“Plot” the Plot

advertisement

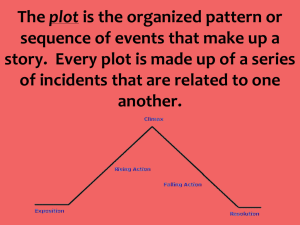

“Plot” the Plot Freytag’s Pyramid: A visual aid for describing narrative structure, seeing the effect of conflict, and charting the traditional ‘5 act’ story-line. Why use the pyramid? • The visual is meant to represent the normal ‘feeling’ of tension (rising or falling) or lack of tension in customary or traditional plotlines. • It is not studied and applied because ALL stories have a 5 act plot structure. • We use it in literary criticism because many if not most authors do follow the rules. It is what the reader expects. Its what the author knows the reader expects. However, this also allows the author to choose to alter it slightly or dramatically to achieve disorientation, ironic twists, suspense, and more. Major changes to the traditional plot startle, confound, tantalize and (always a risk) even ‘turn off’ readers. What are the 5 parts? • Although we could break it down further, we recognize 5 basic parts of the traditional plot. • • • • • The The The The The Exposition Rising Action Climax Falling Action Dénoument • The five parts are depicted as a pyramidal chart, with the spike of the pyramid indicating the level of ‘excitement’ or ‘tension’ known as the Conflict. What does it look like? This is the basic 5 part structure. The Exposition • The Exposition: This is the introduction to the story. Here is often found all of the information the reader needs to know before the real story begins. Characters, Setting (time and place), and events outside the plot take up a great deal of the ‘action’ (or inaction) of this part. • In short stories, this part can be quite short or even missing. The question to ask is “What information has been left out that the reader might want or miss? • In longer works, this part can be quite long, and may make readers think that the work ‘starts off slowly.’ The question to ask is “What is so important about this information that the writer spent so much time on it?” You can imagine that this question is doubly important if a short story has a long exposition! The Rising Action • Sooner or later something happens to set the story in motion. Tension is caused by an event or character action. A conflict is created. The first big ‘plot complication’ has occurred! • We traditionally call this the ‘inciting event’ in ‘Freytag-speech’ and this is visually the place where the spike starts upwards. • After this moment, there will be a number of other plot complications (or complicating actions). The more of them there are, the longer this part becomes, the more tangled the plot becomes, the deeper the tension, the more pronounced the conflict… you get the idea. The Climax • This is also called the Crisis • An author’s worth is often gauged by the impact of their climax-moments. The climax of a story is often accompanied by great revelations, catastrophic events, blissful reunions (although marriages are often later in the happily ever after sequence - just wait). • In essence, a great reversal of fortune is expected (good to bad, bad to good) or a fulfillment of goals and expectations established in the rising action. The Falling Action • Traditionally, the climax does not end the story. Rather, a series of repercussions of the central crisis occur as the plot ‘untangles’ itself. • Do not think that there is no more tension left at this point; the pyramid is still ‘up in the air,’ but the reader has a sense that things are winding down, not building. • At the end of the falling action is a step often called the ‘Resolution’ - at this point the story has come to an event or situation that puts the conflict to rest. • In a short story, the amount of story telling between the climax and the resolution can be quite short. • Long or short, the question to be asked is ‘How does this resolution (or lack of it) make me feel, or what does it make me think?’ Or perhaps ‘How has the author given (or withheld from) me (and his characters) closure?’ The Dénoument • Neat word, huh? It is pronounced ‘Day-Noo-Mah’ and it is French. And yes, it basically means ending. It is a tying up of loose ends. • At this point, any remaining secrets, questions or mysteries which remain after the resolution are solved by the characters or explained by the author. Sometimes the author leaves us to think about the theme or future possibilities for the characters. • As you can imagine, this step can be short, implicit, or completely contained by the resolution. Indeed, in many versions of Freytag’s pyramid, the ‘resolution’ is the title of the whole last step, recognizing the tendency to leave out the ‘And they lived happily ever after’ statement as superfluous. What are we left with? • With the resolution and inciting event included, the pyramid now looks like: Inciting Event Resolution • A Simple Example: Cinderella Exposition: Once upon a time there was a girl. Mom was dead. Dad remarried. Dad died. Girl abused by stepmother and stepsisters. How sad. • Inciting Event: Then, one day the prince of the land decided to host a ball (perhaps seeking a wife?) • Rising Action (Complicating Events): An invitation came to the house… Cinderella could not go, she had no dress… Fairy Godmother… Nifty dress and pumps… Must be home by midnight… • Climax: Cinderella goes to the ball, the prince falls in love, but she must flee (the glass slipper left behind). • Falling Action: The Prince is in love, but does not know who. Travels the kingdom seeking the mystery girl (using the ‘footgear test’ method). • Resolution: Cinderella is called and the slipper fits! • Dénoument: They get married and live happily ever after. See? Now you try… You are not done! • About now, you are feeling pretty good about Freytag and his delightful pyramid. If you plug in a children’s fairy tale, it works every time. However, fairy tales are, by their very nature, traditional. • Now take a short story you have read or a novel you are familiar with - try to divide it into a ‘5 act story line’. If it doesn’t work out easily, you are not necessarily wrong. This is especially the case if you have always thought of the story as having a unique plot. What does it mean? • Your job, as a literary critic, is to compare the traditional structure of a plot to the story-line you are reading. Then ask the questions that come to mind: ? Why did the author choose to follow the standard plot-line? What did he or she get from being ‘familiar’ (structurally speaking) ? Or, why did the author break out of the traditional structure altogether? ? Or, What did the author accomplish by following the standard plot structure and then change it up? ? And/Or, How did the author’s use (or abuse) of the standard plot-line help me understand the story or predict the outcome, or did it keep me guessing and in suspense? Did the author use his or her knowledge of plot to mislead me? Confuse me? Tantalize me?