the churchgoers find reasons

such as the following for their relative longevity

– avoidance of negative coping methods such as aggressive

behavior and drinking alcohol

– evading being victimized by violence

– hopefulness

– social support

Marriage

• 20% to 25% of marriages last half a century or more,

only to end with the death of one of the spouses.

• Couples report less disagreement over finances,

household chores, and parenting/grandparenting.

• Concerns about emotional expression and

companionship

– Older couples show more affectionate behavior when they

discuss conflicts, and they disagree with one another less in

general.

– Similarity in personality is less of a contributor to conflict than in

midlife, consistent with the finding that similarity in

conscientiousness and extraversion is no longer strongly

associated with marital dissatisfaction.

Divorce, Cohabitation, and Remarriage

• Older adults less likely than younger adults to seek

divorce; fear of loss of assets, family disruption, and

relocation, and older adults do not undertake divorce

lightly

– If divorcing, often because they belong to an aberrant marriage

that is punitive or because one of the partners has taken up a

relationship with an outsider

• 4% of older adults of the unmarried population cohabit

– Less likely than younger people to wish to remarry

– Older cohabiters report being in more intimate, stable

relationships.

– Younger cohabiters see their lifestyle as a prelude to marriage,

older cohabiters are more likely to see their relationship as an

alternate lifestyle.

Gay and Lesbian Relationships

• Gay men and lesbians in long-term partnerships tend to

enjoy higher self-esteem, less depression and fewer

suicidal urges, and less alcohol and drug abuse.

• Gay men in long-term partnerships are also less likely to

incur sexually transmitted infections.

• Gay men and lesbians sometimes form long-term

intimate relationships with straight people of the other

sex; relationships do not involve sexual activity, but the

couples consider themselves to be “family” and are

confidants.

Widowhood

• Middle-aged male widowers are relatively more capable

of dealing with their loss than older males.

• Men and women need to engage in the activities of daily

living (taking care of their personal hygiene, assuming

the responsibilities that had been handled by their

spouse, and remaining connected to the larger social

community).

• Widowhood more likely to lead to social isolation than is

marital separation

– Reasons for isolation are physical, cognitive, and emotional

Widowhood (cont’d)

• Widowhood leads to a decline in physical and mental

health, including increased mortality and deterioration in

memory functioning.

• Loss of a spouse heightens risks of depression and

suicide among older adults, more so among men than

women.

• Men who are widowed are more likely than women to

remarry, or at least to form new relationships with the

other sex.

– Women, more so than men, make use of the web of kinship

relations and close friendships available to them.

– Men may be less adept than women at various aspects of self

and household care.

Singles and Older People without Children

• Single older adults without children just as likely as

people who have had children to be socially active and

involved in volunteer work

– Tend to maintain close relationships with siblings and long-time

friends

– Very old (mean age = 93) mothers and women who have not

had children report equally positive levels of well-being

• Married older men without children appear to be

especially dependent on their spouses.

• Parents seem to be more likely than people without

children to have the social network that permits them to

avoid nursing homes or other residential care upon

physical decline.

Siblings

• Older sibling pairs tend to give each other emotional

support.

– True among sisters (women more likely than men to talk about

feelings) who are close in age and geographically close

• After being widowed, siblings (and children) tend to

ramp up their social contacts and emotional support.

– Support begins to decrease within two to three years

– A sibling, especially a sister, often takes the place of a spouse

as a confidant

• Twin relationships more intense in terms of frequency of

contacts, intimacy, conflict, and emotional support

– Frequency of contact and emotional closeness declines from

early to middle adulthood, but increases again in late adulthood

(mean age at time of study = 71.5 years)

Friendship

• Older people narrow friendships to friends who are most

like them and share similar activities.

• To regulate their emotions, they tend to avoid “friends”

with whom they have had conflict over the years.

• Friends form social networks that keep elders active and

involved.

• Friends remain confidants with whom older adults can

share feelings and ideas.

Friendship (cont’d)

• Friends provide emotional closeness and support.

• Friendships help older adults avert feelings of

depression.

• Social networking helps with physical and psychological

well-being of older adults in the community and in

residential living facilities.

• Older adults have a difficult time forming new

friendships when they relocate; with time, patience, and

encouragement, new friendships can develop.

Adult Children and Grandchildren

• Grandparents provide a perspective on the behavior

and achievements of their grandchildren they might not

have had with their own children.

