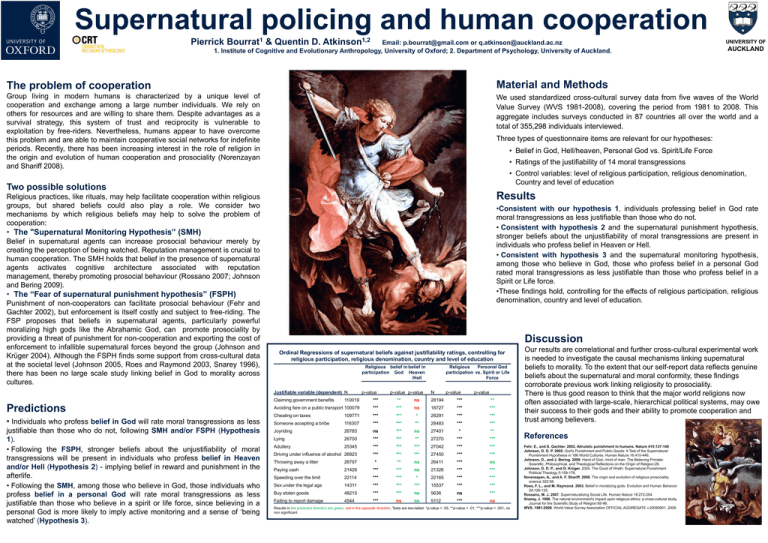

Supernatural policing and human cooperation

Pierrick Bourrat1 & Quentin D. Atkinson1,2

Email: p.bourrat@gmail.com or q.atkinson@auckland.ac.nz

1. Institute of Cognitive and Evolutionary Anthropology, University of Oxford; 2. Department of Psychology, University of Auckland.

UNIVERSITY OF

AUCKLAND

The problem of cooperation

Material and Methods

Group living in modern humans is characterized by a unique level of

cooperation and exchange among a large number individuals. We rely on

others for resources and are willing to share them. Despite advantages as a

survival strategy, this system of trust and reciprocity is vulnerable to

exploitation by free-riders. Nevertheless, humans appear to have overcome

this problem and are able to maintain cooperative social networks for indefinite

periods. Recently, there has been increasing interest in the role of religion in

the origin and evolution of human cooperation and prosociality (Norenzayan

and Shariff 2008).

We used standardized cross-cultural survey data from five waves of the World

Value Survey (WVS 1981-2008), covering the period from 1981 to 2008. This

aggregate includes surveys conducted in 87 countries all over the world and a

total of 355,298 individuals interviewed.

Three types of questionnaire items are relevant for our hypotheses:

• Belief in God, Hell/heaven, Personal God vs. Spirit/Life Force

• Ratings of the justifiability of 14 moral transgressions

• Control variables: level of religious participation, religious denomination,

Country and level of education

Two possible solutions

Results

Religious practices, like rituals, may help facilitate cooperation within religious

groups, but shared beliefs could also play a role. We consider two

mechanisms by which religious beliefs may help to solve the problem of

cooperation:

•Consistent with our hypothesis 1, individuals professing belief in God rate

moral transgressions as less justifiable than those who do not.

• Consistent with hypothesis 2 and the supernatural punishment hypothesis,

stronger beliefs about the unjustifiability of moral transgressions are present in

individuals who profess belief in Heaven or Hell.

• Consistent with hypothesis 3 and the supernatural monitoring hypothesis,

among those who believe in God, those who profess belief in a personal God

rated moral transgressions as less justifiable than those who profess belief in a

Spirit or Life force.

•These findings hold, controlling for the effects of religious participation, religious

denomination, country and level of education.

• The "Supernatural Monitoring Hypothesis” (SMH)

Belief in supernatural agents can increase prosocial behaviour merely by

creating the perception of being watched. Reputation management is crucial to

human cooperation. The SMH holds that belief in the presence of supernatural

agents activates cognitive architecture associated with reputation

management, thereby promoting prosocial behaviour (Rossano 2007; Johnson

and Bering 2009).

• The “Fear of supernatural punishment hypothesis” (FSPH)

Punishment of non-cooperators can facilitate prosocial behaviour (Fehr and

Gachter 2002), but enforcement is itself costly and subject to free-riding. The

FSP proposes that beliefs in supernatural agents, particularly powerful

moralizing high gods like the Abrahamic God, can promote prosociality by

providing a threat of punishment for non-cooperation and exporting the cost of

enforcement to infallible supernatural forces beyond the group (Johnson and

Krüger 2004). Although the FSPH finds some support from cross-cultural data

at the societal level (Johnson 2005, Roes and Raymond 2003, Snarey 1996),

there has been no large scale study linking belief in God to morality across

cultures.

