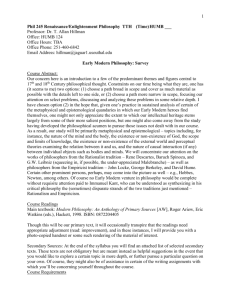

Philosophy 102 Winter 2001

advertisement

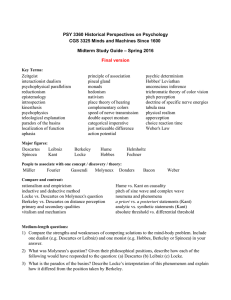

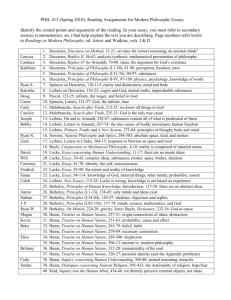

Philosophy 102 Winter, 2001 MODERN PHILOSOPHY Instructor: Allen Wood Lectures: MWF 10-10:50 am Office Hours: M 11:15am -12:15pm, W 11:15-12:00 102O § A: Texts: Descartes Descartes, Meditations on First Philosophy with Selections from the Objections and Replies. ed. J. Cottingham. Cambridge Texts in the History of Philosophy paperback (Revised edition). ISBN 0-521-55818-2 Locke Locke, Essay Concerning Human Understanding. ed. P. Nidditch. Oxford University Press paperback. ISBN 0-19-824-595-5 Leibniz Leibniz, Philosophical Essays. ed. R. Ariew and D. Garber. Hackett paperback. ISBN 0-872-20-062-0 Berkeley Berkeley, A Treatise Concerning the Principles of Human Knowledge. ed. K. Winkler Hackett paperback. ISBN 0-915145-39-1 Hume Hume, Enquiry Concerning Human Understanding. ed. E. Steinberg. Hackett paperback. ISBN 0-915144-16-6 Kant Kant, Critique of Pure Reason. ed. P. Guyer and A. Wood. Cambridge University Press paperback. ISBN 0-521-65729-6. § B: Written Work: 1. A paper (7-10 pages) on Descartes due 2. A paper (7-10 pages), due. § C: Reading Schedule: The following is a schedule according to which you should read the texts (for the first time). It is not a schedule of the lectures, since it finishes well before the quarter. The lectures will therefore soon fall behind the reading schedule, but will nevertheless presuppose that you are keeping up with it. Good philosophical writing needs to be read more than once if it is to be understood. Therefore, it is suggested that you read each assignment at least once according to the following schedule, and then at least once more as we come to it in the lectures. January 8: Descartes, Meditations (1641): Descartes pp. 1-115. January 15: Locke, Essay (1690): Locke, pp. 43-56, 104-132, 140-143, 233-237, 525-573, 609-639, 685-688. January 22: Leibniz, Primary Truths (1686?), Discourse on Metaphysics (1686), New Essays (1703- 1 1705), Monadology (1714): Leibniz, pp. 30-69, 213-225, 291-306. January 29: Berkeley, Principles (1710), pp. 1-92. February 5: Hume, Enquiry (1748), pp. 1-114. February 12: Kant, Critique of Pure Reason (A: 1781, B: 1787), pp. 99-124, 136-152, 172-192, 204231, 245-266. February 19: Kant, pp. 295-300, 304-305, 316-317, 326-329, 411-425, 460-495, 524-550, 563-575, 672-684. § D: Suggested Paper Topics: The following suggestions are aimed at helping you focus your thinking on a paper topic. You do not necessarily need to cover every aspect of the suggested topic (in some cases it would be very unwise to try to do this). Your paper will be graded in part on the judgment you show in making use of the suggested topic to produce an interesting, coherent and self-contained paper. In order to make it easier to provide you with comments on your work, please number your own pages. Paper #1: Descartes 1. Examine the arguments in the first Meditation through which Descartes tries to call all his previous beliefs into doubt. Are the arguments successful in achieving the aim of the Mediations in rendering all beliefs doubtful? 2. Critically discuss Descartes’ proof for his own existence in the second Meditation. What does the argument try to show, and how does Descartes mean to use it in the Meditations? Is it successful? 3. Choose one of Descartes’ two arguments for God’s existence in the Mediations and critically discuss it. 4. Discuss Arnauld’s objection that Descartes argues in a circle when he appeals to God’s veracity in support of the claim that everything we clearly and distinctly perceive is true. Does Descartes provide an adequate reply to the objection? 5. Critically discuss Descartes’ argument in the second Meditation that thinking belongs to his essence and his argument in the sixth Meditation that the mind and the body are really distinct. How do the two arguments relate to each other? Paper #2: 1. Write a paper in which you compare and critically discuss Locke’s and Leibniz’s views on the question whether we have innate ideas and innate knowledge. 2. Consider Locke’s account of the origin of our idea of causal power in light of Hume’s objections to it. Could a defender of Locke’s account give an adequate reply to these objections? 3. Compare Locke’s and Berkeley’s views on the question whether we can form abstract ideas and try to decide which of them is right. 4. Leibniz says that, according to his system of pre-established harmony, "bodies act as if there were no souls (though this is impossible); and souls act as if there were no bodies; and both act as if each influenced 2 the other" (Monadology, Section 81). Explain the meaning of each part of this claim and give Leibniz's reasons for it. 5. Leibniz holds that the complete individual notion of any substance contains everything that is true about that substance (Discourse on Metaphysics, Section 13. To this doctrine Arnauld objected that it makes all truths necessary and abolishes contingency. Does Leibniz have an adequate reply to that objection? 6. Choose one of Berkeley’s arguments that the very concept of material substance involves a contradiction and critically discuss it. 7. Hume declares: “It is universally allowed that matter, in all its operations, is actuated by a necessary force, and that every natural effect is so precisely determined by the energy of its cause that no other effect, in such particular circumstances, could possibly have resulted from it” (Enquiry, VIII, 1). Explain how Hume proposes to render this remark consistent with his earlier skeptical doubts about our knowledge of future matters of fact and about the origin of the idea of causal power or necessary connection. Are Hume’s views on this point in fact self-consistent? 8. What is Kant’s reply to Hume’s skepticism concerning the principle of causality? Is it a convincing reply? 9. What does Kant mean by ‘synthetic a priori’ cognition? Why does Kant think we have such cognition, and why does he think it is important that we do? 10. What does Kant mean by the assertion that we know empirical objects only as they appear but not as they are in themselves? Is Kant’s transcendental idealism essentially the same view as Berkeley’s idealism? Where (if at all) do the two views differ? § E: Late Papers: Never ask for an 'extension' of a paper deadline! (The very word is hateful to me.). Papers that come in after they are due are late (that’s the right word). Late papers may sometimes be accepted for credit, but subject to the following rules: 1. Because a late paper has had the benefit of more time to work on it, late papers will be graded by higher standards than papers turned in on time. During the first two weeks of lateness no mechanical rule about this is possible, but in grading a late paper we will keep in mind how late it is. 2. If a paper is turned in more than two weeks after it is due, the highest grade it can receive is C. 3. Nothing whatever that is turned in after the end of the examination period will receive credit. ( It won’t even be read.) 4. Anyone needing an Incomplete must request one by the last day of classes. Come to me early about problems. If you face some major personal difficulty that runs you afoul the above rules, discuss it with your teaching assistant privately, at office hours, as soon as you know about it. Do not delay such a discussion in order to avoid embarrassment. In these matters, the consequences of delay can often be worse than any amount of embarrassment. 3