• Both cohorts view each other in a positive light and see

their ties as deep and meaningful.

• Grandparents-grandchildren conceptualize their

relationships as distinct family connections that involve

unconditional love, emotional support, obligation, and

respect.

• Grandparents and adult grandchildren often act as

friends and confidants.

– Their relationship can seem precious, capable of being cut short

at any time

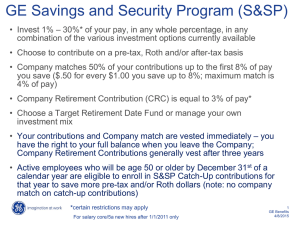

Retirement

Retirement and Retirement Planning

• The average person has two decades of life in front of

him or her at the age of 65, indicating a need for

retirement planning (Arias, 2011).

• Retirement planning may include regularly putting

money aside in plans (IRAs, Keoghs, and various

pension plans in the workplace).

– Investing in stocks, bonds, or a second home

• Older people may investigate the kinds of healthcare

and cultural activities that are available in other

geographic areas of interest.

– If they are thinking of another area, they will also be interested

in learning about the weather and crime statistics

Retirement and Retirement Planning (cont’d)

• Couples in relationships—including married

heterosexuals, cohabiting heterosexuals, and gay and

lesbian couples—usually but not always make their

retirement plans interdependently.

– The greater the satisfaction in the relationship, the more likely

the couple are to make their retirement plans together

• In married couples,

– husbands more often than wives tend to be in control of the

plans

– although control was also related to the partner’s workload and

income level

Adjustment to Retirement

• Older adults who are best adjusted to retirement are

highly involved in a variety of activities.

• The group most satisfied with retirement maintained

leisure and other non-work-related activities as sources

of life satisfaction or replaced work with more satisfying

activities.

– They retired at a typical retirement age, had a wealth of

resources to compensate for loss of work; they were married, in

good health, and of high SES (Pinquart and Schindler, 2007)

Adjustment to Retirement (cont’d)

• The second retiree group retired at a later age and

tended to be female.

• The majority of the third group retired at a younger age

and tended to be male..

• The second and third groups were not as satisfied with

retirement; they were in poorer health, less likely to be

married, and lower in socioeconomic status than the first

group.

• The third retiree group had a spotty employment record;

retirement per se didn’t change these people’s lives in

major ways.

Adjustment to Retirement (cont’d)

• Adjustment of older retirees may be affected by their

pre-retirement work identities

– Upscale professional workers continued to be well-adjusted and

had high self-esteem

– They considered themselves retired professors or retired

doctors or retired lawyers

• Hourly wage earners and other blue collar workers had

lower self-esteem and were more likely to think of

themselves as simply a retired person.

• The following factors made adjustment to retirement

difficult:

– a lengthy attachment to work

– lack of control over the transition to retirement

– worrying and lack of self-confidence

Leisure Activities and Retirement

• Engaging in leisure activities is essential for retirees’

physical and psychological health.

• Joint leisure activities contribute to satisfaction of marital

and other intimate partners and to family well-being.

• Contributing to civic activities or volunteering to assist in

hospitals enhances retirees’ self-esteem and fosters

feelings of self-efficacy.

• If health remains good, leisure activities carry over from

working days and may ease transition to retirement.

– Physical aspects of aging and the death of companions with

whom the retiree had shared leisure activities can force changes

in choice of activities and diminish satisfaction.

Successful Aging

Successful Aging

• Americans in their 70s report being generally satisfied

with their lives.

• Many older people are robust.

– According to a national poll of some 1,600 adults by the Los

Angeles Times, 75% of older people say they feel younger than

their years (Stewart & Armet, 2000)

• Definitions of successful aging

–

–

–

–

Physical activity, social contacts, self-rated good health

The absence of cognitive impairment and depression

Not smoking

The absence of disabilities and chronic diseases such as

arthritis and diabetes

– Another definition includes high cognitive functioning and high

social networking

Selective Optimization with Compensation

• Selective optimization with compensation

– Older people manage to maximize their gains while minimizing

their losses

• Successful agers

– form emotional goals that bring them satisfaction

– no longer compete in arenas better left to younger people, such

as certain athletic or business activities

– tend to be optimistic

– often challenge themselves by taking up new pursuits such as

painting