Discussion

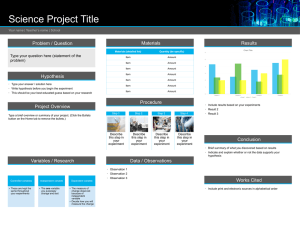

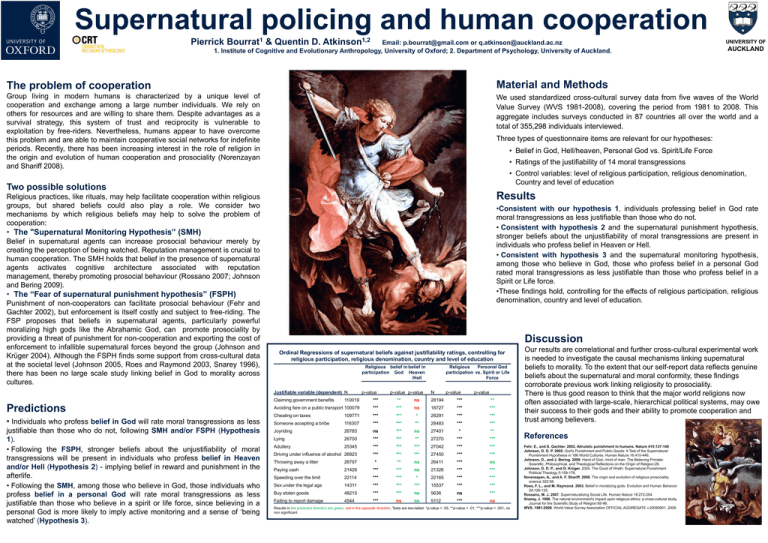

Ordinal Regressions of supernatural beliefs against justifiability ratings, controlling for

religious participation, religious denomination, country and level of education

Religious belief in belief in

participation God Heaven

/Hell

Justifiable variable (dependent) N

Claiming government benefits

Predictions

• Individuals who profess belief in God will rate moral transgressions as less

justifiable than those who do not, following SMH and/or FSPH (Hypothesis

1).

• Following the FSPH, stronger beliefs about the unjustifiability of moral

transgressions will be present in individuals who profess belief in Heaven

and/or Hell (Hypothesis 2) - implying belief in reward and punishment in the

afterlife.

• Following the SMH, among those who believe in God, those individuals who

profess belief in a personal God will rate moral transgressions as less

justifiable than those who believe in a spirit or life force, since believing in a

personal God is more likely to imply active monitoring and a sense of ‘being

watched’ (Hypothesis 3).

p-value

p-value p-value

Religious

Personal God

participation vs. Spirit or Life

Force

N

p-value

p-value

110019

***

**

ns

28194

***

**

Avoiding fare on a public transport 100079

***

***

ns

18727

***

***

Cheating on taxes

109771

***

***

*

28291

***

***

Someone accepting a bribe

116307

***

***

**

28483

***

***

Joyriding

26785

ns

***

ns

27401

*

**

Lying

26700

***

***

**

27270

***

***

Adutlery

25345

***

***

***

27042

***

***

Driving under influence of alcohol 26823

***

***

***

27450

***

***

Throwing away a litter

26797

*

**

ns

26411

***

ns

Paying cash

21426

***

***

ns

21326

***

***

Speeding over the limit

22114

***

***

*

22165

***

***

Sex under the legal age

14311

***

***

***

15537

***

***

Buy stolen goods

48215

***

***

ns

5636

ns

***

Failing to report damage

4544

***

ns

ns

5112

***

ns

Results in the predicted direction are green, red in the opposite direction. Tests are two-tailed. *p-value < .05, **p-value < .01, ***p-value < .001, ns

non significant

Our results are correlational and further cross-cultural experimental work

is needed to investigate the causal mechanisms linking supernatural

beliefs to morality. To the extent that our self-report data reflects genuine

beliefs about the supernatural and moral conformity, these findings

corroborate previous work linking religiosity to prosociality.

There is thus good reason to think that the major world religions now

often associated with large-scale, hierarchical political systems, may owe

their success to their gods and their ability to promote cooperation and

trust among believers.

References

Fehr, E., and S. Gachter. 2002. Altruistic punishment in humans. Nature 415:137-140

Johnson, D. D. P. 2005. God's Punishment and Public Goods: A Test of the Supernatural

Punishment Hypothesis in 186 World Cultures. Human Nature 16:410-446.

Johnson, D., and J. Bering. 2009. Hand of God, mind of man. The Believing Primate:

Scientific, Philosophical, and Theological Reflections on the Origin of Religion:26.

Johnson, D. D. P., and O. Krüger. 2004. The Good of Wrath: Supernatural Punishment.

Political Theology 5:159-176.

Norenzayan, A., and A. F. Shariff. 2008. The origin and evolution of religious prosociality.

science 322:58.

Roes, F. L., and M. Raymond. 2003. Belief in moralizing gods. Evolution and Human Behavior

24:126-135.

Rossano, M. J. 2007. Supernaturalizing Social Life. Human Nature 18:272-294.

Snarey, J. 1996. The natural environment's impact upon religious ethics: a cross-cultural study.

Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion:85-96.

WVS. 1981-2008. World Value Survey Association OFFICIAL AGGREGATE v.20090901, 2009.